Chapter One

Warren Buffett

Berkshire Hathaway

Warren Buffett is the dean of shareholder cultivation and prince of the shareholder letter. Buffett consciously embraced the need for such outreach when running his partnership, beginning in 1956. He committed considerable effort to it from the 1970s, after taking the helm at Berkshire Hathaway, a public company. The 1978 letter was the first masterpiece and since then, to the present, Buffett’s annual letters have stood above all others as the most influential.12

As the gold standard in the shareholder letter genre, people wonder what most distinguishes Buffett’s annual missive to Berkshire shareholders. Clarity, wit and rationality are hallmarks to emulate, along with how Buffett personally pens lengthy sections to read more as literary essays than corporate communications.

But these attractive qualities are products of a deeper distinction that holds the greatest value. Every Buffett communiqué has a particular motivation: to attract shareholders and colleagues—including sellers of businesses—who endorse his unique philosophy. Tenets include fundamental business analysis, old-fashioned valuation methods, and a long time horizon.

A recurring motif of Buffett’s writing is the classic rhetorical practice of disagreement. Buffett recites conventional wisdom along with multiple reasons why it is inaccurate or incomplete. He then differentiates Berkshire with themes like autonomy, permanence, and trust.

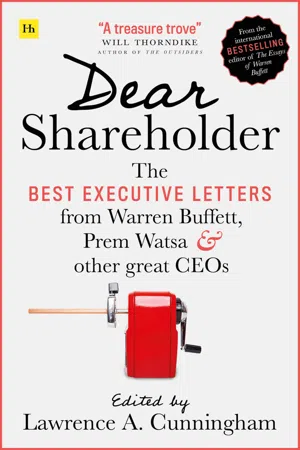

A popular way to study these gems is my annotated collection, The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America. The selections that follow, drawn from that collection, concentrate solely on the most salient examples of Buffett’s portrait of his company, as one catering to long-term committed owners. After explaining why he chose that profile, topics include stock splits, dividends and share buybacks, stock market listings and spreads, and Berkshire’s dual class recap. Selections appear, as with most other essays in this book, not in thematic sequence but in chronological order.

1979

Seeking Quality

In some ways, our shareholder group is a rather unusual one, and this affects our manner of reporting to you. For example, at the end of each year about 98% of the shares outstanding are held by people who also were shareholders at the beginning of the year. Therefore, in our annual report we build upon what we have told you in previous years instead of restating a lot of material. You get more useful information this way, and we don’t get bored.

Furthermore, perhaps 90% of our shares are owned by investors for whom Berkshire is their largest security holding, very often far and away the largest. Many of these owners are willing to spend a significant amount of time with the annual report, and we attempt to provide them with the same information we would find useful if the roles were reversed.

In contrast, we include no narrative with our quarterly reports. Our owners and managers both have very long time-horizons in regard to this business, and it is difficult to say anything new or meaningful each quarter about events of long-term significance.

But when you do receive a communication from us, it will come from the fellow you are paying to run the business. Your Chairman has a firm belief that owners are entitled to hear directly from the CEO as to what is going on and how he evaluates the business, currently and prospectively. You would demand that in a private company; you should expect no less in a public company. A once-a-year report of stewardship should not be turned over to a staff specialist or public relations consultant who is unlikely to be in a position to talk frankly on a manager-to-owner basis.

We feel that you, as owners, are entitled to the same sort of reporting by your managers as we feel is owed to us at Berkshire Hathaway by managers of our business units. Obviously, the degree of detail must be different, particularly where information would be useful to a business competitor or the like. But the general scope, balance, and level of candor should be similar. We don’t expect a public relations document when our operating managers tell us what is going on, and we don’t feel you should receive such a document.

In large part, companies obtain the shareholder constituency that they seek and deserve. If they focus their thinking and communications on short-term results or short-term stock market consequences they will, in large part, attract shareholders who focus on the same factors. And if they are cynical in their treatment of investors, eventually that cynicism is highly likely to be returned by the investment community.

Phil Fisher, a respected investor and author, once likened the policies of the corporation in attracting shareholders to those of a restaurant attracting potential customers. A restaurant could seek a given clientele—patrons of fast foods, elegant dining, Oriental food, etc.—and eventually obtain an appropriate group of devotees. If the job were expertly done, that clientele, pleased with the service, menu, and price level offered, would return consistently. But the restaurant could not change its character constantly and end up with a happy and stable clientele. If the business vacillated between French cuisine and take-out chicken, the result would be a revolving door of confused and dissatisfied customers.

