eBook - ePub

The Divine Magician

The Disappearance of Religion and the Discovery of Faith

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this mind-bending exploration of traditional Christianity, firebrand Peter Rollins turns the tables on conventional wisdom, offering a fresh perspective focused on a life filled with love.

Peter Rollins knows one magic trick—now, make sure you watch closely. It has three parts: the Pledge, the Turn, and the Prestige. In Divine Magician, each part comes into play as he explores a radical view of interacting with the world in love.

Rollins argues that the Christian event, reenacted in the Eucharist, is indeed a type of magic trick, one that is echoed in the great vanishing acts performed by magicians throughout the ages. In this trick, a divine object is presented to us (the Pledge), disappears (the Turn), and then returns (the Prestige). But just as the returned object in a classic vanishing act is not really the same object—but another that looks the same—so this book argues that the return of God is not simply the return of what was initially presented, but rather a radical way of interacting with the world. In an effort to unearth the power of Christianity, Rollins uses this framework to explain the mystery of faith that has been lost on the church. In the same vein as Rob Bell’s bestseller Love Wins, this book pushes the boundaries of theology, presenting a stirring vision at the forefront of re-imagined modern Christianity.

As a dynamic speaker as he is in writing, Rollins examines traditional religious notions from a revolutionary and refreshingly original perspective. At the heart of his message is a life lived through profound love. Just perhaps, says Rollins, the radical message found in Christianity might be one that the church can show allegiance to.

Peter Rollins knows one magic trick—now, make sure you watch closely. It has three parts: the Pledge, the Turn, and the Prestige. In Divine Magician, each part comes into play as he explores a radical view of interacting with the world in love.

Rollins argues that the Christian event, reenacted in the Eucharist, is indeed a type of magic trick, one that is echoed in the great vanishing acts performed by magicians throughout the ages. In this trick, a divine object is presented to us (the Pledge), disappears (the Turn), and then returns (the Prestige). But just as the returned object in a classic vanishing act is not really the same object—but another that looks the same—so this book argues that the return of God is not simply the return of what was initially presented, but rather a radical way of interacting with the world. In an effort to unearth the power of Christianity, Rollins uses this framework to explain the mystery of faith that has been lost on the church. In the same vein as Rob Bell’s bestseller Love Wins, this book pushes the boundaries of theology, presenting a stirring vision at the forefront of re-imagined modern Christianity.

As a dynamic speaker as he is in writing, Rollins examines traditional religious notions from a revolutionary and refreshingly original perspective. At the heart of his message is a life lived through profound love. Just perhaps, says Rollins, the radical message found in Christianity might be one that the church can show allegiance to.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

SECTION FOUR

BEHIND THE SCENES

CHAPTER 7

Outside the Magic Circle

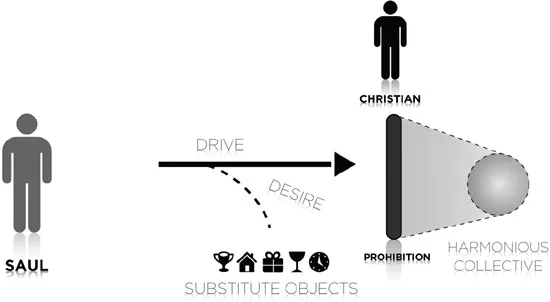

This experience of working through the Pledge, Turn, and Prestige is a personal experience, but it is equally connected to wider concerns. Such a movement is a political happening, insofar as it transforms how we interact with the world.

This interconnection between the personal and political can be seen in the paradigmatic expression of conversion in Christianity. Namely the transformation of Saul on the road to Damascus:

Meanwhile, Saul was still breathing out murderous threats against the Lord’s disciples. He went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues in Damascus, so that if he found any there who belonged to the Way, whether men or women, he might take them as prisoners to Jerusalem. As he neared Damascus on his journey, suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice say to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?”

“Who are you, Lord?” Saul asked.

“I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting,” he replied. “Now get up and go into the city, and you will be told what you must do.”

The men traveling with Saul stood there speechless; they heard the sound but did not see anyone. Saul got up from the ground, but when he opened his eyes he could see nothing. So they led him by the hand into Damascus. For three days he was blind, and did not eat or drink anything.

In Damascus there was a disciple named Ananias. The Lord called to him in a vision, “Ananias!”

“Yes, Lord,” he answered.

The Lord told him, “Go to the house of Judas on Straight Street and ask for a man from Tarsus named Saul, for he is praying. In a vision he has seen a man named Ananias come and place his hands on him to restore his sight.”

“Lord,” Ananias answered, “I have heard many reports about this man and all the harm he has done to your holy people in Jerusalem. And he has come here with authority from the chief priests to arrest all who call on your name.”

But the Lord said to Ananias, “Go! This man is my chosen instrument to proclaim my name to the Gentiles and their kings and to the people of Israel. I will show him how much he must suffer for my name.”

