eBook - ePub

Myth, Memory, and Massacre

The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In December 1860, along a creek in northwest Texas, a group of U.S. Cavalry under Sgt. John Spangler and Texas Rangers led by Sul Ross raided a Comanche hunting camp, killed several Indians, and took three prisoners. One was the woman they would identify as Cynthia Ann Parker, taken captive from her white family as a child a quarter century before.The reports of these events had implications far and near. For Ross, they helped make a political career. For Parker, they separated her permanently and fatally from her Comanche husband and two of her children. For Texas, they became the stuff of history and legend.In reexamining the historical accounts of the "Battle of Pease River," especially those claimed to be eyewitness reports, Paul H. Carlson and Tom Crum expose errors, falsifications, and mysteries that have contributed to a skewed understanding of the facts. For political and racist reasons, they argue, the massacre was labeled a battle. Firsthand testimony was fabricated; diaries were altered; the official Ranger report went missing from the state adjutant general's office. Historians, as a result, have unwittingly used fiction as the basis for 150 years of analysis.Carlson and Crum's careful historiographical reconsideration seeks not only to set the record straight but to deal with concepts of myth, folklore, and memory, both individual and collective. Myth, Memory, and Massacre peels away assumptions surrounding one of the most infamous episodes in Texas history, even while it adds new dimensions to the question of what constitutes reliable knowledge.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Myth, Memory, and Massacre by Paul H. Carlson,Tom Crum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia de Norteamérica1

BACKGROUND

Establishing the Context

History and legend often mix. The mixing, writes folklorist B. A. Botkin, “has given rise to a large body of unhistorical ‘historical’ traditions” and the enactment of “doubtful events [by] historical characters.” The popular tale of George Washington cutting down the cherry tree, an event that did not happen, serves as a marvelous illustration of Botkin's reasoning. In Texas, a classic example of Botkin's argument is the apocryphal story of the line drawn in the dirt by William Barrett Travis at the Alamo in 1836. Travis, of course, did not draw any such line, but the dramatic anecdote is so deeply etched in Texans' collective memory that it must have happened. In this instance folklore became history.1

Indeed, such oft-repeated tales and “bigger-than-life portrayals” helped to create a “mythic nineteenth-century Texas” that was built on a whole series of falsehoods, suggests Sandra L. Myres. It is a mythic Texas, she writes, “perpetuated in art, literature, folklore, and common belief [and] enshrined in many of the history books.” Myres concludes, “If you doubt this check the textbooks used in public schools and colleges.” Similarly, Walter L. Buenger and Robert A. Calvert, in the introduction to their book Texas Through Time: Evolving Interpretations, write about the myths of various groups of Texans. They note, however, that the dominant culture has created and added to the overarching myths, or traditional knowledge, to the extent that few openly question their premises. The myths have become cherished as sacred. But recently in a whole series of books and articles historians have begun to challenge the myths and conventional beliefs that form the state's collective memory.2

One such myth surrounds the 1860 Battle of Pease River. During that brief encounter, Texas Rangers and federal troops forcibly took Naudah (Cynthia Ann Parker) and removed the thirty-four-year-old mother and her young daughter from their Comanche family and friends. Naudah did not see her sons or husband again, and her new life among the extended Parker kin of Texas remained a troubled and unhappy one.

The Pease River story, although muddled, forms a vivid part of the state's collective memory. Its mythic character began soon after the encounter as stories of Parker's “recovery” spread and people exaggerated the battle's magnitude and importance. As early as 1929 Araminta McClellan Taulman, a member of the large Parker family, sent a letter to J. Marvin Hunter, editor of Frontier Times. In it she wrote, “I will venture to say that there have been more different erroneous stories written and printed about Cynthia Ann Parker than any person who ever lived in Texas.”3 Taulman may have been right, at least as far as the Battle of Pease River and Parker's 1860 capture are concerned.

