![]()

1

The Art and Faculty of Playing: The King’s Men and Their Roles

One of the earliest histories of the English stage, James Wright’s 1699 book Historia Histrionica, is also a history of the King’s Men, the actors that made up the company in successive decades, and the roles that they took. The book takes the shape of a dialogue, in which a Restoration playgoer, Lovewit, questions an older man, Truman, about the actors of the period before the Civil War. Early in their conversation, Lovewit laments the fact that earlier printed plays do not carry ‘the Actors Names over against the Parts they Acted’, because if they had ‘one might have guest at the Action of the Men, by the Parts which we now Read in the Old Plays’ (Wright 1699: 3). Truman comments that some early plays indeed carry such information, listing among them five plays of the King’s Men, and under Lovewit’s questioning he also describes in some detail the leading actors of the 1630s and early 1640s:

in my time, before the Wars, Lowin used to Act, with mighty Applause, Falstaffe, Morose, Vulpone, and Mammon in the Alchymist; Melancius in the Maid’s Tragedy, and at the same time Amyntor was Play’d by Stephen Hammerton, (who was at first a most noted and beautiful Woman Actor, but afterwards he acted with equal Grace and Applause, a Young Lover’s Part) Tayler Acted Hamlet incomparably well, Jago, Truewit in the Silent Woman, and Face in the Alchymist; Swanston used to Play Othello: Pollard, and Robinson were Comedians, so was Shank who used to Act Sir Roger, in the Scornful Lady. These were of the Blackfriers. Those of principal Note at the Cockpit, were, Perkins, Michael Bowyer, Sumner, William Allen, and Bird, eminent Actors. and Robins a Comedian. Of the other Companies I took little notice.

(4)

Truman offers tantalizing glimpses of these players in action. He recalls the physically imposing John Lowin, who not only inherited roles such as Falstaff, the manipulative, malingering Volpone in Ben Jonson’s play of that title – a role originally played by Richard Burbage – and the grotesquely noise-intolerant Morose in Jonson’s Epicoene, but also created Sir Epicure Mammon in The Alchemist and the regicidal war hero Melantius in Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher’s The Maid’s Tragedy.1 Lowin’s closest colleague, Joseph Taylor, is brought to mind in a series of roles that he inherited from other actors: Hamlet, Iago, the mouthy gallant Truewit in Epicoene and the servant-turned-conman Face in The Alchemist. The glamorous Stephen Hammerton is remembered as the wavering Amintor in The Maid’s Tragedy, and another leading performer, Elliard Swanston, is recalled as Othello. Truman also recollects comic actors such as Thomas Pollard, William Robins (also known as Robinson) and John Shank, who played the parson Sir Roger in Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Scornful Lady.

Some of the actors that Wright associates with the Cockpit also performed with the King’s Men. Richard Perkins was with them around 1622–5, before leaving for a new company under the patronage of Queen Henrietta Maria, with which he spent the rest of his career. The others became King’s Men at the high point of their acting lives: Michael Bowyer and William Allen appear to have joined the company around 1637, followed by Theophilus Bird at some point between May 1638 and August 1639; William Robins was with them by 1641, and most likely a few years earlier. In addition to his account of Hammerton’s career, Truman provides further information about the actors who played female and juvenile roles, such as the famous Restoration actors Charles Hart and Walter Clun, who ‘were bred up Boys at the Blackfriers; and Acted Womens Parts, Hart was Robinson’s Boy or Apprentice: He Acted the Dutchess in the Tragedy of the Cardinal, which was the first Part that gave him Reputation’ (3).

Wright’s book offers an account of the King’s Men that is incomplete and fragmented – giving us only partial insights into long careers – but it also provides a long view of the company’s internal structures, its personnel, parts and performances. His narrative brings to the fore such issues as the existence of different ranks and specialisms within the company, the variety of interactions that existed between actors, the styles of performance and techniques that they employed and the range of roles that an individual performer might present. It also underscores the crucial function of spectators, who experience and remember individual actors and performances, and it creates in the process a submerged history of a family of playgoers. Wright, who was born in 1643, apparently draws on the memories of his father, Abraham, born in 1611, whose manuscript transcriptions of extracts from plays that he saw or read around 1640, and his notes on them, were preserved by his son.2

