eBook - ePub

The Merchant of Venice: The State of Play

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Merchant of Venice: The State of Play

About this book

The Merchant of Venice is one of Shakespeare's most controversial plays, whose elements resonate even more profoundly in the current climate of rising racism, antisemitism, Islamophobia, anti-immigrant sentiment, queerphobia and right-wing nationalism. This collection of essays offers a 'freeze frame' that showcases a range of current debates and ideas surrounding the play. Each chapter has been carefully selected for its originality and relevance to your needs. Essays offer new perspectives that provide an up-to-date understanding of what's exciting and challenging about the play. Key themes and topics include:

· Race and religion

· Gender and sexuality

· Philosophy

· Animal studies

· Adaptations and performance history

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Merchant of Venice: The State of Play by M. Lindsay Kaplan, Ann Thompson,Lena Cowen Orlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism in Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘Lend it rather to thine enemy’: Accentuating Difference in The Merchant of Venice

A canal in Venice, a gondola with a monk who glares menacingly, a brief scenic location, ‘Venice, 1596’, a torch burning a Hebrew book and scroll and then a series of informative and interpretative statements:

Intolerance of the Jews was a fact of 16th Century life even in Venice, the most powerful and liberal city state in Europe.

By law the Jews were forced to live in the old walled foundry or ‘Geto’ area of the city. After sundown the gate was locked and guarded by Christians.

In the daytime any man leaving the ghetto had to wear a red hat to mark him as a Jew.

The Jews were forbidden to own property. So they practiced usury, the lending of money at interest. This was against Christian law.

And intercut with each screen, an illustrative visual: a lock slamming shut, a young red-hatted man attacked, a coin dropped into a hand. Al Pacino (Shylock), wearing a red hat, makes his way through a crowd of people on and around the Rialto bridge, while the monk in the gondola rails against usury and the crowd responds by throwing a man off the bridge into the canal. Another recognizable figure, Jeremy Irons, bumps into Pacino, who says ‘Antonio’; and Irons spits in his face, then walks away through the crowd. As Pacino wipes his face, the screen shot turns into the burning of holy Hebrew texts. The music, which at the beginning, featured a solo male voice in a Hebrew prayer, now turns to a Latin text, invoking ‘Dominus’, and in the next shot, we see Irons kneeling, crossing himself.

This extended opening sequence of the 2004 film directed by Michael Radford represents a series of tendencies in post-Second World War productions of The Merchant of Venice: the foregrounding of religious prejudice, the clear differentiation between Christians and Jews, the overt hostility (spitting has become a sadly familiar cliché), and beginning not with the words of the play but with a pre-show sequence that creates a particular world. These choices and the concomitant rethinking of Antonio, Portia and Jessica, as well as the deliberate unease that the opening generates, are features not only of the film but have also dominated major stage productions of the last seventy years.

Take, for example, the Royal Shakespeare Company’s (RSC) 1987 production, directed by Bill Alexander. There, on a stage of wooden planks, as if near a mooring for a Venetian gondola, and with a large yellow Mogen David scrawled on the back wall (as well as an elegantly Byzantine golden icon of the Virgin), two young men spat at a Jew, identified as such because of the yellow Mogen David on his shoulder. He hadn’t done anything to them, and so the very casualness of the gesture was noticeable. As the production went on, the attacks became more pointed, with a trio labelled in the prompt book as ‘freaks’ (the programme called them ‘citizens of Venice’) popping up to harass Shylock, even throwing stones at him, and, in the trial scene, alternating cheers at Gratiano’s attacks and jeers of ‘Jew, Jew’.

Both the Radford film’s beginning and the RSC production’s pre-show couldn’t come as a surprise to the audience, whether in the cinema or in the theatre; the warnings, on screen, or with the contrasting motifs on the upstage wall, were clear. By contrast, the 2015 production at Shakespeare’s Globe, directed by Jonathan Munby, gained much of its power through surprise. Musicians and singers in Renaissance costumes strode onto the Globe stage. Such an opening is certainly a familiar, even conventional, way for Globe productions to open. Actors wearing leather commedia-style masks appeared, and a white-and-gold-clad Cupid bounded onto a small white platform stage in the middle of the Globe’s larger stage, so we seemed to have ‘street theatre’, a small masque for Venice’s carnival time. The appearance of two more masked figures, also in white – a man and a woman (the lovers ‘shot’ by Cupid with his golden bow) – turned the first group of Globe musicians and dancers into Venetians enjoying the carnival, singing, dancing and creating an atmosphere of fun. When a man walked in, pulled off his mask, paused and walked off, as if unwilling to participate, no one on stage paid any attention (although, no surprise, he turned out to be Antonio) and the dancing continued. But when two other men marked as Jews, with distinctive red hats, and a small yellow circle on their gowns, came in and tried to cross the stage, each found himself blocked, and then attacked, pushed to the ground; one was viciously kneed and kicked, then spat upon. And then, as one of the Jews helped his companion to stand up, and both exited through the crowd standing in the Globe’s audience, the dancing and singing continued. By sending a variety of conflicting signals, the Globe’s production shocked its viewers by destabilizing them. The light-hearted, even stylized, comedy first shown became deeply disturbing, in part because it started in the audience’s ‘world’ before moving into the world of the play, in part because the dancing and singing continued even after the gratuitous violence.

