- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

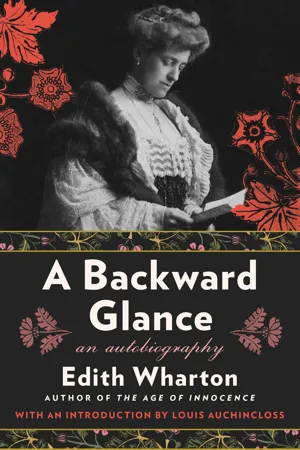

Edith Wharton, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize, vividly reflects on her public and private life in this stunning memoir.

With richness and delicacy, it describes the sophisticated New York society in which Wharton spent her youth, and chronicles her travels throughout Europe and her literary success as an adult. Beautifully depicted are her friendships with many of the most celebrated artists and writers of her day, including her close friend Henry James.

In his introduction to this edition, Louis Auchincloss calls the writing in A Backward Glance “as firm and crisp and lucid as in the best of her novels.” It is a memoir that will charm and fascinate all readers of Wharton’s fiction.

With richness and delicacy, it describes the sophisticated New York society in which Wharton spent her youth, and chronicles her travels throughout Europe and her literary success as an adult. Beautifully depicted are her friendships with many of the most celebrated artists and writers of her day, including her close friend Henry James.

In his introduction to this edition, Louis Auchincloss calls the writing in A Backward Glance “as firm and crisp and lucid as in the best of her novels.” It is a memoir that will charm and fascinate all readers of Wharton’s fiction.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Backward Glance by Edith Wharton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

X

LONDON, “QU’ACRE” AND “LAMB”

1

I MUST go back a long way to recover the threads leading to my earliest acquaintance with London society. My husband and I took our first dip into it just after the appearance of “The Greater Inclination”; but a dip so brief that I brought back from it hardly more than a list of names. It was then, probably, that I first met Lady Jeune, afterward Lady St Helier, whose friendly interest put me in relation with her large and ever-varying throng of guests. The tastes and interests of Lady St Helier, one of the best-known London hostesses of her day, could hardly have been more remote from my own. She was a born “entertainer” according to the traditional London idea, which regarded (and perhaps still regards) the act of fighting one’s way through a struggling crowd of celebrities as the finest expression of social intercourse. I have always hated “general society”, and Lady St Helier could conceive of no society that was not general. She took a frank and indefatigable interest in celebrities, and was determined to have them all at her house, whereas I was shy, or indifferent, and without any desire to meet any of them, at any rate on such wholesale occasions, except one or two of my own craft. Yet Lady Jeune and I at once became fast friends, and my affection and admiration for her grew with the growth of our friendship. For many years I stayed with her whenever I went to London, gladly undergoing the inevitable series of big lunches and dinners for the sake of the real pleasure I had in being with her. Others have done justice to her tireless and intelligent activities on the London County Council, and in every good cause, political, municipal or philanthropic, which appealed to her wide sympathies. What I wish to record is that this woman, who figured to hundreds merely as the most indefatigable and imperturbable of hostesses, a sort of automatic entertaining machine, had a vigorous personality of her own, and the most generous and independent character. Psychologically, the professional hostess and celebrity-seeker will always remain an enigma to me; but I have known intimately three who were famous in their day, and though nothing could be more divergent than their tastes and mine, yet I was drawn to all three by the same large and generous character, the same capacity for strong individual friendships.

Lady St Helier was perfectly aware of her own foible for hospitality on a large scale, and I remember her being amused and touched by an incident which happened just before one of my visits to her. One of her two married daughters shared her interest in the literary and artistic figures of the day, and as this daughter lived in the country she depended on her mother for her glimpses of the passing show. One day she wrote begging Lady St Helier to invite to dinner, at a date when she, the daughter, was to be in London, a young writer whose first book had caused a passing flutter. Lady St Helier, delighted at the pretext, wrote to the young man, who was a total stranger to her, telling him of her daughter’s admiration, and her own, for his book, and begging him to dine with her the following week. The novelist replied that he could not accept her invitation; he hated dining out, and moreover owned no evening clothes; but he added that he was desperately hard up, and as Lady St Helier had liked his book he hoped she would not mind lending him five pounds. His would-be hostess was disappointed at his refusing her invitation, but delighted with his frankness; and I am certain she sent him the five pounds—and not as a loan.