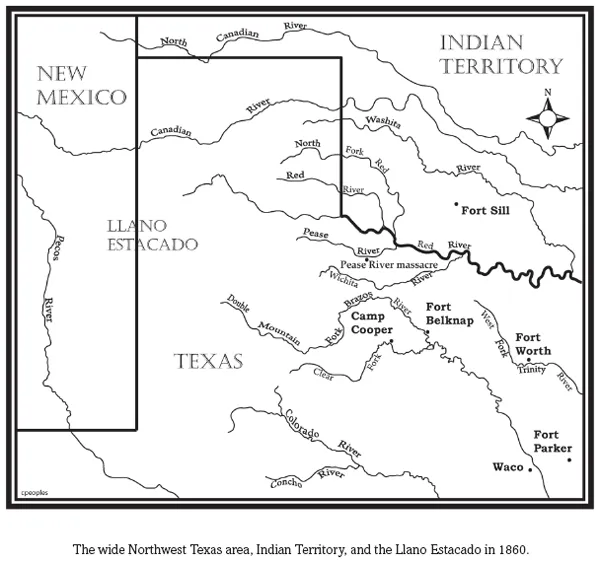

The battle—or massacre, really—occurred early on December 19, 1860, a cold, bone-chilling morning. The reports, diary entries, and personal accounts from those involved in the attack vary. Nonetheless, they suggest that fewer than twenty Texas Rangers with twenty federal troops charged into a small Comanche hunting camp along Mule Creek near its junction with the Pease River in modern Foard County. In the village of not more than nine dwellings, approximately fifteen Comanches had been dismantling tepees and packing horses and mules, and when attacked they were moving out of the camp, headed for the Llano Estacado, where they planned to rejoin their families. They were members of a kin-dominated hunting band in the small Noconi (Nokoni) division of the Comanches.

According to at least one participant's account in 1928, the surprise attack was not much of a battle. “I was in the Pease river fight,” Texas Ranger Hiram B. Rogers admitted, “but I am not very proud of it. That was not a battle at all, but just a killing of squaws.” The early morning strike claimed the lives of “one or two” men, Rogers said, and several women.4

The guns-blazing, Hollywood-style attack lasted between twenty and thirty minutes. Most of the Comanche women, because they were running away, in all likelihood were shot in the back. When it was over, the Texas Rangers and federal troops had killed seven Comanches, at least four of them women, and had taken three captives: Cynthia Ann Parker; her daughter, Topsannah (Prairie Flower); and a boy whom Lawrence Sullivan “Sul” Ross, the Ranger captain, took back to Waco and named Pease Ross.5 Among the Anglo participants there were no casualties, not even minor injuries.

For the Comanches it was a tragic event. In addition to the slaughter and kidnapping, the Anglos also captured about forty horses, destroyed camp equipage, collected many fresh bison hides and robes, and deprived the Indians of tons of meat and lard they needed to survive a winter that had just begun. Although no firsthand Comanche accounts of the battle exist, Comanche oral tradition differs little from the conclusions in this book.6

In the Anglo community, at first, except for the capture of Parker, the incident by most measures was a minor clash. As time passed, however, new and sometimes changing accounts and general histories of the episode magnified public perceptions of the fight. In part, they turned a brief, one-sided skirmish into a major battle. Indeed, at least one of the alleged participants, Benjamin F. Gholson, stated that between 150 and 200 warriors were present when the little band of forty white men charged the Indian village, which contained “between 500 and 600” Comanches.7

Although not more than forty men were involved in the actual charge through the Comanche village, three separate groups made up the larger expedition. In one, Captain Sul Ross led forty Texas Rangers. In another, First Sergeant John W. Spangler commanded about twenty federal troops from Company H of the Second Cavalry, at the time stationed at Camp Cooper, a military post on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River in Throckmorton County. Captain J. J. “Jack” Cureton led the third group of between seventy and ninety-six militiamen (citizens) from Palo Pinto, Young, and neighboring counties.

Several of the men who were part of the expedition provided reports, wrote diaries, or left reminiscences. Their experiences and perceptions of the fight varied, and understandably in second reports or subsequent descriptions a few of the men left out information that had appeared in earlier statements or added new material. In a more curious instance, someone changed Jonathan H. Baker's diary describing events associated with the expedition. Over a period of nearly thirty years Sul Ross gave at least five separate and sometimes different accounts of the Pease River fight, each of which either Ross or another person recorded. Which accounts should history accept?

Moreover, through an unwitting and, granted, minor error that nonetheless continues to be repeated, the date of the fight, December 19, 1860, got changed to the previous day. The problem with this mistake is that it is now etched in stone: the State of Texas in 1936 engraved the date on a granite historical marker erected near the battle site. It is also the date cited in the articles on Cynthia Ann Parker and Peta Nocona in The New Handbook of Texas. The almost universal acceptance of the erroneous date by those who write about the battle is indication of their unquestioned acceptance of a description of events by Sul Ross that became the conventional or authorized account.