Of course, not every production has an extended pre-show, but many productions have wanted to create a specific world for the play, especially those that choose a setting other than Renaissance Italy. That setting can be as minimal as the columns, archways and walls in the BBC Shakespeare (Bulman 1991: 10–11), where we come to know characters through their costumes, particularly the opulent fabrics worn by the Venetians as contrasted with the black robe of Shylock. One familiar opening for the play has been a table and chairs, whether in the bare space of The Other Place in Stratford (RSC, 1978; directed by John Barton) as Antonio, Salerio and Solanio met to talk, or in the elegant café (specified as Café Florian) for the National Theatre’s 1970 production directed by Jonathan Miller, where the white tablecloths, elaborate coffee service and an obsequious waiter made clear that these men had plenty of money to spend. Indeed, when the pre-show or the set doesn’t insist on religious prejudice, it usually creates a world of wealth and privilege. In the 1993 RSC production in Stratford (dir. David Thacker), the table and chairs for the play’s opening conversation were downstage left, but a huge metallic structure of poles and staircases dominated the upstage area, with desks and computer work-stations visible. We saw a contemporary work-place, stylized and elegant, but clearly signifying a world focusing on business concerns. Similarly, in the 1997 RSC production in Stratford (dir. Gregory Doran), the opening moments featured commercial ventures. On a dark Renaissance Venetian wharf, merchants and potential customers looked at one of the huge wrapped objects on stage, while a prostitute solicited customers. That production’s most vivid moment also threw – literally – money on stage, as Bassanio emptied a chest with 3,000 ducats; later, Philip Voss’s kneeling Shylock kept slipping on those coins as he tried to rise and leave the courtroom, his physical embarrassment embodying his emotional defeat.

Perhaps the most extended pre-show of recent times came in 2011 in Stratford’s newly redesigned Royal Shakespeare Theatre, where director Rupert Goold set the play in Las Vegas, and the opening scene in a casino. Here Antonio played cards, tourists in wildly awful clothes (from tacky flowered shirts to a long fur coat) sashayed around, and cocktail waitresses in high heels, short skirts and almost-backless tops served drinks and flirted with the customers. Chorus girls on the two curved staircases upstage heralded the arrival of an Elvis Presley impersonator, wearing a white suit studded with sequins, thrusting his hips, singing ‘Viva Las Vegas’ – the central roulette table rose up to become ‘Elvis’s’ stage. When Shakespeare’s lines finally were heard, they were spoken with American accents. Everything and almost everyone on stage seemed casual, careless, caught up in the meaningless glitz of the casino; Scott Handy’s pale Antonio, dressed in a blue blazer and blue trousers, was the least flashy person on stage, and in that way attracted our attention.

Such an elaborate opening raises the question: what is the point of a pre-show? I would contend that, like the interpretative screens at the beginning of the Radford film, the pre-show sequence offers the director a way to explain to the audience the context in which the actions of the play – if not justifiable – will, at least, make sense. Thus, the overt violence shown towards Jews at the beginning of the productions in 1987 and 2015 immediately let the audience know that these worlds divided people into abusers and victims, insiders and outsiders. Both of these productions chose time periods roughly contemporary with the play’s writing, just as the Radford film announced itself as set in Venice, 1596. By contrast, productions set in more recent time periods, especially those with nineteenth- and twentieth-century settings, seem less likely to stress overt antisemitism. Such productions – and here I think primarily of the 1970 National Theatre production and the 1993 RSC production, both of which showed Shylock as a prosperous banker – may gradually reveal antisemitic behaviour, but often that comes as a surprise to Shylock, as well as to the audience.

