- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When Amelia Earhart disappeared on July 2, 1937, she was flying the longest leg of her around-the-world flight and was only days away from completing her journey. Her plane was never found, and for more than sixty years rumors have persisted about what happened to her.

Now, with the recent discovery of long-lost radio messages from Earhart's final flight, we can say with confidence that she ran out of gas just short of her destination of Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean. From the beginning of her flight, a series of tragic circumstances all but doomed her and her navigator, Fred Noonan.

Authors Elgen M. and Marie K. Long spent more than twenty-five years researching the mystery surrounding Earhart's final flight before finally determining what happened. They traveled over one hundred thousand miles to interview more than one hundred people who knew some part of the Earhart story. They draw on authoritative sources to take us inside the cockpit of the Electra plane that Earhart flew and recreate the final flight itself. Because Elgen Long began his own flying career not long after Earhart's disappearance, he can describe the equipment and conditions of the time with a vivid first-hand accuracy. As a result, this book brings to life the primitive conditions under which Earhart flew, in an era before radar, with unreliable communications, grass landing strips, and poorly mapped islands.

Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved does more than just answer the question, What happened to Amelia Earhart? It reminds us how daring early aviators such as Earhart were as they risked their lives to push the technology of the day to its limits -- and beyond.

Now, with the recent discovery of long-lost radio messages from Earhart's final flight, we can say with confidence that she ran out of gas just short of her destination of Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean. From the beginning of her flight, a series of tragic circumstances all but doomed her and her navigator, Fred Noonan.

Authors Elgen M. and Marie K. Long spent more than twenty-five years researching the mystery surrounding Earhart's final flight before finally determining what happened. They traveled over one hundred thousand miles to interview more than one hundred people who knew some part of the Earhart story. They draw on authoritative sources to take us inside the cockpit of the Electra plane that Earhart flew and recreate the final flight itself. Because Elgen Long began his own flying career not long after Earhart's disappearance, he can describe the equipment and conditions of the time with a vivid first-hand accuracy. As a result, this book brings to life the primitive conditions under which Earhart flew, in an era before radar, with unreliable communications, grass landing strips, and poorly mapped islands.

Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved does more than just answer the question, What happened to Amelia Earhart? It reminds us how daring early aviators such as Earhart were as they risked their lives to push the technology of the day to its limits -- and beyond.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Amelia Earhart by Marie K. Long,Elgen M. Long in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 : TRAGEDY NEAR HOWLAND ISLAND

FRIDAY morning, July 2, 1937, Lae, New Guinea. It was not yet ten o’clock, but the tropical sun already beat down unmercifully on the twin-engine Lockheed Electra. Inside the closed cockpit, Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, could feel the heat build as they taxied away from the Guinea Airways hangar.

The heavily loaded plane lumbered slowly across the grassy airfield toward the far northwest corner. Soon they would take off southeastward toward the shoreline, to take advantage of a light breeze blowing off the water. When they reached the jungle growth at the end of the field, Earhart swung the plane around to line up with the runway for departure. Only 3,000 feet long, the grass runway ended abruptly where a bluff dropped off to meet the shark-infested waters of the Huon Gulf.

Earhart was preparing to take off with the heaviest load of fuel she had ever carried. She and Noonan had flown 20,000 miles in the previous six weeks. Now only 7,000 miles of Pacific Ocean separated them from their starting point in California. The Electra, nearly 50 percent overloaded, was weighted to capacity with 1,100 gallons of fuel for the 18-hour flight to the next stop, Howland Island. Less than a mile wide, two miles long, and twenty feet high, their destination was just a speck of land that lay nearly isolated in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It was truly a pioneering flight over a route never flown before, and they would be the first to land at the tiny island’s new airfield. Two more firsts for the famous thirty-nine-year-old aviator, who upon reaching California would become the first woman pilot to have flown around the world.

Fred Noonan, at age forty-four, was famous in his own right. As chief navigator for Pan American Airways he had navigated the Pan American Clippers on all their survey flights across the Pacific. Now, both he and his pilot knew that the grossly overloaded takeoff would put their lives at great risk.