Then Ananias went to the house and entered it. Placing his hands on Saul, he said, “Brother Saul, the Lord—Jesus, who appeared to you on the road as you were coming here—has sent me so that you may see again and be filled with the Holy Spirit.” Immediately, something like scales fell from Saul’s eyes, and he could see again. He got up and was baptized, and after taking some food, he regained his strength.1

We see here that Saul was utterly dedicated to persecuting a new religious sect that had grown out of Judaism. For Saul, this nascent group was a type of virus that had to be destroyed.

In this way, the Christian community functioned as a scapegoat for Saul: they were a thorn in the side of the existing religious structure that needed to be removed in order to ensure a harmonious and unified religious community.

Saul’s Obstacle

While Saul experiences the Christian community as an external growth that threatened the status quo, the community arose from within the religious structure that Saul represented. Like all such growths, the new community’s very existence signified an issue within the religious structure of the day. In this sense, they were a symptom, i.e., the material manifestation, of an issue that was not being addressed.

This is not unlike the way that the Reformation functioned in relation to the Catholic Church of Luther’s day, for his critique arose as a direct result of internal problems within the institution of the day and gained its power through the church’s failure to face those problems.

What we witness in such examples is how a new religious or political community (whether positive or negative) arises as the direct response to a deadlock in the existing system. They are attempts to resolve antagonisms that are being repressed or disavowed in the community they are responding to.

By treating the new Christian community as a foreign intruder rather than as a symptom, Saul was effectively avoiding a confrontation with the problems that had given rise to this group in the first place. Thus the peace that Saul might have imagined would result from the destruction of the Christians was a fantasy, a veil obscuring the truth of a problem within the existing religious order.

The imagined gridlock that Saul believed existed because of the movement actually helped to eclipse the very gridlock that gave birth to the movement.

What we are confronted with in the description of Saul’s conversion is the way that he related to the Christian community as a scapegoat: he falsely perceived them to be the problem, when understanding that community would have actually helped to confront and overcome the problem.

To take a different example, we can reflect upon how homelessness in a society is generally seen as a problem that needs to be addressed, rather than being seen as a solution to a problem within the society. Without acknowledging this, any strategy aimed at removing homelessness is doomed to failure. For unless one understands how the homeless function in a society, then the real issue won’t be addressed. If one is able to solve homelessness in a given society without addressing what gave rise to the problem, something else will simply take its place. Instead, the reason for the existence of the homeless must be assessed. In this way, the homeless become a voice of salvation to the very society that creates them.

Another example is the societal denial evidenced in the laws that protect people from being tortured for religious or political beliefs. The very existence of these laws signals a moral failing, in that only a society that creates the conditions for such torture needs to make a law that attempts to protect people from it. The idea of the oppressed and powerless being a prophetic voice to the system can be easily misunderstood. For it might seem to claim that an oppressed group is necessarily more moral than one that is not. This is obviously false when we consider how certain racist groups, for instance, are not given equal voice in a society. The point is not that they have a legitimate voice, but rather that their very existence signals a problem within the society that gave birth to them. Simply attempting to get rid of such a group will be ineffective if we do not strive to understand and address the situation that enabled them to gain a foothold.

When considering Saul’s conversion, we see a dramatic example of how the position of the outsiders offers a call to transformation. In the narrative, those he believed to be damned were suddenly revealed as the path to salvation. On the road to Damascus, he heeds a voice that informs him that he is in fact persecuting God. His conversion mimics the theological meaning of the Crucifixion, for Christ is treated as a scapegoat who turns out to be the way of salvation.

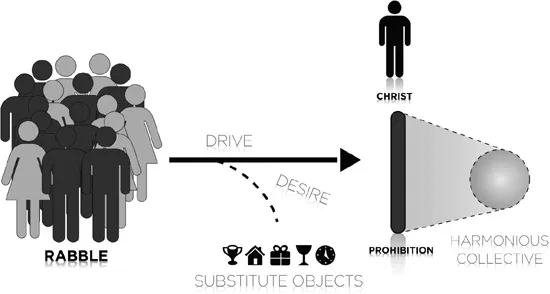

This is where the theological conservative comes closest to the radical position, for the conservative also associates Christ with the torn curtain of the temple, but for very different reasons. While the conservative reads Christ as the curtain who is “torn” so that we can gain what lies on the other side, the radical interpretation sees Christ as the curtain that, when torn, reveals the emptiness of what lies on the other side. Here the conservative interpretation is structurally the same as that of the rabble gathered at the trial of Jesus, with the exception that for the rabble, Jesus is the obstacle that must be abolished to fulfill the law, while for the conservative, Jesus is the lamb that must be sacrificed to fulfill it.

Christ the Scapegoat

In contrast, the radical reading claims that the very act of scapegoating is a fundamental failure, but a failure that opens up a victory. For it is when we realize that the destruction of the scapegoat is powerless to help that we can realize that listening to the scapegoat is where the transformation lies.

