eBook - ePub

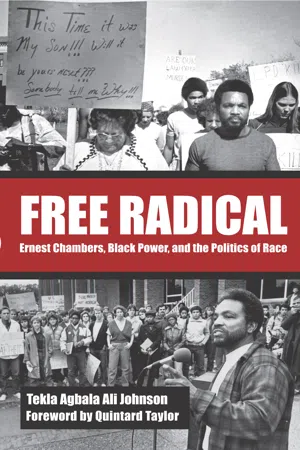

Free Radical

Ernest Chambers, Black Power, and the Politics of Race

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Amid the deadly racial violence of the 1960s, an unassuming student from a fundamentalist Christian home in Omaha emerged as a leader and nationally recognized black activist. Ernest Chambers, elected to the Nebraska State Legislature in 1970, eventually became one of the most influential legislators the state has ever known. As Chambers bids for reelection in 2012 to the office he held for thirty-eight years, Omaha native Tekla Agbala Ali Johnson illuminates his embattled career as a fiercely independent self-styled "defender of the downtrodden."Tracing the growth of the Black Power Movement in Nebraska and throughout the U.S., Ali Johnson discovers its unprecedented emphasis on electoral politics. For the first time since Reconstruction, voters catapulted hundreds of African American community leaders into state and national political arenas. Special-interest groups and political machines would curb the success of aspiring African American politicians, just as urban renewal would erode their geographical and political bases, compelling the majority to join the Democratic or Republican parties. Chambers was one of the few not to capitulate.In her revealing study of the man and those he represented, Ali Johnson portrays one intellectual's struggle alongside other African Americans to actualize their latent political power.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Free Radical by Tekla Agbala Ali Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1—Education of a Radical

I’m just a Barber, that’s all. I’m just a person who lives and works down here in the ghetto, and everyday I see people who are hurting. I see children who don’t have what they need in the way of clothing and food and educational opportunities…. Our people are just too concerned about getting the necessities to stay alive. They can’t be dreamers or poets.

—“Ernie Chambers,” Black and White: Six Stories from a Troubled Time

A visitor named Theopholis X was standing on a street corner in downtown Omaha one March afternoon. He was wearing a business suit and tie and selling issues of the Nation of Islam’s newspaper, Muhammad Speaks. Mr. X was questioned about his work and ultimately beaten by two police officers and by white bystanders, and taken to jail. Before nightfall, “Ernie” Chambers, a young barber-activist was downtown at the Detective Bureau demanding to know why Mr. X had been arrested. He learned that no charges had been filed, although Mr. X was continuing to be held. Chambers told Mayor A. V. Sorensen that Mr. X was a victim of police misconduct. The mayor said that one officer had suffered minor injuries. Chambers said that, if so, he might have hurt himself in his haste to draw his pistol from its holster. Selling papers is not a crime, Chambers told the mayor; the officers exceeded their authority when they grabbed the man. “How predictable,” he wrote, “that the police chose the first warm day to renew hostilities against the African community. If there is a trial on this matter, be prepared to defend every act of the police along with the failure to charge Theopholis X with any violation justifying arrest.” Chambers’s two years in law school were paying off. He knew how the law worked and was able to make it clear to the County Attorney that if charges were filed against Mr. X, the city would have to contend with him.1

Rural communities speckle an otherwise agricultural landscape, separating prairie grasses that swoon in summer and autumn under a gusty midwestern breeze. Almost anyone born in the state can distinguish Nebraska blindfolded: its icy winters; in warm weather, its sure-welcoming earth under bare feet, the scent of sweet grass, the shaking tassels of corn before a mid-summer’s storm; and on hot sunny days, its sea of dark green stalks under a stark blue sky. The expansiveness of the countryside, unbroken by trees or hills, is so vast that it gives one a sense of timelessness. Townsfolk in Fremont, Norfolk, Grand Island, Hastings, Kearney, North Platte, Bellevue, Lincoln, and Omaha are able to experience the beauty of the Great Plains along with the comforts of the city. Whatever one’s vantage point in Nebraska, it is impossible to miss the vitality of the region, blessed by Mother Nature with fertility and grace. But, to African Americans who venture here, the white inhabitants (and the stoic countenances many of them turn toward anyone who is not of Northern European extraction), seem out of place. No matter how hard African Americans confined to segregated North Omaha might have tried to imagine European immigrants as natural to the environs, as a group, white people’s racialized approach to life failed to match the serenity and calm of the natural scenes.

For as far back as Ernest Chambers could remember, black people in the urban Midwest had experienced hostility from whites. Nebraska had been a free state in the years leading up to the American Civil War and a harbor for Africans fleeing from slavery. But the state’s majority population was conflicted about how to engage with free African Americans. Lynching occurred in several of the state’s largest cities and towns. A KKK convention drawing 25,000 participants was held in Lincoln around the time the Chambers family came to Nebraska. Chambers’s grandparents had migrated from West Point, Mississippi, during the second decade of the twentieth century. The fourth child of Malcolm Chambers of Omaha, and Lillian (Swift) Chambers of Rayville, Louisiana, he was christened Ernest William Chambers at his birth on July 10, 1937. Malcolm, a packinghouse worker who also preached the gospel, and Lillian, a homemaker, eventually became the parents of seven children—three girls (Nettye, Alyce, and JoAnn) and four boys (Ernest, Robert, Eddie, and Gilbert).