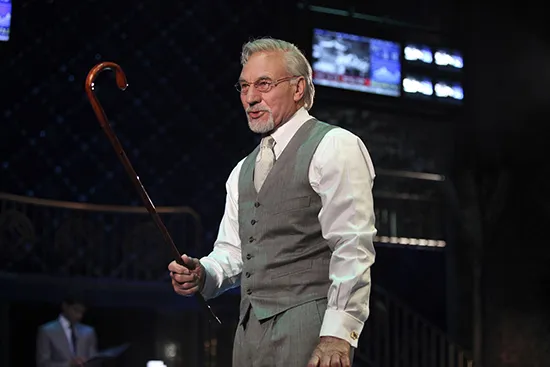

The Las Vegas setting might seem unrelated, certainly to antisemitism, and to the play; indeed, a number of reviewers felt that Rupert Goold’s choices were flashy and incoherent. Charles Spencer, in the Daily Telegraph, spoke of ‘director’s theatre run riot’ (2011), and Michael Billington, in The Guardian, began by admitting that he had ‘difficulty working out the logic of the setting: why, in particular, should Patrick Stewart’s multi-millionaire property-owning, semi-assimilated Shylock feel an “ancient grudge” towards the local Christians? And could we really believe they would void their spittle upon him in the wide streets of the US gambling capital?’ (2011). But Billington moved beyond his initial question to the idea that ‘wealth is no barrier against ingrained anti-semitism and Stewart’s Shylock, however comfortable he may seem, is secretly despised and he is reduced, presumably because denied access to the golf clubs, to trying a few putting shots in his office. And, the greater his sense of isolation, the more he (Shylock) reverts to his ancestral religion’ (2011: 530). Perhaps Stewart’s Shylock was isolated, but he was also elegant and confident, in a three-piece grey suit (subdued pinstripes), a silk tie, his neatly trimmed beard and glasses making him seem almost grandfatherly (see Figure 1). When he goes out to dinner he wears evening dress, first removing the yarmulke that he seems to wear when he’s not doing business.

FIGURE 1 Patrick Stewart as Shylock, in his office, in the 2011 Royal Shakespeare Company production, directed by Rupert Goold. Photo by Ellie Kurttz © RSC.

But after Jessica’s elopement, we see the emotional strain reflected, albeit minimally, in Shylock’s costume for 3.1; the bow tie that Jessica had tied for him is now undone. By the trial scene, not only does he wear a dark suit, but also a yarmulke, while the fringes of the tallit katan (small tallit) are visible under his jacket. Moreover, as he prepares to attack Antonio, he puts on a larger blue-and-white striped tallit, and we can hear a murmured prayer in Hebrew (see Figure 2). The costume change emphasizes Shylock’s new perspective, and the seemingly incongruous Las Vegas setting becomes a useful background. For this Shylock at first does not really understand that being Jewish means to live, always, in a society that quietly, or overtly, hates him. He may not perceive himself as hiding, but perhaps as superior – the only grown-up in a world of games, including the games available in the casino he owns. But when that game-world intrudes, he finally realizes the hatred. The moment is quietly nasty: Salerio and Solanio are seated at a table down left; when Shylock enters, and moves to a table up right, Solanio makes a hissing sound, and a gesture of ‘turning on the gas’. The audience doesn’t know if Shylock has or hasn’t heard this not-very-subtle allusion to the Holocaust, but a few minutes later, as Shylock confronts the two men, asking, ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’ (3.1.58), he hisses ‘usss’ in a way that makes clear he did hear.

FIGURE 2 Patrick Stewart as Shylock, at the trial, in the 2011 Royal Shakespeare Company production, directed by Rupert Goold. Photo by Ellie Kurttz © RSC.

So, too, in 1993, David Calder’s Shylock looked supremely comfortable in the business world that dominated the stage; his office was on the main stage (unlike the upstage ‘office’ where Bassanio seemed to work, along with Gratiano), he wore a well-cut suit, and his assimilation into the financial world was underscored by the presence in that office of a noticeably foreign-looking Tubal. Textually, Tubal doesn’t enter the play until 3.1, when he comes to tell Shylock that attempts to find Jessica have not succeeded. However, in the 1993 RSC production, Tubal, in a long dark coat, a yarmulke and side curls, made his presence felt in 1.3, when he came over to whisper in Shylock’s ear, so that the hesitation about lending money to Bassanio could be ended, with a reference to Tubal, ‘a wealthy Hebrew of my tribe’ (1.3.53), as the source of that large sum. When we saw Calder’s Shylock on his own, he wore a luxurious smoking-jacket, listened to Brahms and gazed at a framed photograph of (we assumed) his late wife. And again, the loss of Jessica seemed to send Shylock back to his Jewish identity. When Calder’s Shylock complained to Tubal, ‘The curse never fell upon our nation till now. I never felt it till now’ (3.1.77–8), the line came with a bitter sense of realization that he could not escape from being Jewish, no matter how much money he had or what clothes he wore. Indeed, when he appeared in the courtroom, he now wore the kind of long dark coat that we had seen Tubal wearing, and his appearance was no longer that of the merchant banker but of the outsider Jew.

