![]()

PART ONE

Beginnings

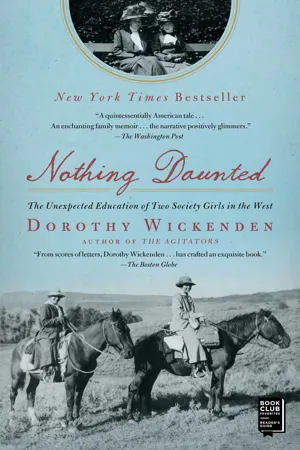

Dorothy in 1899, age twelve

![]()

1

OVERLAND JOURNEY

JULY 27, 1916

A passenger train pulled into the Hayden depot at 10:45 P.M. with a piercing squeal of brakes, a long whistle, and the banging of steel shoes against couplers. The ground shook as the train settled on the tracks, releasing black plumes from the smokestack and foggy white steam from the side pipes. The Denver, Northwestern & Pacific Railway, popularly known as the Moffat Road, had reached Hayden just three years earlier. Until then, Colorado’s Western Slope was accessible only by stagecoach, wagon, horseback, and foot. Despite the hulking locomotive, the train didn’t look quite up to the twelve-hour journey it had just made over some of the most treacherous passes and peaks of the Rocky Mountains. It consisted of four cars with an observation deck attached at the end. Inside the parlor car, several passengers remained. Hayden was the second-to-last stop on the line.

Dorothy Woodruff and Rosamond Underwood, seasoned travelers in Europe but new to the American West, peered out the window into a disconcerting darkness, unsure whether it was safe to step outside. Then the door of the compartment opened, and a friendly voice called out, “Are you Miss Woodruff and Miss Underwood?” The voice belonged to their employer, Farrington Carpenter. Just a few weeks earlier, he had hired them to teach for the year at a new schoolhouse in the Elkhead Mountains, north of town. His letters, written from his law office in Hayden, were full of odd, colorful descriptions of Elkhead and the children—about thirty students, from poor homesteading families, ranging in age from six to nineteen. Carpenter had assured them it was not a typical one-room schoolhouse. It had electric lights, and the big room was divided by a folding wooden partition, so that each of them could have her own classroom. The basement contained a furnace, a gymnasium, and a domestic science room. Notwithstanding its remote location, he boasted, it was the most modern school in all of Routt County—an area of two thousand square miles.

Ros observed with surprise that “Mr. Carpenter” was a “tall, gangly youth.” He wore workaday trousers, an old shawl sweater, and scuffed shoes. She subsequently discovered that he had graduated from Princeton in 1909, the same year she and Dorothy had from Smith. But when they were traveling around Europe and studying French in Paris, he was homesteading in Elkhead. In 1912 he had earned a law degree at Harvard. He retrieved their suitcases from the luggage rack and helped them down the steep steps, explaining that the electricity in Hayden, a recent amenity, had been turned off at ten P.M., as it was every night.

The baggage man heaved their trunks onto the platform, and Carpenter assessed the cargo. Dorothy and Ros had been punctilious in their preparations for the journey, packing suitcases full of books and the two “innovation trunks,” which stood up when opened and served as makeshift closets, holding dresses and skirts on one side and bureau drawers on the other. Although they had consulted several knowledgeable people about the proper supplies and clothing, their parents kept urging them to take more provisions. Ros later commented that they were treated as if they were going to the farthest reaches of Africa. Their trunks were almost the size of the boxcar in front of them, which, the women could now make out, was the extent of the depot. Carpenter told them that a wagon would come by the next morning to retrieve the trunks. As he picked up their bulging suitcases and set off, Dorothy suggested sheepishly that he leave them with the trunks. He replied, “Well, no one would get far with them!”

Dorothy and Ros liked him immediately. He staggered down the wooden sidewalk along Poplar Street to the Hayden Inn, followed closely by the ladies. Ros wrote to her parents the next morning, “Why he didn’t pull his arms out of their sockets before reaching here, I don’t know.” There was no reception desk at the Hayden Inn, and no proprietor. Putting down the suitcases inside the cramped entryway, Carpenter turned up a kerosene lamp on the hall table and promised to meet them at breakfast. They found a note by the lamp: “Schoolteachers, go upstairs and see if anyone is in Room 2. If they are, go to Room 3, and if 3 is filled, go to Room 4.” When Dorothy cracked open the door to Room 2, she could see that it was occupied, so they crept along the hall to the back of the house and found that the next room—“the bridal suite”—was empty. “We went to bed,” Ros said, “glad to be there after that long trip.”