She would, I am sure, have been equally amused if she had ever heard (as I daresay she did) the story of the cannibal chief who, on the point of consigning a captive explorer to the pot, snatched him back to safety with the exclamation: “But I think I’ve met you at Lady St Helier’s!”

Among the friends I made at that friendly table I remember chiefly Sir George Trevelyan, the historian, Lord Haldane and Lord Goschen—the two latter, I imagine, interested by the accident of my familiarity with German literature. I saw at Lady St Helier’s a long line of men famous in letters and public affairs, but our meetings were seldom renewed, for my visits to London were so crowded and hurried, owing to my husband’s unwillingness to remain in England for more than a few days at a time, that the encounters were at best but passing glimpses. Thomas Hardy, however, I met several times, and though he was as remote and uncommunicative as our most unsocial American men of letters, his silence seemed due to an unconquerable shyness rather than to the great man’s disdain for humbler neighbours. I sometimes sat next to him at luncheon at Lady St Helier’s, and I found it comparatively easy to carry on a mild chat on literary matters. I remember once asking him if it were really true that the editor of the American magazine which had the privilege of publishing “Jude the Obscure” had insisted on his transforming the illegitimate children of Jude and Sue into adopted orphans. He smiled, and said yes, it was a fact; but he added philosophically that he was not much surprised, as the editor of the Scottish magazine which had published his first short story had objected to his making his hero and heroine go for a walk on a Sunday, and obliged him to transfer the stroll to a week-day! He seemed to take little interest in the literary movements of the day, or in fact in any critical discussion of his craft, and I felt that he was completely enclosed in his own creative dream, through which I imagine few voices or influences ever reached him.

One of the things that most struck me when I began to go into general society in England was this indifference of the kind and friendly people whom I met to any but their individual occupations or hobbies. At that time—over thirty years ago—an interest in general ideas, and indeed in any topic whatever outside of the political and social preoccupations of the England of the day, was almost non-existent, except in a small group with which I was not thrown until later. There were, of course brilliant exceptions, and many of the most cultivated and widely ranging intelligences I have known have been among the Englishmen of that generation. But in general, in the big politico-worldly society in which men of all sorts, sportsmen, soldiers, lawyers, scholars and statesmen, were mingled with the merely frivolous, I found the greater number rather narrowly confined to their own particular topics, and general conversation as rigorously excluded as general ideas.

I remember, at one big dinner in this portion of the London world, hearing some one name Lord Basil Blackwood as we entered the dining-room, and turning eagerly to my neighbour (a famous polo-player, I think) with the question: “Oh, can you tell me if that is the wonderful Basil Blackwood who did the pictures for ‘The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts’?” My neighbour gave me a glance of undisguised dismay, and hastily replied: “Oh, please don’t ask me that sort of question! I’m not in the least literary.” His hostess, in sending him in with me, had probably whispered to the unhappy man: “She writes”, and he was determined to make his position clear from the outset.

On another evening I had as neighbour, at another big dinner in the same set, a friendly young army officer, evidently much engrossed in his profession, who at once disarmed me by confessing that he didn’t know how to talk anything but “shop”. As I foresaw at least ten courses (I think the dinner was at Lord Rothschild’s) I was somewhat disconcerted; but the encounter must have taken place not long after the Boer War, and having just read Conan Doyle’s vivid narrative of that campaign I plunged at once into the subject, and thus kept more or less afloat for the first half hour. But what in the world were we to talk of next—? My neighbour knew I was an American, and I thought his manifest interest in military history might have led him to hear of the American Revolution. I therefore asked him if he had read Sir George Trevelyan’s lately published history of that event. He had never heard of the book or of the author, and to rouse his interest I said I had been told that Lord Wolseley regarded Sir George’s account of the battle of Bunker Hill as the finest description of a military engagement written in our day.