Fred watched closely as Amelia ran up each engine and checked it for proper operation. She gave the instruments a final scan, and they were ready to go. The moment of truth had arrived.

Amelia advanced the engine throttles full forward and released the brakes. The roaring, straining airplane slowly accelerated as it began its ponderous takeoff roll. Her feet were busy on the rudder pedals, moving them left, right, back, and forward to keep the plane going straight down the runway. They passed the smoke bomb that marked the halfway point to the shoreline. The tail wheel was already off the ground; they were going over 60 mph. There was no stopping the heavy plane now; it was fly or die, and the bluff at the end of the runway was coming up fast. Amelia applied back pressure on the control wheel to lift off the ground. The force required was lighter than she expected, and the plane over-rotated slightly as the wheels left the runway. She relaxed some of the pressure, allowing the nose-high attitude to decrease slightly.

They were off the ground, but their airspeed was too slow for optimum climb. When they were beyond the edge of the bluff, Amelia let the plane sink slowly until it was only five or six feet above the water. She signaled Fred to retract the landing gear, and the electric motor began cranking the wheels up into the nacelles to reduce drag. The seven seconds required to retract the landing gear seemed more like seven minutes as the engines struggled at full power to increase the airspeed.

After several seconds, Amelia could tell that she needed less back pressure on the control wheel to hold the craft level. This signaled that the battle between the engines and the drag of the airplane was slowly being won by the engines. The airspeed was increasing; they were going to make it. When the indicated airspeed increased to optimum climb speed, Amelia let the plane rise from its dangerous position just over the water. After they were safely a couple hundred feet in the air, she gently turned the plane to a compass heading of 073 degrees, direct for Howland Island. She reduced the engines to climb power and quickly scanned the engine gauges to check that everything was normal. They breathed easier as the plane slowly rose to the recommended initial cruising altitude of 4,000 feet.

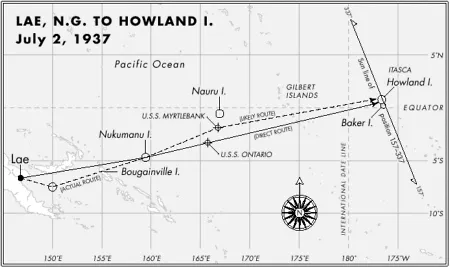

Fred wrote down their takeoff time from Lae as 0000 Greenwich civil time (GCT), July 2, 1937. Having calculated that the flight to Howland Island would take 18 hours, they had to time their arrival to occur at daylight the following morning. Fred would need the stars to be visible for celestial navigation until just before they reached the island.

Amelia had arranged for a message to be sent from Lae to notify the Coast Guard cutter Itasca at Howland Island of her departure. The 250-foot Lake class cutter was waiting just off the island to provide communications, radio direction-finding, weather observations, and ground servicing for her flight. The captain of the Itasca was to notify all other stations, including the U.S. Navy auxiliary tug Ontario. The Ontario was positioned approximately halfway between Lae and Howland Island, in order to provide weather reports and transmit radio homing signals for Earhart.

Harry Balfour, the Guinea Airways radio operator at Lae, was receiving new wind forecasts for Earhart’s flight just as she was taking off. The messages indicated that the headwinds to Howland Island would be much stronger than reported earlier, when they had expected only a 15 mph headwind. Fred had subtracted this headwind from the 157 mph optimum true airspeed to calculate a 142 mph ground speed. At 142 mph it would take them 18 hours to fly the 2,556 statute miles to Howland Island.

Earhart’s radio schedule with Lae called for her to transmit her messages at 18 minutes past each hour, and to listen for Lae to transmit its messages at 20 minutes after the hour. Balfour attempted to report the stronger headwinds to Earhart by radio at 10:20, 11:20, and 12:20 local time, but she never acknowledged having heard him. In addition, for more than 4 hours after she departed from Lae, local interference prevented signals sent by the plane from being intelligible until 0418 GCT.

At 0418 GCT (2:18 P.M. local time), Balfour finally received a radio transmission from Earhart using the daytime frequency of 6210 kilocycles. She reported: “HEIGHT 7,000 FEET SPEED 140 KNOTS” and some remark concerning “LAE” then “EVERYTHING OKAY.”