—————————

They had said goodbye to their parents at New York Central Station in Auburn five days earlier. Auburn, a city of about thirty thousand people in the Finger Lakes district, was one of the wealthiest in the state. Ros’s father, George Underwood, was a county judge, and Dorothy’s, John Hermon Woodruff, owned Auburn Button Works, which made pearl and shellac buttons, butt plates for rifles, and later, 78-rpm records. The Button Works and the Logan silk mills, jointly owned by Dorothy’s father and a maternal uncle, were housed in a factory about a mile north of the Woodruffs’ house. They were two of the town’s early “manufactories.” Others produced rope, carpets, clothes-wringers, farm machinery, and shoes. Auburn’s main arteries, Genesee and South streets, which formed a crooked T, were more like boulevards in the residential neighborhoods, lined with slate sidewalks and stately homes. Majestic old elms arched across and met in the middle. The ties within families and among friends were strong, and the local aristocracy perpetuated itself through marriage. Men returned from New York City after making money in banking or railroads; opened law practices and businesses in town; or worked with their brothers and fathers, cousins and uncles. Some never left home at all. Sons and daughters inherited their elders’ names and their fortunes. Most women married young and began building their own families. One chronicler observed, “Prick South Street at one end, and it bleeds at the other.”

Dorothy, less composed and orderly than Rosamond, had arrived at the station only moments before the train left for Chicago, and as she climbed aboard, she could almost hear her mother saying “I told you so” about the importance of starting in plenty of time. Her last glimpse of her parents was of her father’s reassuring smile. He and Ros’s mother championed their adventure. Her mother and Ros’s father, though, were convinced their daughters would be devoured by wild animals or attacked by Indians. When Ros showed her father one of Carpenter’s letters, he turned away and put up his hand, saying, “I don’t want to read it.”

The girls prevailed, as they invariably did, when their parents saw they were determined to go through with their plans. As Mrs. Underwood put it, “They were fully competent to decide this question.” Although intent on their mission, they had bouts of overwhelming nervousness about what they had taken on. During the ride to Chicago, they took notes from the books on teaching that Dorothy had borrowed from a teacher in the Auburn schools. They also reread the letter they had received the previous week from Carpenter:

My dear Miss Woodruff and Miss Underwood,

I was out to the new school house yesterday getting a line on how many pupils there would be, what supplies and repairs we would need etc. . . . I have not heard from you in regard to saddle ponies, but expect you will want them and am looking for some for you. . . .

I expect you are pretty busy getting ready to pull out. If you have a 22 you had better bring it out as there are lots of young sage chicken to be found in that country and August is the open season on them.

With best regards to you both I am very truly

Farrington Carpenter

They were met at the Chicago station by J. Platt Underwood, an uncle of Ros’s, who was, Dorothy observed, “clad in a lovely linen suit.” A wealthy timber merchant, he did much of his business in the West, and when they told him that Carpenter had advised them to bring along a rifle, he agreed it was a good idea. The next morning he took them from his house on Lake Park Avenue into the city to buy a .22 and a thousand rounds of shot. It was already 90 degrees downtown and exceedingly humid. Dorothy wrote to her mother that everyone laughed when she tried to pick up the rifle. “I could hardly lift the thing. . . . Imagine what I’ll be in Elkhead!” She had better luck at Marshall Field’s, where she found a lovely coat: “mixed goods—very smart lines & very warm for $30.00.” She and Ros bought heavy breeches at the sport store and got some good leather riding boots that laced up the front.

The oppressive heat wave followed them as they left Chicago, and it got worse across the Great Plains, clinging to their skin along with the dust. Although transportation and safety had improved since the opening of the West, and there were settlements and farms along the railway, the scenery, if anything, was starker than ever. When they were several hundred miles from Denver, there were few signs of life. The riverbeds were cracked open, and there was no long, lush prairie grass or even much sagebrush, just furze and rush and yucca. The few trees along the occasional creeks and “dry rivers” were stunted. The Cheyenne and Arapaho and the awkward, hunchbacked herds of buffalo that had filled the landscape for miles at a stretch were gone. From the train window, Dorothy and Ros caught only an occasional glimpse of jackrabbits.

They had not been aware of the gradual rise in terrain, but they were light-headed as they stepped into the Brown Palace Hotel in Denver. Ros was tall, slender, and strikingly pretty, with a gentle disposition and a poised, steady gaze—“the belle of Auburn,” as Dorothy proudly described her. Dorothy’s own round, cheerful face was animated by bright blue eyes and a strong nose and chin. People tended to notice her exuberant nature more than her small stature. Under their straw hats, their hair had flattened and was coming unpinned.