“Ah,” said my neighbour, with awakening interest—“the author’s a soldier himself, then, I suppose?”

“No, he’s not; which makes it all the more remarkable,” I replied ( though at the moment I was not sure that it did!).

My reply plunged the young officer into perplexity; then his face lit up. “Ah—I see; he was out there as military correspondent, was he?”

2

Now and then, of course, there were rich compensations for such evenings. I always said that London dinners reminded me of Clärchen’s song; they could be so “freudvoll” or so “leidvoll”—though “gedankenvoll” they seldom were. But in the course of my London visits I gradually made friends with various intelligent people of the world whose interests were much nearer my own. Most of them figured among the “Souls”, who prided themselves on a title which had been ironically conferred, or among a kindred set of fashionable cosmopolitans, always ready to welcome new ideas, though they could seldom spare the time to understand them. The latter group, though not affiliated to the “Souls”, yet for the most part had the same interests and amusements, and I passed some pleasant hours with both.

One night at a dinner in this milieu —I think at Lady Ripon’s—I found myself next to a man of about thirty-five or forty, whose name I had not caught. We fell into conversation, and within five minutes I was being whirled away on such a quick current of talk as I had not dipped into for many a day. My neighbour moved with dazzling agility from topic to topic, tossing them to and fro like glittering glass balls, always making me share in the game, yet directing it with a practised hand. We soon discovered a common love of letters, and I think it was our main theme that evening. At all events, what I chiefly remember is our having matched, so to speak, the most famous kisses in literature, and my producing as my crowning effect, and to my neighbour’s great admiration, the kiss on the stairs in “The Spoils of Poynton” (which I have always thought one of the most moving love-scenes in fiction), while he quoted in exchange the last desperate embrace of Troilus:

Injurious Time now with a robber’s haste

Crams his rich thievery up, he knows not how;

As many farewells as be stars in heaven …

He fumbles up into a loose adieu,

And scants us with a single famished kiss

Distasted with the salt of broken tears.

Only at the end of the evening did I learn that I had sat next to Harry Cust, one of the most eager and radio-active intelligences in London, unhappily too favoured by fortune to have been forced to canalize his gifts, but a captivating talker and delightful companion in the small circle of his intimates. We struck up a prompt friendship, and thereafter I seldom missed seeing him when I was in London, and keep the memory of delightful lunches and dinners at his picturesque house, looking out over a quiet rose-garden, a stone’s throw from the roar of Knightsbridge.

Among these fashionable cosmopolitans (of whom Lady Ripon was one of the most accomplished) I found again an old friend and contemporary, the beautiful Lady Essex, who had been Adèle Grant of New York. She lived at that time at Bourdon House, Mayfair, the charming little brick manor of a famous heiress who, in the seventeenth century, brought her immense estates to the Dukes of Westminster; one of the last, I suppose, of the old country houses to survive till our day in that intensely urban quarter. There, in the friendly setting of old pictures and old furniture of which her friends keep so happy a memory, I met a number of well-known people, among whom I remember especially Claude Phillips, the witty and agreeable director of the Wallace collection, Sir Edmund Gosse, who always showed me great kindness, Mr. H. G. Wells, most stirring and responsive of talkers, the silent William Archer, dramatic critic and translator of Ibsen, and Max Beerbohm the matchless. It was not my good luck to meet the latter often, though he was still living in London, and far from being the recluse he has since (like myself) become. But when we did sit next to each other at lunch or dinner, it was like suddenly growing wings! I don’t, alas, after all these years, remember many of our topics of conversation, or of his lapidary comments; but one of the latter still delights me. We were discussing the works of a well-known novelist whose talk was full of irony and humour, but whose fiction was heavy, and overburdened with unnecessary detail. I remarked that a woman friend of his, who was aware of this defect, had once said to me: “I believe X.’s insistence on detail is caused by his having to look at everything too closely, owing to his being so short-sighted.”

