![]()

1

The Apprentice

1942 (age 14)

It always started with a low moan that rapidly turned into a wail: ‘a wailing banshee’ our Prime Minister Winston Churchill used to call the air-raid siren; to us East Enders, she was ‘Moaning Minnie’.

The bombers were returning for another go.

‘Pull up . . . pull up!’ Uncle Tom shouted. ‘Go and find a shelter, Stan, go on . . . hurry up now, boy.’

I jumped down and ran along the row of houses, looking for one with a white ‘S’ painted on the wall, which signified there was a shelter for anyone caught in a raid. I found one a little way down the road and knocked hard on the door.

It was opened by an elderly lady with no teeth and a tea cosy on her head. All of a sudden my breath was taken away by a powerful waft of mothballs. I hated that smell and, to make matters worse, it was clashing sickeningly with ‘Evening in Paris’, a scent every woman wore because, I suppose, it was the only one around at the time. Both reminded me of great-aunts wearing bright-red lipstick with whiskers on their chins, trying to kiss me under the mistletoe at Christmas, but this heady mixture made me feel slightly queasy.

‘Cor blimey, you’re done up for a Monday, ain’tcha?’ she said, giving me a toothless grin.

‘In you come, love, quickly now, they’ll be ’ere soon.’ She opened the door wider, engulfing me again. Honestly, it was a good job I’d left my gas mask at home otherwise I would’ve been seriously tempted to put it on. She pointed into the hallway. I must have been staring at the tea cosy, which was knitted in claret and blue, the colours of West Ham United Football Club. It was securely pulled down on her head, and it seemed to have been strategically placed so her ears peeked out of the spout and handle holes.

Her hand automatically shot up to touch it. ‘Oh, don’t take any notice of this, son, it’s me lucky ’at, makes me feel safe. Forget I’ve got it on these days, as I ’ardly take it off,’ she chuckled. ‘And me teef . . . in case you’re wondering, are in a tin can under the stairs. You see, I always take ’em out when there’s a raid on, as I’ve ’eard . . .’ she leant forward, lowering her voice to a whisper, ‘. . . that if you get ’it, the force of the blast can blow ’em out of your mouth and kill the poor bugger sitting opposite.’ She said it in a way that told me she’d only heard this bit of gossip in the last few days and was excited to be forwarding her new-found knowledge onto me.

I wanted to tell her that if she was hit then having her teeth in or out really wouldn’t make a blind bit of difference – but I didn’t. I swear to you, her logic was completely lost on me.

‘Go on now, off you go, son, get down in the shelter.’

‘That’s very kind, ma’am, but it’s not just me . . . it’s them too,’ I said, pointing out into the street.

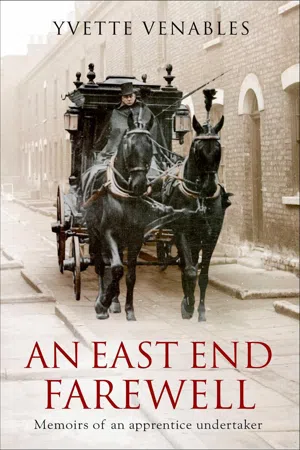

She peered around the door and gasped, ‘Oh, my gawd!’ She was staring at six magnificent jet-black Friesian horses, brushed so they shone in the summer sunshine; each pair pulled a carriage driven by a coachman, the first bearing the coffin, followed by two carrying the twelve mourners. ‘Oh, my giddy aunt, you’re a bleedin’ undertaker. Why didn’t ya say so!’ she laughed. ‘Go and fetch ’em in . . . but ’urry now.’

With that I ran back and we started unloading the mourners. It was time-consuming, as most of them were elderly men and women and negotiating the carriage steps was tricky.

The sirens by then were screaming, and we could hear the distant drone of the bombers getting closer. ‘Please, hurry up,’ I heard myself saying. ‘We haven’t got much time.’

One of the gentlemen mourners turned to me, his face puce with anger, ‘Bloody Jerries will ’ave to wait, son. They won’t even let us bury our dead in peace. Dirty bastards!’ he shouted, looking up at the sky as if they could hear him.