Half a dozen well-dressed gentlemen sat in the lobby on tufted silk chairs, reading newspapers or talking; women were relaxing in the ladies’ tearoom. A haberdashery and a barbershop flanked the Grand Staircase, and across the room was a massive pillared fireplace made of the same golden onyx as the walls. The main dining room, with gold-lacquered chairs and eight-foot potted palms, was set for dinner. As they approached the reception desk, they saw that the atrium soared above the Florentine arches of the second story. Each of the next six floors was wrapped in an ornate cast-iron balcony, winding up to a stained-glass ceiling. The filtered light it provided, along with the high wall sconces, was pleasantly dim, and it was relatively cool inside.

Ros signed the register for both of them—Miss D. Woodruff and Miss R. Underwood—in neat, girlish handwriting, with none of the sweeping flourishes of the male guests who had preceded them from Kansas City, Philadelphia, Carthage, and Cleveland. On a day when they would have welcomed a strong rain, they were courteously asked whether they preferred the morning or afternoon sun. A bellman showed them to Room 518, with a southeastern exposure and bay windows overlooking the Metropole Hotel and the Broadway Theatre. They were delighted to see that they also had a private bathroom with hot and cold running water. Each of them took a blissful bath, and despite Dorothy’s assurances to her mother after her purchases at Field’s (“Nothing more for nine months!”), they went straight to Sixteenth Street to shop. They had no trouble finding one of the city’s best department stores, Daniels & Fisher. Modeled after the Campanile at the Piazza San Marco, it rose in stately grandeur high above the rest of downtown.

Denver was up-to-date and sophisticated. Its public buildings and best homes were well designed, on a grand, sometimes boastful scale. The beaux arts Capitol—approached by paved sidewalks and a green park—had a glittering gold-leaf dome. There was a financial district on Seventeenth Street known as “the Wall Street of the West”; a YMCA; a Coca-Cola billboard; electric streetcars; and thousands of shade trees. Under the beautification plan of Mayor Robert Speer, the city had imported oaks, maples, Dutch elms, and hackberries, which were irrigated with a twenty-four-mile ditch carrying water from the streams and rivers of the Rockies. The desert had been transformed into an urban oasis.

—————————

Dorothy and Ros had heard about the Pike’s Peak gold rush of 1859, and they could see how quickly the city had grown up, but beyond that, their knowledge of early Western history was hazy. It was hard to imagine that not even sixty years earlier, Denver City, as it was then called, was a mining camp with more livestock than people. Still part of Kansas Territory, it consisted of a few hundred tents, log cabins, Indian lodges, and shops huddled on the east bank of Cherry Creek by the South Platte River. The cottonwoods along the creek were chopped down for buildings and fuel. Pigs wandered freely in search of garbage. Earthen roofs dripped mud onto the inhabitants when it rained, and they frequently collapsed. The only hotel was a forty-by-two-hundred-foot log cabin. It had no beds and was topped with canvas.

The more visionary newcomers looked past the squalor. One of them was twenty-eight-year-old William Byers, who started the Rocky Mountain News. In his first day’s edition of the paper, he declared: “We make our debut in the far west, where the snowy mountains look down upon us in the hottest summer day as well as in the winters cold here where a few months ago the wild beasts and wilder Indians held undisturbed possession—where now surges the advancing wave of Anglo Saxon enterprise and civilization, where soon we fondly hope will be erected a great and powerful state.” Already Byers was Colorado’s most strident advocate, and he became part of the business and political class that made sure his predictions came true. Thousands of prospectors, stirred by exaggerated tales about gold discoveries, imagined the region as “the new El Dorado.”

Few valuable minerals were found at Pike’s Peak until long after the gold rush had ended. Nevertheless, in the winter and spring of 1859, the first significant placer deposits were found, in the mountains at Clear Creek, thirty-five miles west of Denver; they were soon followed by finds at Central City, Black Hawk, and Russell Gulch. By the end of the year, a hundred thousand prospectors had arrived.

Denver City became an indispensable rest and supply stop for gold diggers on their way to and from the Rockies, as it was for trail drivers and lumbermen. Wagon trains from Missouri and Kansas came to town filled with everything from picks and wheel rims to dry goods, whiskey, coffee, and bacon. Gold dust was the local currency, carried in buckskin pouches and measured on merchants’ scales. There was enough of it to start a building boom in everything from gambling halls to drugstores.

With the accumulation of creature comforts in Denver, some speculators were confident that they could domesticate the mountains, too, with dozens of towns and resorts. In the meantime, men returned with stories of suffering and gruesome deaths in the wilderness. In June 1859 a forest fire swept through the dry pines on gusty winds, killing over a dozen people. Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, had recently stopped in Denver during his famous “Overland Journey,” and he m...