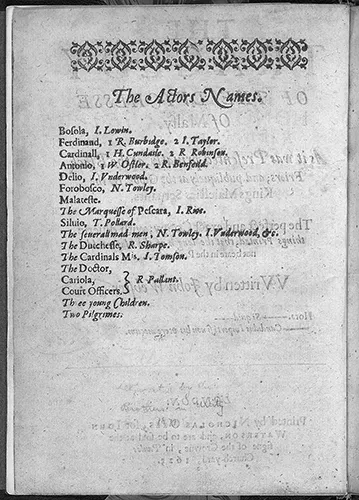

Truman’s recollections of the actors and their roles offers a good deal of Shakespearean material, but the same cannot be said of other forms of evidence. The central performers and casting practices of the King’s Men are uniquely well documented in comparison with their contemporaries, but one thing is notable for its absence. Although tiny fragments of casting information survive in printed texts of plays such as Romeo and Juliet, Much Ado About Nothing and The Two Noble Kinsmen (Shakespeare 1599: K3v; 1600: G3v–G4v; Shakespeare and Fletcher 1634: I4v, L4v), we have yet to discover any manuscript or printed source that provides comprehensive information about the casting of a Shakespeare play. Instead, we have to look at the rich materials that do survive for the plays of his contemporaries and successors. A series of plays include detailed cast-lists that attribute roles to individual actors. Five of them are mentioned by Truman in Historia Histrionica: John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi (Figure 3), which presents the casts of an early performance around 1613 and a revival around 1620–3; Philip Massinger’s The Roman Actor, performed in 1626, and The Picture, performed in 1629; Lodowick Carlell’s The Deserving Favourite, performed around 1629; and Fletcher’s The Wild Goose Chase, which presents the cast of a revival around 1632.3 We now also know, as Truman did not, that similar cast-lists appear in manuscript copies of John Clavell’s The Soddered Citizen (c. 1630) and Arthur Wilson’s The Swisser (1631), and that actors’ names appear in the stage directions and other parts of the playhouse manuscripts of Middleton’s The Second Maiden’s Tragedy (1611), Fletcher and Massinger’s Sir John Van Olden Barnavelt (1619) and Massinger’s Believe As You List (1631).4 Moreover, the ‘plot’ of the second part of The Seven Deadly Sins, a playhouse document that tracks the entrances, exits and stage business for the purposes of managing a performance, includes the names of most of the members of the Chamberlain’s Men – the predecessors of the King’s Men – around 1597–8.5

FIGURE 3 ‘The Actors Names’, in The Tragedy of the Dutchesse of Malfy (London, 1623), General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

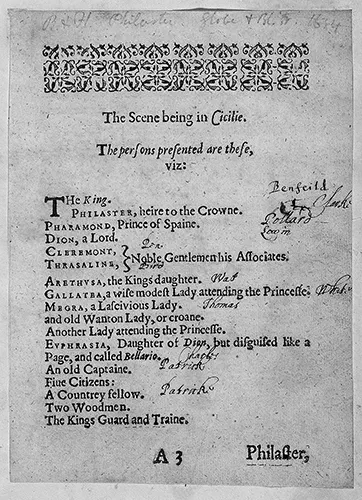

In contrast with the 1623 folio edition of Shakespeare’s plays, which presents a single list of ‘The Names of the Principall Actors in all these Playes’ – a list headed by Shakespeare himself – the 1616 folio of Jonson’s Works and the 1679 second folio of the Comedies and Tragedies of Fletcher and his collaborators include lists of the names of the principal actors in individual plays. A more detailed actor-list was also printed with the quarto edition of John Ford’s The Lover’s Melancholy, performed by the King’s Men in 1628 and printed in 1629 (A1v). Although these texts do not assign roles to individual actors, seventeenth-century readers sometimes added this information. For example, the owner of a copy of the Jonson folio wrote actors’ names against some of its character-lists and character names against some of its actor-lists, providing detailed information about the casts of revivals of Volpone and The Alchemist around 1616–18.6 Similarly, the owner or owners of a copy of the 1634 quarto of Beaumont and Fletcher’s Philaster wrote the names of the actors against those of the characters (see Figure 4).7

FIGURE 4 ‘The persons presented’, with manuscript annotations, in Philaster (London, 1634), Art Inv. 271 no. 10e (2). Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

These sources shed a good deal of light on the casting practices and performances of the King’s Men. They help us to track arrivals and departures; the roles and perceived characteristics of different groups of actors, such as leading men, comic specialists and the trainee players who performed female and juvenile roles; and the structures through which the company ran and maintained itself. All of these events, processes and conventions factored into the practices of the King’s Men, and they shed light on the ways in which the company shaped the stage-lives of Shakespeare’s plays, from the way that the company’s composition shaped their patterns of new commissions and revivals, to the ghostly interactions between actors and roles that helped to structure spectators’ responses.