At last they were all off and heading towards the shelter. As the final mourner entered I started to follow when a booming voice came from behind me.

‘Where the hell do you think you’re going, boy?’

It was Uncle Tom, standing by the carriages, immaculate as always in his morning suit and top hat. He had such a commanding presence. He was around 5' 10" tall and very well-built. His head was virtually shaved, although there was a trace of white hair showing through. Everyone in those days had a moustache (not the women, of course!), but his was fabulous. A brush moustache they used to call them, and his was snow white. I always admired it.

‘Er . . . I’m going into the shelter, Uncle . . . bombers are nearly here,’ I said, feebly pointing upwards. I don’t know why he was asking and not just following.

‘Exactly!’ he bellowed.

Without a word of a lie, when he shouted you stood to attention; when it turned into a bellow you automatically cowed.

‘They’re coming, so you need to be here,’ he said, pointing to the spot at the head of the cortège. I ran towards him feeling like one of those puppies who know they’re going to be beaten, looking all hunched up ready for the blow.

‘For heaven’s sake, Stan, what’s wrong with you, boy, you look like Uriah Heep. Straighten up. I’m not going to bloody hit you. Come on, now, stand here at their heads and don’t you dare move! And for Christ’s sake, don’t let the horses see you’re scared, ’cos they smell fear, you know.’ And with that he marched off, disappearing into the house and leaving me alone with horses, carriages and coffin.

It now seems as good a time as any to introduce myself. My name is Stanley Harris, more commonly known as Stan Cribb of CRIBB & SONS, FUNERAL DIRECTORS. It’s 1942, I’m fourteen years old, and I am very proud to tell you that I’m an apprentice undertaker.

I was scared stiff as I stood there, not of the bombers flying overhead but of Uncle Tom. I knew as sure as eggs is eggs he wouldn’t be in the shelter; he’d be lurking behind the tea cosy lady’s lace curtains watching me, studying my every move. I could sense his eyes on me, and I’m deadly serious when I say that put the fear of God into me, not because I thought he would hit me, as he never did, but because of my job. I knew, being the perfectionist he was, one wrong move and I’d be out on my ear. I stood at the head of the cortège, as still as I could, holding onto the reins so tightly my fingernails cut into my palm. I wanted him to be proud of me. He and I knew there would be lots of lace-twitching down the street that day.

I looked around to check the horses; they stood grandly at the head of each carriage, occasionally scraping their hoofs on the ground or shaking their beautiful heads. One had left a pile of steaming dung behind it but it didn’t matter, as I knew it wouldn’t be there for long.

You know what, their calmness never ceased to amaze me, as our stables and garages were so close to the docks that on a good day you could read the names of the ships. That’s where most of the heavy bombings took place, so they’d grown accustomed to the daily racket.

It was amazing how during the war animals and humans adjusted to the most horrible of situations.

Fortunately this raid didn’t last for long. Normally we were bombed during the early evening or night-time, so having a daylight raid was unusual. It was over within half an hour and that glorious sound of the two minute ‘all clear’ siren was heard.

The front door opened and Uncle marched out followed by the mourners. I could hear the tea cosy lady being thanked by everyone.

As they left I heard ‘Cooeee!’ I turned around and there she was, standing waving at me. I wouldn’t have minded if it had been a proper wave but it was one of those silly waves that Oliver Hardy used to do – where he just kept moving his fat fingers up and down in front of his face. Then, and you won’t believe this, she said all coyly, ‘This is what I normally look like.’ She stood there with her tea cosy removed and, I’m not joking, she was smiling at me showing a set of ‘teef’, which would’ve made one of our horses proud.

At that moment it did cross my mind that if they had hit you they definitely would’ve killed you!

I smiled and waved back. ‘Lovely,’ I said, blushing.

Uncle walked towards me grinning. He winked. ‘You’ve got an admirer there, Stan. Perks of the job, son, perks of the job,’ he said out of the corner of his mouth, as he carried on walking to the mourners’ carriage to load everyone back on so we could continue onto the cemetery.