Max looked at me gravely. “Ah, really? She thinks it’s because he’s so short-sighted? I should have said it was because he was so long-winded!”

The Essexes at that time were in the habit of entertaining big week-end parties at Cassiobury, Lord Essex’s place near St Albans, and one Sunday at the end of a brilliant London season, when my husband and I motored down there to lunch, we found, scattered on the lawn under the great cedars, the very flower and pinnacle of the London world: Mr. Balfour, Lady Desborough, Lady Poynder (now Lady Islington), Lady Wemyss (then Lady Elcho), and John Sargent, Henry James, and many others of that shining galaxy—but one and all so exhausted by the social labours of the last weeks, so talked out with each other and with all the world, that beyond benevolent smiles they had little to give; and I remarked that evening to my husband that meeting them in such circumstances was like seeing their garments hung up in a row, with nobody inside.

To Adèle Essex, always a devoted friend and responsive companion, and to Lady Ripon, whose sense of fun and quick enthusiasms always delighted me, I owed on the whole the pleasantest hours of my London visits; though I should be ungrateful not to add to their names those of Sir George Trevelyan, who kept up till his death a friendly interest in my books, of Mrs. Wilfrid Meynell, Mrs. Humphry Ward and my shrewd and independent old friend, Mrs. Alfred Austin. Mrs. Meynell, whose poems I admired far more than her delicate but too self-conscious essays, became interested in me, I think, through her liking for “The Valley of Decision”, and always showed me great kindness when I was in London. On one occasion, knowing my admiration for the poetry of Francis Thompson, she carried her kindness so far as to invite me to lunch with that elusive being (having previously extracted from him a promise that he would really come). But, alas, though Mr. Meynell, for greater security, called at Thompson’s lodgings to fetch him, the poor poet was in an opium dream from which he was not to be roused; and I never met him.

The first time I lunched at Mrs. Meynell’s I was struck by the solemnity with which this tall thin sweet-voiced woman, with melancholy eyes and rather catafalque-like garb, was treated by her husband and children. Mr. Meynell, small and brisk, bustled in ahead of her, as though preceding a sovereign; and all through the luncheon Mrs. Meynell’s utterances, murmured with soft deliberation, were received in an attentive silence punctuated by: “My wife was saying the other day,” “My wife always thinks”—as though each syllable from those lips were final.

I, who had been accustomed at home to dissemble my literary pursuits (as though, to borrow Dr. Johnson’s phrase about portrait painting, they were “indelicate in a female”), was astonished at the prestige surrounding Mrs. Meynell in her own family; and at the Humphry Wards’ I found the same affectionate deference toward the household celebrity.

I was often a guest of the Wards, in London or at their peaceful country-house near Tring. There were many ties of old friendship, English and American, between us, and Mrs. Ward was unfailingly kind in her estimation of my work, and always eager to make me known to interesting people. Indeed, whenever I have been in England I have found there kindness, hospitality, and a disposition to put me at once on a footing of old friendship. I should be sorry to leave out the names of any to whom I am thus indebted, and at least must add those of Sir Ian and Lady Hamilton, still my friends and my kind hosts on my frequent visits to England, of those dear friends of my childhood, now both dead, Henry and Margaret White (he was then first secretary of our Embassy in London), of Lord and Lady Charles Beresford, Sir Edmund Gosse, Lord and Lady Burghclere, and my husband’s hospitable cousin, Mrs. Adair. Of country life I saw next to nothing, for we were never in England in the autumn and winter, and at the season when we were there my husband’s dates were so unalterable that we once missed a week-end at Mentmore with Lord Rosebery because it was considered impossible that we should postpone our sailing for a few days. I have always regretted this, as well as my having been unable to accept two or three invitations to Lord Rosebery’s house in London; for as a girl of seventeen I had met him when he came to America after his marriage, and I had a vivid memory of the light and air he let into the stuffy atmosphere of a Newport season. Unhappily I never saw him again.