Leading men

The surviving sources document successive generations of the leading performers in the King’s Men. A constant presence throughout is John Lowin, who seems to have joined the company from Worcester’s Men in 1603 or early 1604 (Syme 2019a: 239–40), perhaps as a replacement for Thomas Pope. Lowin was in his mid-twenties at this time, eight years younger than Richard Burbage, who was firmly established as the company’s leading actor. One of the earliest actor-lists for a King’s Men play, printed with Jonson’s Sejanus (1616: 2O3v), is headed by Burbage, who probably played the title role. Lowin, who is the seventh of the eight actors named, appears to have taken a supporting role in Jonson’s tragedy – perhaps playing Silius, as Thomas Whitfield Baldwin thought (1927: casting chart between pages 434 and 435), or Macro, as Shoichiro Kawai has more recently argued (1992: 26). However, he quickly rose to prominence within the company, perhaps in part as a result of the death of Augustine Phillips in May 1605, and he appears in a list of the sharers compiled in late 1607.8 He played the demanding part of the disturbed and manipulative serving-man Bosola in The Duchess of Malfi, and his roles of Eubulus in The Picture and Dion in Philaster – both of which are variations on the early modern stock character of the loyal but outspoken courtier – are among the largest in these plays. His known Shakespearean roles include Iago, Falstaff (a role that he may have picked up from William Kemp or Pope), and King Henry in Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Henry VIII, or All is True. Alongside these more serious roles, the fact that he was renowned for playing Falstaff, Epicure Mammon, Sir Politic Would-Be and the bashful would-be lover Belleur in The Wild Goose Chase suggests his ability to play comedy effectively. It is, therefore, perhaps unsurprising to find a prologue apparently written for Lowin to speak before William Davenant’s 1635 play The Platonic Lovers, in which the actor describes himself to the audience as ‘I (your Servant) who have labour’d here / In Buskins, and in Socks, this thirty year’ (1636: A3r). The prologue’s references to the buskins conventionally worn by tragedians in classical theatre and the socks worn by comedians pay tribute to Lowin’s versatility.

A similar versatility was required of Burbage, who heads the actor-lists in all of the plays of Jonson in which he appeared and features prominently in all of the surviving Fletcherian actor-lists for plays performed by the King’s Men during his lifetime. He probably continued acting until not long before his death on 13 March 1619, as he features in the list of the leading actors in Fletcher’s The Loyal Subject (Beaumont and Fletcher 1679: 2K4r), licensed by the Master of the Revels on 16 November 1618 (Bawcutt 1996: 185). His known roles include King Gorboduc and the rapist Tereus in the second part of The Seven Deadly Sins (c. 1597–8), Shakespeare’s Richard III, Volpone, Subtle in The Alchemist and Ferdinand in The Duchess of Malfi. Other roles are listed in an elegy that commemorated his death:

hees gon, & wth him what a world is dead?

by him reuiu’d, now to obliuion goe,

no more young Hamlett, old Hieronimo

Kinge Leer, the greeu’d Moore; & more besides

(that liued in him) are now for euer dead.9

This elegy is attributed in one manuscript – the one from which I quote here – to John Fletcher, a former collaborator of Shakespeare who by 1619 had taken his older colleague’s place as the most regular playwright for the King’s Men. It thus marks a series of interactions within the company: between Shakespeare and Burbage, who gave life to his roles, between Shakespeare and Fletcher, and between Burbage and Fletcher. Moreover, it also points to the ways in which Shakespeare’s roles existed in dynamic tension with those of other playwrights, here captured in the juxtaposition of ‘young Hamlett’ and ‘old Hieronimo’, the revenging father of Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy.

Despite the prominence of Burbage and Lowin, other actors challenged their hold over the company’s plays. William Ostler, who joined the King’s Men around 1609 after beginning his career with the Children of the Chapel, later the Children of the Queen’s Revels, is listed second after Burbage in three of the five actor-lists that survive from the early to mid-1610s (Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Captain and Fletcher’s Bonduca and Valentinian) and fourth in the other two (The Alchemist and The Duchess of Malfi). Another graduate from the Chapel/Queen’s Revels company, Nathan Field, played Face opposite Burbage’s Subtle in The Alchemist around 1616–18. Both of these actors died young, Ostler in 1614 and Field – who may have been recruited to replace him – in 1619 or 1620.

The deaths of Burbage and Field led to changes in the company’s casting patterns. Burbage was quickly replaced by Jose...