Both of these productions (1993 and 2011) were developments of the crucially revealing production of the second half of the twentieth century, at the National Theatre in 1970, directed by Jonathan Miller, with Laurence Olivier as Shylock. I am not alone in this judgment (Bulman 1991: 75–100; Drakakis 2011: 131–2), but let me suggest the choices that have been most influential, starting with the notion that Shylock is, in Olivier’s terms, not Fagin but Disraeli (Gilbert 2017: 291–316). ‘I was determined to maintain dignity and not stoop physically and mentally to Victorian villainy’, wrote Olivier (Olivier 1986: 119), and that choice, filtered through and refined by Jonathan Miller, was central. Portia famously asks, ‘Which is the merchant here, and which the Jew?’ (4.1.170), and Olivier’s performance and costume made that question not simply plausible but integral to seeing Shylock as an insider, not an outsider, as a wealthy banker, not a scruffy loanshark. The nineteenth-century setting was particularly useful, since ‘allowing Shylock to appear as one among many businessmen, scarcely distinguishable from them, … made sense of his claim that, apart from his customs, a Jew is like everyone else’ (Miller 1986: 155).

The line from Olivier to David Suchet’s jovial smiling Shylock wearing an expensive fur-trimmed coat (RSC, 1981) to David Calder to Patrick Stewart is clear, and was echoed in the United States by Al Pacino in 2010 (first in Central Park, then on Broadway). Pacino, like these others, was a wealthy and prosperous Shylock; though he wore a yarmulke and glasses, he sported a three-piece suit and seemed similar in class status to Antonio (Byron Jennings). But Antonio was noticeably reluctant to shake Shylock’s hand; there was an uncomfortable silence after ‘Your worship was the last man in our mouths’ (1.3.56), as Antonio looked at Shylock’s outstretched hand and finally made the briefest move he could, clearly not wanting to touch him.

In addition to establishing the possibility of playing Shylock as a would-be insider, the National Theatre’s 1970 Miller-Olivier production also raised, albeit subtly, the notion of a homosexual relationship between Antonio and Bassanio, something that the RSC had done in 1965 (dir. Clifford Williams), with Brewster Mason and Peter McEnery. Some reviewers pointed explicitly to that relationship in 1965, while others did not, just as in 1971 (dir. Terry Hands), where the subtlety of Tony Church’s performance as Antonio suggested an unrequited love for Bassanio without being obvious. For the National Theatre’s 1970 production, Miller clearly thought of Antonio and Bassanio in terms of ‘the relationship between Oscar Wilde and Bosie where a sad old queen regrets the opportunistic hetero-sexual love of a person whom he adored’ (Miller 1986: 107), and again one sees how the nineteenth-century setting both allowed and suggested this emphasis.

Later productions have made the Antonio/Bassanio relationship even more clearly one of homosexual affection, usually repressed by Antonio, though felt by Bassanio, and sometimes exploited. In 1987 (and with a Renaissance setting), John ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Preface

- Introduction: Recent Trends in Merchant of Venice Criticism M. Lindsay Kaplan

- 1 ‘Lend it rather to thine enemy’: Accentuating Difference in The Merchant of Venice

- 2 Dangerous Border Crossings: Nicolas Stemann’s Merchant in Munich

- 3 Thomas Jordan’s ‘The Forfeiture’: A Mercantilist Rewriting of Shakespeare

- 4 Jessica, Women’s Activism and Maurice Schwartz’s 1947

- 5 ‘Woolly Breeders’: Animal Generation and Economies of Knowledge in The Merchant of Venice

- 6 ‘The means whereby I live’: Deep Play in The Merchant of Venice

- 7 ‘Qualities of Breeding’: Race, Class and Conduct in The Merchant of Venice

- 8 Jessica, Sarra, Ruth: Jewish Women in Shakespeare’s Venice

- 9 ‘Marvellously Changed’: Shakespeare’s Repurposing of Fiorentino’s Doting Godfather in The Merchant of Venice

- 10 Balthazar’s Beard: Looking (Again) Into the Merchant’s Closet

- Works Cited

- Index

- Imprint