In this radical reading of Christ’s crucifixion, it is only after Christ has been killed that we realize the failure of our scapegoating and the reality that what we thought we needed to destroy in order to get to the sacred was in fact sacred. This is captured powerfully in the response of the Roman centurion who proclaims, “Surely this was the son of God,” once Jesus has died.2

Here the centurion symbolically stands in for the one who realizes that the obstacle was in fact the way.

This can help us understand why one of the terms for Christ is the rejected stone that became the capstone. For in architectural terms, the capstone is what anchors a given structure; it is the stone that is placed at the highest point in an arch to ensure that everything else stays in place. Here the stone that is thrown away is revealed as the stone that is most central.

The logic of the cross exposes the scapegoat as the way of salvation.

Another interesting example of this can be seen in the position that the Samaritan is given in the Gospel writings. The Samaritans were a people with both Jewish and pagan ancestry and who diverged somewhat from the practices of mainstream Judaism. They were largely disliked and viewed with suspicion by the religious establishment of the day. Indeed, rather than pass through Samaritan territory, many Jews who were traveling between Judea and Galilee would take a much longer route to get to their destination.

It’s clear that the importance Jesus placed on the Samaritans was not related to their particular beliefs and practices (which he doesn’t mention), but rather to their lowly position within the religious system of the day. The parable of a Samaritan who helps someone on the side of the road is a clear challenge to the way the Samaritans were being scapegoated. In this parable, the Samaritan is placed in the position of the godly act, thus turning the dominant prejudice of the day on its head.

It is on the road to Damascus that we see this insight taking place in the life of Saul. In a brief moment, he realizes that the group he’s persecuting is not what stands in the way of his salvation, but is the very path to salvation.

On his way to Damascus he’s directly confronted with his own violence devoid of any sacred justification. He experiences the persecuted community as a prophetic voice addressed to him, and he heeds the message.

In an act of profound grace, the traumatized Saul is welcomed in and cared for by one of the very people he has been seeking to destroy. Then, when he is better, he demonstrates the reality of his transformation by committing himself to a very different mission. He changes his name to Paul, and he dedicates himself to the formation of a new type of community—one that questions the final legitimacy of a religious identity or confessional tradition. He dedicated himself to a community of neither/nor—neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, neither male nor female.3 By breaking down these tribal identities, he drains scapegoating of its power. This is not to say that Paul wasn’t a man of his times with views that reflect those of his day, but his lasting insight was one of a new type of community that would cut against the various tribal identities in operation at the time. A vision that has as much power and significance for us now as it did then.

It is this disturbing, disruptive, and destabilizing idea of neither/nor that has been domesticated and effectively silenced in the church, arising only on the edges of the religious tradition in mystics like Meister Eckhart (who was accused of heresy) and Marguerite Porete (who was burned at the stake).

Paul’s conversion offers us a glimpse of what it might mean to form communities of practice where the scapegoat is smashed and where we exorcise the demonic power of exclusionary systems—communities where we learn what it might look like to embrace equality, solidarity, and universal emancipation.

This new community envisaged by Paul is not some alternative to what already exists, but rather is a vision that can be adopted by already existing communities. If it were as simple as the idea of creating some new group, this would itself become its own new tradition that would need to be challenged. This idea of the neither/nor should be approached as a way of revolutionizing already existing communities.

The attempt to open already existing communities to what they exclude might well lead to new groups—that is, if the attempt is rejected—but it might also lead to the transformation of what already is.

While a new grouping grew out of Paul’s mission—the Christian Church—the point of neither/nor collectives is not to create a new ideological cult, but to break open already existing ideological systems.

By taking this approach to Paul, we gain a picture of what it might be like to found a community that is not in submission to its political, cultural, and religious markers. Of course, new communities will arise out of old ones, and no community will ever be free of bias, conflict, and prejudices. But the possibility is held out for communities that are willing and able to challenge themselves, face their internal conflicts, and strive to better enact liberation.

A King Is a King Because We Treat Him as One

Such a collective, as we have already mentioned, wrestles with the ideological systems it is immersed in. The demand to wrestle with God as a trickster becomes the model for how we must wrestle with any order that justifies us and holds everything in place.

Ideology is the justification of an actual state of affairs that polices the boundaries between what is considered pure and impure, good and bad, inside and outside. At the time of Paul the system that held sway broadly defined people in terms of one’s identity as a Jew or a Gentile, a male or female, a slave or a free person. Each of these identities carried with it certain roles and responsibilities, with some being valued more highly than others.

The system was taken to be divinely established, and so to question it was not simply to debate the political and religious structure, but to rebel against the laws of nature and the will of God. Even if people didn’t actually believe in God or natural law, the population acted as if it were true—either through fear, custom, self-preservation, or profit. It is this bodily commitment to a social order that manifests ideology at its zero level—as a system that continues to operate even among those who do not intel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Introduction: Hocus-Pocus

- Section One: The Pledge

- Section Two: The Turn

- Section Three: The Prestige

- Interlude: Trickster Christ

- Section Four: Behind the Scenes

- Conclusion: In the Name

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Divine Magician by Peter Rollins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.