At four hours and eighteen minutes into the flight they were already experiencing stronger headwinds than anticipated. The increased winds had made them recalculate their optimum speed. Amelia reported the change to 140 knots (161 mph) in her message.

Maintaining the correct airspeed was important, but Earhart also had to fly at the correct altitude for optimum fuel efficiency. As the engines burned fuel, the plane’s weight would decrease and the optimum altitude would increase. At any given aircraft weight there is a specific altitude for best fuel economy. The higher temperatures common in the tropics reduce the density of the air. Above the optimum altitude the temperature’s effect on air density is equivalent to approximately a 2,000-foot increase in altitude and a corresponding increase in fuel consumption. The Electra would lose fuel efficiency below the optimum altitude but not nearly as rapidly as when flying above it. For maximum efficiency in the tropics, the Electra had to be flown approximately 2,000 feet below the recommended pressure altitude.

Balfour heard the next report from Earhart in Lae one hour and one minute later, at 0519 GCT. She reported: “HEIGHT 10,000 FEET—POSITION 150.7 EAST, 7.3 SOUTH—CUMULUS CLOUDS—EVERYTHING OKAY.”

Perhaps the cumulus clouds or the 9,000-foot mountains of Bougainville Island had forced them to the very uneconomical altitude of 10,000 feet. The worst had happened; they were flying at a density altitude close to 12,000 feet. The gross weight of the plane at this point would require them to burn an unconscionable amount of extra fuel to reach and cruise at that altitude. The resulting inefficiency could cost them a significant portion of their fuel reserve.

The position indicated by the reported geographical coordinates, longitude 150.7 east and latitude 7.3 south, is less than 220 statute miles from Lae and well over 450 miles from where the Electra would have been at 0519 GCT. Since it was standard practice for ships at sea to give their position at noon every day, it’s possible that this was their position at twelve noon local time. It definitely was not their position at 0519, when Earhart transmitted the message.

Lae heard nothing from Earhart during her 0618 GCT transmitting schedule, but at 0718 GCT Balfour heard her report clearly on 6210 kilocycles: “POSITION 4.33 SOUTH, 159.7 EAST—HEIGHT 8,000 FEET OVER CUMULUS CLOUDS—WIND 23 KNOTS.”

This position, approximately 850 statute miles from Lae, was right on their planned course to Howland Island. Significantly, the position was just to the west and in sight of Nukumanu Island. Noonan had navigated perfectly so far; they were exactly on course with a positive visual fix. A true airspeed of 161 mph reduced by a 26.5 mph (23-knot) wind would give them a ground speed of 134.5 mph. Again, the geographical position reported is not where they were at the time when the report was received by Harry Balfour in Lae; Earhart would have been at the reported position near Nukumanu Island approximately one hour earlier. Perhaps the activity resulting from sighting Nukumanu explains why Balfour in Lae did not hear from Earhart during her 0618 GCT transmitting schedule. Her signals on 6210 kilocycles were strong before and after 0618, and if she had transmitted, he should have heard her. (The reason why the radio position reports made by Earhart to Lae were not correlated to the time she transmitted them is unknown.)

At Nukumanu Island, Earhart and Noonan were approximately one-third of the way to Howland Island. They had been flying about six and a half hours and had a positive visual fix of their position. They knew their ground speed and the heavy plane’s hourly fuel consumption precisely. None of the news was good. It would be prudent for them to reevaluate the remainder of their flight.

No pilot appreciates strong headwinds that make a flight fall behind schedule, but Earhart was doubly handicapped on fuel. The 26.5 mph headwind required her to fly at 140 knots (161 mph) to obtain maximum range. That was 11 mph faster than the required zero-wind speed of 150 mph. This increased fuel consumption by about 9 percent per hour, but her progress over the ground was also increased by about 9 percent. (For every wind component there is a recommended speed for maximum range. The stronger the headwind, the faster a plane must fly. It may sound incongruous, but consider an extreme situation with a headwind of 155 mph: A plane flying at the no-wind speed of 150 mph would be driven backward. At a speed faster than 155 mph, it will run out of gas much sooner but will be farther along the way when this happens.)