So it is with corporations and the shareholder constituency they seek. You can’t be all things to all [people], simultaneously seeking different owners whose primary interests run from high current yield to long-term capital growth to stock market pyrotechnics, etc.

The reasoning of managements that seek large trading activity in their shares puzzles us. In effect, such managements are saying that they want a good many of the existing clientele continually to desert them in favor of new ones—because you can’t add lots of new owners (with new expectations) without losing lots of former owners.

We much prefer owners who like our service and menu and who return year after year. It would be hard to find a better group to sit in the Berkshire Hathaway shareholder “seats” than those already occupying them. So we hope to continue to have a very low turnover among our owners, reflecting a constituency that understands our operation, approves of our policies, and shares our expectations. And we hope to deliver on those expectations.

1983

Stock Splits

We are often asked why Berkshire does not split its stock. The assumption behind this question usually appears to be that a split would be a pro-shareholder action. We disagree. Let me tell you why.

One of our goals is to have Berkshire Hathaway stock sell at a price rationally related to its intrinsic business value. (But note “rationally related,” not “identical”: if well-regarded companies are generally selling in the market at large discounts from value, Berkshire might well be priced similarly.) The key to a rational stock price is rational shareholders, both current and prospective.

If the holders of a company’s stock and/or the prospective buyers attracted to it are prone to make irrational or emotion based decisions, some pretty silly stock prices are going to appear periodically. Manic-depressive personalities produce manic-depressive valuations. Such aberrations may help us in buying and selling the stocks of other companies. But we think it is in both your interest and ours to minimize their occurrence in the market for Berkshire.

To obtain only high quality shareholders is no cinch. Mrs. Astor could select her 400, but anyone can buy any stock. Entering members of a shareholder “club” cannot be screened for intellectual capacity, emotional stability, moral sensitivity or acceptable dress. Shareholder eugenics, therefore, might appear to be a hopeless undertaking.

In large part, however, we feel that high quality ownership can be attracted and maintained if we consistently communicate our business and ownership philosophy—along with no other conflicting messages—and then let self selection follow its course. For example, self selection will draw a far different crowd to a musical event advertised as an opera than one advertised as a rock concert—even though anyone can buy a ticket to either.

Through our policies and communications—our “advertisements”—we try to attract investors who will understand our operations, attitudes and expectations. (And, fully as important, we try to dissuade those who won’t.) We want those who think of themselves as business owners and invest in companies with the intention of staying a long time. And, we want those who keep their eyes focused on business results, not market prices.

Investors possessing those characteristics are in a small minority, but we have an exceptional collection of them. I believe well over 90%—probably over 95%—of our shares are held by those who were shareholders of Berkshire five years ago. And I would guess that over 95% of our shares are held by investors for whom the holding is at least double the size of their next largest. Among companies with at least several thousand public shareholders and more than $1 billion of market value, we are almost certainly the leader in the degree to which our shareholders think and act like owners. Upgrading a shareholder group that possesses these characteristics is not easy.

Were we to split the stock or take other actions focusing on stock price rather than business value, we would attract an entering class of buyers inferior to the exiting class of sellers. Would a potential one-share purchaser be better off if we split 100 for 1 so he could buy 100 shares? Those who think so and who would buy the stock because of the split or in anticipation of one would definitely downgrade the quality of our present shareholder group.

(Could we really improve our shareholder group by trading some of our present clear-thinking members for impressionable new ones who, preferring paper to value, feel wealthier with nine $10 bills than with one $100 bill?) People who buy for non-value reasons are likely to sell for non-value reasons. Their presence in the picture will accentuate erratic price swings unrelated to underlying business developments.

We will try to avoid policies that attract buyers with a short-term focus on our stock price and try to allow policies that attract informed long-term investors focusing on business values. Just as you purchased your Berkshire shares in a market populated by rational informed investors, you deserve a chance to sell—should you ever want to—in the same kind of market. We will work to keep it in existence.

One of the ironies of the stock market is the emphasis on activity. Brokers, using terms such as “marketability” and “liquidity”, sing the praises of companies with high share turnover (those who cannot fill your pocket will confidently fill your ear). But investors should understand that what is good for the croupier is not good for the customer. A...