As we pulled away I heard a commotion behind us. Two ladies shot out of their adjoining houses. They moved so fast I imagined they’d built giant catapults in their passages. Huge pieces of elastic attached to the surround of the front door which they sat in whilst the rest of the family hauled them back then launched them out into the road, their legs pumping like pistons to keep upright. Overalls on, hair tied up in headscarves covering the indispensable rollers, both carrying metal buckets and shovels, they shouted at each other and were laughing. They pounced on the heap of dung and, by the expressions on their faces, I don’t believe they could’ve been any happier if they’d found Errol Flynn (at that time he was the world’s favourite handsome swashbuckling actor) lying there waiting for the kiss of life.

I remember thinking to myself, What has the world come to when shovelling up a heap of horse dung could bring so much pleasure? They shared it equally between them then ran back into their houses, no doubt heading towards their small back gardens where it would be quickly dug into their treasured vegetable patches. Then they could really get stuck into some serious gossiping over the garden fence.

Many people had allotments in those days. My dad loved his and spent most of his free time tending it. In fact, when the war started in 1939, due to the shortage of food caused by ships being attacked by enemy submarines, and cargo ships being deployed to carry war materials rather than food, we had an extreme shortage, so this is the reason why the government launched the rationing scheme.

All families were given a ration book, which you registered with your chosen shops. Each time you went in to buy food the items were crossed off the book by the shopkeeper. This made sure that people got an equal amount of food every week, as the government was worried that as food became scarcer, prices would rise and the poorer people would suffer and not be able to afford it. Also there was the risk that the wealthier families would hoard food, leaving it in even shorter supply. But the amount we were allocated was so small you could see why there weren’t any fat people about. All we were allowed per person, per week was: 2oz (50g) butter, 8oz (225g) sugar, 2oz (50g) cheese, 4oz (100g) bacon and ham, 4oz (100g) margarine, 2–3 pints (1200–1800ml) milk, one fresh egg, one packet of dried eggs every 4 weeks, 2oz (50g) tea, meat to the value of one shilling and sixpence, which was about 1lb 3oz (525g), 1lb (450g) jam every two months and only 12oz (350g) sweets every four weeks.

Bread, fruit, vegetables and potatoes weren’t rationed, so we tended to fill ourselves up with those, although fresh fruit was still hard to come by. We only had apples and pears when they were in season and, if we were really lucky, we found an orange in our Christmas stocking. It’s astonishing how we coped with such meagre portions, but somehow we did; in fact, how we survived at all during those days was miraculous in itself. Nobody had even heard of the word obesity back then, let alone be suffering from it.

A ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign was launched and people all over the country were encouraged to use their gardens and every spare piece of land around them to grow food. Tennis courts, golf courses, parks and even the moat around the Tower of London were used to grow as many vegetables as possible. In 1943 the number of allotments had grown from 815,000 to 1,400,000. It was an unbelievable success.

At the end of the day, when we’d returned to the stables, I made us all a cup of tea and sat chatting with the coachmen.

‘I couldn’t believe Uncle Tom left me in charge of the cortège today,’ I said smugly.

Jack, Tommy and Charlie were all highly respected professional coachmen. These men, all in their forties and fifties, had been employed by my grandfather and uncle for most of their working lives. They glanced around at one another, bursting into spontaneous laughter followed by all sorts of insulting comments, which I shan’t repeat.

‘What?’ I said. I was seriously cheesed off.

‘Listen, Stan,’ said Jack, who was the Head Groom. We all looked at him stunned, as he certainly wouldn’t be called ‘a man of words’ – he only spoke when he absolutely had to, and most of the time you were lucky to get a ‘good morning’ and ‘good night’ out of him. He had one of those hangdog faces, with rheumy eyes, you know the type – he looked like he’d never received one bit of good news in his entire life and was permanently on the verge of tears, but believe me he wasn’t; tough as old boots he was.

‘It’s time you ’eard a few home truths. Now, just ’cos you’re related to the boss, doesn’t mean you’re something special, you know. You silly little sod, if the truth be known we left ya ’cos you’d be surplus to requirements if we took a hit.’