The erroneous December 18 date first appeared in 1875. In the early 1870s, Sul Ross wrote a letter to the Galveston News in which he used the incorrect date, but for unexplained reasons the letter was not published until June 3, 1875. Two weeks later, on June 19, the same letter appeared in the Dallas Weekly Herald. But the date of December 18 is in conflict with an account Ross had given on December 23, 1860, just four days after the massacre, to a correspondent of the Dallas Herald. It is also in opposition to Ross's official report of the fight, to a diary entry by militiaman Jonathan Baker, to the eyewitness report of Peter Robertson, to the December 1860 post returns of Camp Cooper, and to the December 24, 1860, and January 16, 1861, military reports of Sergeant Spangler, all of which document the actual date as December 19.8

More egregious are the accounts of Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Gholson. Gholson, who most likely was not even a member of the expedition, left at least two sets of reminiscences that refer to the fight. His accounts of the battle along Mule Creek seem incredible, and they vary from those of the other participants to such an extent that their authenticity is suspect. Even if Gholson was present, his faulty description of events renders his testimony nearly inadmissible. Yet many modern histories of the Battle of Pease River and the 1860 capture of Cynthia Ann Parker rely on Gholson's troublesome reminiscences.9

Clearly, then, there are varying and strikingly different eyewitness reports of the Pease River fight. As a result of these and other troublesome documents, historians, biographers, journalists, and others working through the various contrasting and sometimes conflicting accounts have produced studies that have created a host of nagging questions. Did Peta Nocona (Puttack), the husband of Cynthia Ann Parker, die in the battle, as some writers maintain? If so, why, in such a society as that of the Comanches, in which gender roles were clear and specific, was Nocona, who was described by Sul Ross, possibly for his own benefit, as “a warrior of great repute,” assisting women in butchering game, striking tepees, and packing horses? Or did Puttack live for several more years, as his son Quanah and the respected scout and interpreter Horace P. Jones, who knew Puttack, stated?10

As any police investigator will attest, human memory is often unreliable. It shifts and changes, and over time the details of an event become foggy or forgotten. Even the larger picture fades like an old color photo. The mind attaches some hues and tones to its picture in such a way that, as historian David Thelen writes, memory “is constructed not reproduced.” Humans, he explains, “reshape their recollections of the past to fit their present needs.”11 Such reshaping muddies much of the story of the Battle of Pease River and the taking of Cynthia Ann Parker.

The story begins in the 1850s on the grassy prairies west of Fort Worth. During that turbulent decade Comanche and Kiowa people on one side and Anglo settlers supported by federal troops, Texas Rangers, and citizen militia groups on the other fought throughout the region, battling over land, livestock, wild game, and rights of occupation. In short, they struggled for control of the large area.

Defined as the region south of the Red River, west of Fort Worth, north of modern Interstate Highway 20, and east of the hundredth meridian, Northwest Texas during the period included what would become approximately twenty counties. Much of the Indian-white antagonism occurred in what are present-day Palo Pinto, Young, Jack, Parker, Stephens, Clay, Archer, and Wichita counties. In the early 1850s the hilly, well-watered, but sometimes drought-stricken prairie country was rich in grass and game, including deer, antelope, and bison. The Red and Brazos rivers, especially the Brazos, and their tributaries drained most of the region. The upper Trinity River, particularly its Clear Fork, drained some eastern parts of the area. Soils in Northwest Texas ranged from sandy loam to gray, black, and red. In 2010 the region remained largely rural, with cattle and horse raising important livelihoods. Crop agriculture included wheat, hay, oats, grain sorghums, and cotton.

Before the 1850s Northwest Texas was a mobile hunting society's paradise. In some ways it was the private hunting preserve of the Comanches and any guests they might indulge. Comanches, Kiowas, and other Indian groups for generations had traveled through, hunted across, lived in, and fought over the region. But now in the 1850s white Texans, farmers mainly, began moving their livestock and farming equipment into the area, threatening the region's hunting potential by disrupting bison herds and tilling up grass. As a result, Indian groups, especially such hunting tribes as the Comanches and Kiowas, found their territory threatened.