Whether or not Earhart had heard the messages from Lae concerning the increased headwinds, she had already encountered the actual winds. She acknowledged their importance by reporting the 23-knot (26.5 mph) wind at 0718, and significantly she did not then, or ever again, end a message with her earlier sign-off, “Everything okay.”

So far, Earhart had maintained the optimum airspeed, but if the excessive fuel consumption continued they would arrive at Howland Island with little if any fuel remaining. The situation was very serious. If they were going to return to Lae, they had to turn about before they were beyond the point of safe return.

A number of factors had to be weighed as Earhart made her decision to continue or return. The badly overloaded takeoff from Lae was punishing to the plane. The margin of safety had been so minimal that she would not want to expose them to it again unnecessarily. Even with a headwind it had required every bit of engine power that the plane could produce with 100-octane fuel, and there was no more 100-octane available at Lae. Earhart could not responsibly attempt another takeoff using only the 87-octane fuel that was available. A major delay would be caused by having to transport more 100-octane fuel to Lae.

Pilot and navigator had to weigh the hazards of continuing against the hazards in returning. It would be dark in an hour or two, and the 24-day-old waning moon would not rise until after one o’clock in the morning. There were no high peaks between Nukumanu Island and Howland Island, but there were the 9,000-foot peaks back on Bougainville Island between them and Lae. With their excess weight, if they lost an engine they might not be able to maintain altitude to clear the mountains. Lae was surrounded by mountains over 12,000 feet high on three sides, and near the airfield the terrain was over a thousand feet high. There were no landing or obstruction lights, so they could not land safely until daylight. Sunrise at Lae would be about 2020 GCT, nearly an hour and a half after they were due to arrive at Howland Island. No high terrain lay ahead, and if the weather cooperated they should be able to keep the plane operating optimally for the rest of the trip. They had now burned off enough fuel to be flying at comfortable weights.

As Earhart continued toward Howland Island, she descended to 8,000 feet to get closer to the optimum altitude. It was still too high, but as they would not have to climb back up to it later, it was a reasonable choice. With better fuel economy and a tailwind replacing a headwind, they could safely return to Lae after 10 hours. They could not land back there before 2000 GCT anyway, so she could delay her decision until 1000 GCT.

The sun had set about an hour before. It was dark as the Electra continued eastward toward Howland Island. On his map, Noonan could measure that at 0810 GCT they would be about 200 miles west of the Navy guard ship Ontario, which for over a week had been keeping near the midpoint position waiting for Earhart to pass.

The coal-burning Navy auxiliary tug was not equipped with the high-frequency radio equipment needed to receive Earhart’s transmissions on 3105 or 6210 kilocycles. The low-frequency radios on the ship prevented it from communicating with its base in American Samoa except at night. Earhart had requested by cablegram before takeoff that the Ontario send a series of Morse code “N’s” at 10 minutes after each hour on 400 kilocycles. She wanted to be able to take radio bearings on the ship with her radio direction-finder as they flew by. If she listened to her Bendix radio receiver for the “N’s” at 10 minutes after the hour, she heard nothing.

At 0815 GCT, Earhart was scheduled to transmit a quarter-after-the-hour report on the nighttime frequency of 3105 kilocycles to the Coast Guard cutter Itasca, waiting just offshore at Howland Island. Neither the Itasca nor Balfour back at Lae heard anything. This was not surprising, as both were over a thousand miles away, and her Western Electric transmitter was rated at only 50 watts.

At 0910 GCT she may have listened again for “N’s” on 400 kilocycles, because at a ground speed of 134.5 mph she would be passing by the ship just before 0940 GCT. She must have been disappointed when she did not receive any of the scheduled signals from the Ontario. She had no way of knowing that her departure message from Lae had been delayed. The Ontario never logged sending “N’s” on 400, and soon after 1500 GCT set course...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Colophon

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- Appendix

- Flight Log for Earhart’s Around-the-World-Flight

- The Electra’s Fuel Consumption

- Notes

- Sources

- Acknowledgments

- Index