Whatever their ethnic or racial background, most immigrant populations in Nebraska describe themselves as possessing a certain uniqueness of character resulting from the experiences of their ancestors, black or white, on the “frontier.” It is widely held among Nebraskans that they are a hardworking, pragmatic people. That Nebraskans share some ideals which set them apart from people in other regions of the county is not entirely fanciful. They differ from east coast and west coast Americans in ways that can be quantified by examining their priorities and preferences as exemplified through their voting records. For example, for more than a decade Nebraskans have approved state budgets that spend a third less per capita on public education, a full three-fourths less on intergovernmental agencies, and more than one-fifth less on public welfare than approved by the majority populations of other states. However, they spend significantly more on highways and somewhat more on postsecondary education. They also show a preference for small government. But this is revealed in curious ways, like the fact that Nebraska’s state senators enjoy one of the lowest salaries for state legislators in the nation, and are paid about $12,000 in annual wages. It might be safely argued that the citizens of Nebraska have the most in common politically with the populations of other agricultural states.2

That his community was separated from the predominately white sections of the city was a fact of life that Chambers learned along with other basic instruction that African American children living in urban Omaha in the 1940s received at home. Later, he discovered that his neighborhood terrified whites, whose fears of blacks bordered on paranoia. These feelings were derived from the homogeneity of their neighborhoods and a phobia of the unknown. The Near Northside, as Chambers’s community was often called, also suffered because of bad relations with the local police force. Although domestic servants, members of the clergy, and other elite blacks were sometimes exceptions, as a group African Americans were socially ostracized by most of the state’s ninety-plus percent of the population. Chambers was an extremely shy and quiet boy. No one guessed that he would grow up to be the defender and undisputed leader of Nebraska’s African American population, and the most powerful legislator the state had ever seen.

As hard as the Great Depression was on white communities, it was even more devastating to North Omaha, a community of about 14,000 (about one-tenth the population of Omaha proper). Chambers’s family felt the strain of limited capital and, like most everyone else, responded with increased resourcefulness. Some families’ straits were ameliorated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, which provided public works jobs for the unemployed. On the whole, though, African Americans’ financial problems were lessened only with the outbreak of the Second World War. The war provided an unprecedented number of black men and black women jobs in the armaments industry.

Meanwhile, with the exception of his all-white teachers and his white classmates, Chambers’s world was largely segregated. For more than twenty years, one Catholic priest, Father John Markoe of Creighton University, challenged Omaha’s discriminatory customs. Markoe helped to organize the De Porres Club, a group of African American pastors, community leaders, and young people who advocated for equal rights. The members also formed the Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties (4CL) to hold watch at city council meetings and record the proceedings. The group condemned segregation in Catholic schools and demonstrated against the Coca-Cola Bottling plant, the Greyhound bus station, Eppley Airfield, and local hotels, all of which refused to employ or to provide service to African Americans. As early as 1948, Omahans demonstrated publicly against housing and job discrimination. The St. Martin De Porres Center would for decades remain a hub of local activism and the site of a chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE).3

North Omaha had its own culture and economy with black-owned businesses and others that belonged to Russian and Jewish immigrants. There were numerous storefront churches. National Urban League chapters in Lincoln and Omaha, Nebraska’s largest cities, held adult education and self-help seminars and sponsored health, recreation, and job programs. Many of the programs open to black youth during Chambers’s childhood were organized by the NAACP, the Omaha Urban League, and the Culture Center in South Omaha, which provided a separate facility for blacks to supplement the segregated Social Settlement House. (The Culture Center later became known as Woodson Center.4) The Urban League tried to negotiate with city leaders to provide African Americans use of a swimming pool in Florence, the neighborhood just to the north, but was refused. It also took on housing discrimination, which turned out to be a battle that would continue for another generation.5

Excluded from white clubs and restaurants, African Americans developed their own high society and night life in Omaha. A favorite event of many of Chambers’s age mates by late adolescence was the Coronation Ball, held each year at Cecilia and James Jewells’ Dreamland Hall on North 24th Street. There the crowds celebrated the crowning of King Borealis and Queen Aurora. This was likely a transformation of traditional African forms of socio-political organization, which emerged in many segregated communities of diasporic Africans. For technical musical training, African American youngsters attended Florence Pinkston’s School of Music. Anyone in need of cab service could phone the Sunset Taxicab Company owned by community member Frank James. Later the Ritz and United Cab Companies replaced Sunset as black-owned taxis. When demand for rides increased and white taxi companies refused to service the area, jitney services provided by men driving their own cars out of a jitney stand became popular in Omaha. The community also boasted six black-run grocery stores, two pharmacies, furniture and music stores, eight barbershops, three real-estate offices, eight restaurants, and seven bars. Carpentry, contracting, and plumbing were lucrative ventures for African American business owners—with nearly exclusively African American clientele—and Shipman Brothers Road Building Company was especially successful. Proud of African people’s progress, local historian H. J. Pinkett said that African Americans had been nearly 100 percent illiterate in 1865, but by the 1930s there was only four percent illiteracy in the segregated section of the city. Some North Omahans sent their children to be educated at Howard University and other well-known schools. However, most community members worked as unskilled or semi-skilled laborers or in trades. During this era, barbershops were the political and intellectual equivalents of Irish pubs or the soapboxes on Boston Common. There, men gathered and debated relevant topics of the day while youngsters learned about things they did not hear much about at home. Prominent barbers in Omaha in the 1930s and 1940s were R. C. Price, E. W. Killingworth, C. B. Mayo, Richard Taylor, P. M. Harris, C. H. Rucker, and W. H. Taylor. Chambers later recalled going to C. B. Mayo’s place as a boy. Mayo, he said, was a grouchy old man who used to cut his hair in a bowl shape...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Also in Plains Histories

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Plainsword

- Prologue

- Introduction

- 1 Education of a “Radical”

- 2 Man of the People

- 3 Grounded Politician

- 4 The Power of One

- 5 Statecraft

- 6 “Defender of the Downtrodden”

- 7 “Dean”

- Afterword

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author