The problems were complicated. Through several generations Comanches and others had occupied the area and relied on its rich hunting potential for a livelihood. For reasons both economic and cultural, Comanches could not tolerate the advance of Anglo settlers into their traditional homeland. Conversely, white farmers, ranchers, and towns-people regarded Comanche and Kiowa hunting bands as hostile intruders without legitimate rights to the region.

At the same time, several other issues pressed against the Comanches. A decline in bison numbers, with resulting food shortages; contraction of their land base; and depopulation from disease and warfare were among them. In fact, after the War with Mexico ended in 1848, all of Comanchería seemed threatened. In Indian Territory (Oklahoma), various well-armed eastern tribes, such as the Osages, pressured the northeastern Comanche divisions. The Fort Smith–Santa Fe Trail cut east and west though the heart of the huge Comanche territory in the Texas Panhandle, and the Cimarron Cutoff of the older Santa Fe Trail further carved up Comanchería. A north-south string of federal forts—Belknap, Phantom Hill, Chadbourne, Concho, McKavett, Terrett, and Clark—built in 1851 and afterward through western Texas from the Red River to the Rio Grande encouraged white settlers to push up against southern Comanchería. In 1853 the federal government negotiated the Fort Atkinson treaties that restricted the reach of the Comanches and other Southern Plains Indians. Beginning in 1858 the Colorado gold rush destroyed once lush hunting grounds in the upper Arkansas River country.12

Indeed, the decade of the 1850s represents something of a turning point in Comanche political and economic history. For one thing, the federal government, as in the 1853 Fort Atkinson treaty, was urging Comanches to end their forays into Mexico, thus threatening a source of livelihood and restricting Comanche economic activities. For another thing, the federal military became more aggressive, launching a whole series of offensive operations against Native American home-lands. Then, government authorities moved to establish a reservation in Texas, further restricting Comanche hunting, travel, and independence in the state.

Faced with such pressures and confronted by declining bison numbers and concomitant food shortages, Comanches adjusted their raiding practices. Once used to expand territory, to ensure safety through aggression, to gain glory and honor, or to seek revenge, raiding became an economic necessity. Comanches stole horses, cattle, equipment, and other goods, including food, and traded some of it to Comancheros from New Mexico for items tribal members needed. Sometimes Native Americans traded their kidnapped victims. Favorite Comanche-Comanchero trading sites existed in canyons up and down the eastern caprock escarpment of the Llano Estacado.

Comanches were not the only raiders in Northwest Texas. Recent scholarship suggests some, perhaps much, of the supposed Comanche raiding activity was actually the dirty work of white thugs, desperados, and thieves falsely identified as Native Americans.13 Regardless, whites struck back against Indians, attacking Comanche, Kiowa, and Wichita camps in Texas. They even raided Indian villages located north of the Red River in Indian Territory, a region outside the jurisdiction of Texas state troops.

With a view to ending the conflicts and perhaps treating Native Americans fairly, the federal government stepped in. The Fort Atkinson Treaty, among other things, provided food and clothing to Comanches. In Northwest Texas the federal government established two reservations. One housed Wichitas, Tonkawas, Caddoes, and others deemed “friendly.” Their reserve, the Lower or Brazos Indian Reservation, of about 37,000 acres, opened in 1855 just below the junction of the Clear and Salt forks of the Brazos River in Young County. The second reservation housed at first about 277 Texas Comanches (Penatekas), but its population soon increased to over 500. Their reserve of 22,000 acres, the Upper or Comanche Reservation, stood some forty-five miles farther west along the Clear Fork of the Brazos near the boundary of modern Shackelford and Throckmorton counties. It also opened in 1855, and the federal government located Camp Cooper there.14 Major Robert S. Neighbors, who had helped survey sites for the reserves, became the government's supervisor for the twin projects. Shapley P. Ross, the father of Sul Ross and a former Texas Ranger, became agent at the Lower Reservation, and John R. Baylor, a former state legislator and lawyer, was agent for the Upper Reservation before authorities in 1857 replaced him with Matthew Leeper.

The reservations did little to stop Indian and Anglo difficulties in Northwest Texas. Raids and counterattacks continued. Murder, kidnapping, and theft often occurred when Indians or white thugs raided ranc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 - Background

- 2 - The Sources

- 3 - The Reports

- 4 - The Reminiscences

- 5 - Peta Nocona

- 6 - Conclusion

- Notes

- Appendix: A Chronology of Participant and Eyewitness Accounts

- Bibliography

- Index