Much as I enjoyed these London glimpses they are now no more than a golden blur. So many years have gone by, and that old world of my youth has been so convulsed and shattered, that as I look back, and try to recapture the details of particular scenes and talks, they dissolve into the distance. But in any case I was not made to extract more than a passing amusement from such fugitive dips into a foreign society. My idea of society was (and still is) the daily companionship of the same five or six friends, and its pleasure is based on continuity, whereas the hospitable people who opened their doors to me in London, though of course they all had their own intimate circles, were as much exhilarated by the yearly stream of new faces as a successful shot by the size of his bag. Most of my intimate friendships in England were made later, and in circumstances more favourable (to me, at any rate) than the rush and confusion of a London season. Some of the dearest of them I owe to Howard Sturgis, and to him, and to Queen’s Acre, his house at Windsor, I turn for the setting of my next scene.

3

A long low drawing-room; white-panelled walls hung with water-colours of varying merit; curtains and furniture of faded slippery chintz; French windows opening on a crazy wooden verandah, through which, on one side, one caught a glimpse of a weedy lawn and a shrubbery edged with an unsuccessful herbaceous border, on the other, of a not too successful rose garden, with a dancing faun poised above an incongruously “arty” blue-tiled pool. Within, profound chintz arm-chairs drawn up about a hearth on which a fire always smouldered; a big table piled with popular novels and picture-magazines; and near the table a lounge on which lay outstretched, his legs covered by a thick shawl, his hands occupied with knitting-needles or embroidery silks, a sturdily-built handsome man with brilliantly white wavy hair, a girlishly clear complexion, a black moustache, and tender mocking eyes under the bold arch of his black brows.

Such was Howard Sturgis, perfect host, matchless friend, drollest, kindest and strangest of men, as he appeared to the startled eyes of newcomers on their first introduction to Queen’s Acre.

It was not there, but at a dinner at Newport, that I first met him, a few years after my marriage. I did not even know who he was; but if ever there was a case of friendship at first sight it was struck up between us then and there. Like me he was a great lover of good talk, and shared my inability to enjoy it except in a small and intimate circle. Continuity in friendship he valued also as much as I did, and from that day until his death, many years later, he and I shared the same small group of intimates.

Howard Sturgis was the youngest son of Mr. Russell Sturgis, of the old Boston family of that name, who for many years had been at the head of an important American banking-house in London. Mr. Sturgis, as became an international banker, was rich, popular and hospitable, kept up a large household, and entertained a great deal in London and at Givens Grove, his country place near Leatherhead. Howard, I think, was born in England, and had probably never been to America till he came out on a visit to his Boston relations, the year I met him at Newport. His mother, Mr. Sturgis’s third wife, was also a Bostonian, and his cousinage was as large as mine in New York, and far more assiduously cultivated. Howard’s closest associations, however, were English, for he had been sent to Eton and thence to Cambridge. At Eton he had been a pupil of Mr. Ainger’s, a privilege never forgotten by an Etonian fortunate enough to have enjoyed it; and Mr. Ainger, whom I often met at Queen’s Acre, had remained one of his most devoted friends. Another friend of his youth was the eccentric and tragic William Cory Johnson, an Eton master of a different stamp, and an exquisite poet in a minor strain; and it is to Howard that I owe my precious first edition of “Ionica”, royally clothed in crimson morocco.

Mr. Russell Sturgis died when Howard was still a youth, and after his father’s death, and the marriages of his brothers and his sister, he found himself alone at home with his mother. Mrs. Sturgis, whom I never knew, is said to have been a very beautiful woman. She was as luxurious in her tastes as her husband, but, I imagine, without his gift of easy hospitality. She continued to k...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Introduction

- A First Word

- Contents

- I. The Background

- II. Knee-High

- III. Little Girl

- IV. Unreluctant Feet

- V. Friendships And Travels

- VI. Life And Letters

- VII. New York And The Mount

- VIII. Henry James

- IX. The Secret Garden

- X. London, “Qu’acre” And “Lamb”

- XI. Paris

- XII. Widening Waters

- XIII. The War

- XIV. And After

- Index