As he got off his stool and turned to walk away, he stopped and looked back at me, leant over and put his finger under my chin and gently pushed up. ‘Close your mouth, son, makes you look soft in the ’ead and you don’t need any ’elp on that score! And you’d do well to remember if you plan on staying ’ere, respect’s earned, not bloody inherited.’ And with that he walked off home with Tommy and Charlie close behind in a state of shock at this unexpected speech.

I sat there for ages after they’d gone feeling like an absolute idiot. What a stupid thing to have said. I’d only been an apprentice for a few months and although my dad hadn’t literally said it, I knew for a fact that he wasn’t too keen on me being an undertaker and now I was sitting there thinking perhaps he was right.

It all started in 1881, around 220 years after the first ‘official’ undertakers were recognised. The undertakers in those days were generally builders/carpenters who would be asked to make the coffins, so the natural progression was for them to organise the whole thing. My grandfather, Thomas Cribb, had opened the business with my grandmother, Caroline Susan, more commonly known as Carry. He started out as a coffin-maker for a company called Hannaford’s in Canning Town. After learning the ropes he decided to take the plunge and open a business of his own. They had five children: Tom, George, Fred, Bert and Catherine, who was more commonly known as ‘Kitty’. George, Fred and Bert joined them in the business during the early years, but George and Bert eventually left to pursue other careers, which left Fred – who was born virtually stone deaf – to remain as a coffin-maker. Tom wouldn’t join the family business until 1934. He’d decided to go off and learn the trade in other parts of the country first. My grandfather died in 1925 and the business was run, until the day she died in 1944, by my grandma.

On 4 June 1923 at Trinity Church, Canning Town, their daughter Catherine married Police Constable Alfred John Harris and on 7 November 1928 I was born. Our first family home together was 25 Pulleyns Avenue and in 1930 we moved to 21 Ladysmith Avenue, both in East Ham, where I was later joined by two sisters: Olive in 1931 and Molly in 1940.

Every weekend we would visit our grandma’s flat, which was above the Funeral Directors’ shop at 120 Rathbone Street, Canning Town. When we arrived I would always make a beeline for the yard, not far away in Lansdowne Road, so I could watch the horses being groomed, the carriages polished and the coffins being made. Every time I walked through those large wooden double doors, with the small wicket door built into one side, I thought it was magical.

Over on the left-hand side were the tack room and stables, and at the bottom was the work room, where the wood for the coffins and carriages was stored. When you walked up the stairs to the next level, that was the workshop where the coffins were made.

Everything about it enthralled me, and as a boy I couldn’t wait to grow up and be able to work there if my uncle and grandma let me. All my friends at school thought it weird that I wanted to be an undertaker, and I suppose to others it did seem peculiar, but to me I couldn’t imagine doing anything else. I know quite a few people used to call me a ‘morbid little bugger’ but it didn’t bother me. I think I was originally drawn to it by the horses, as they always looked so beautiful.

My first recollections were from around the age of about five and a half, when I saw my first horse-drawn funeral leaving the yard. I can still see it to this day. It was bitterly cold and very gently snowing, and I had my tongue out trying to catch the snowflakes. My mum was holding my hand as we were walking towards the yard when the large doors opened and the cortège started to leave. She pulled me up. ‘Put your tongue in, Stan, and stand still.’ She then leant down and whispered in my ear: ‘Take your cap off and bow your head as it passes.’

‘Why, Mum?’ I asked, looking up at her.

‘It’s respect, Stan. We’re respecting the person who’s died.’

I didn’t know what she meant, but I did it – I took off my cap and bowed my head.

Everything about the scene was so spectacular it was as if I was in a film. The gleaming horses looked enormous to me. Their hooves made such a noise on the wet cobbles, and the highly polished carriages had a fine flurry of snow dancing around them. Then there was Uncle Tom with the coachmen looking impeccable in their overcoats and top hats.

I was captivated.

Even seeing the bodies fascinated me. I never once felt frightened. I don’t know why; maybe it was because I was so young and didn’t comprehend what was actually going on.

When I knew nobody was looking I would creep into the storage room where the bodies had been brought in and left on easels in ‘shells’ – these were coffins which were painted white inside and were used to fetch corpses from hospitals or homes before being prepared and placed into a ‘proper’ coffin. As I was so small I would have to drag a chair over to stand on. I would then gently slide the ...