![]()

Part I

Globalizing forces and the growth of maritime knowledge in the Atlantic world, c. 1660–1730

![]()

Introduction

Globalization between c. 1660 and 1730

In 1675, Arent Roggeveen from Middelburg and the publisher Pieter Goos from Amsterdam published a new sea atlas called Het eerste deel van het Brandende Veen. This sea atlas covered the entire western part of the North Atlantic between the Amazon and the banks of Newfoundland. Besides a small-scale survey chart of the Atlantic to the north of the equator, the atlas contained twenty-nine large-scale charts of the eastern coastline of the Americas and the principal islands in the Caribbean, interspersed with sailing directions, coastal views and other pieces of useful information on particular places, such as the location of shallows, anchorages and wells.1 All the charts had been drawn by Roggeveen and the written materials bore his name, too.

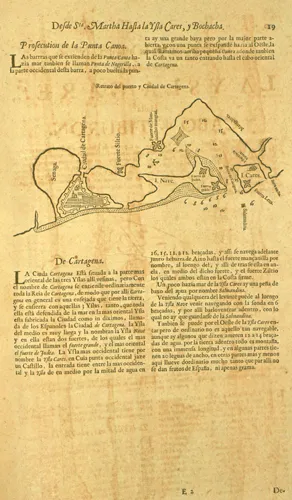

Neither Roggeveen nor Goos had ever sailed the ocean themselves. Roggeveen was a surveyor, gauger and teacher of mathematics, astronomy and navigation by trade. Between about 1670 and his death in 1679, he also held the position of examiner of pilots at the Zeeland Chamber of the VOC.2 Roggeveen claimed that he had collected the data for his atlas not by copying from existing works, but by carefully gathering information from experienced ‘shipmasters and pilots’ – an enterprise that had taken him about ten years.3 A second part of Roggeveen’s atlas, containing twenty-five charts of the coast of West Africa, was brought out by another Amsterdam publisher, Jacobus Robijn, in 1685. This part was dedicated to the Elector of Brandenburg, who together with a number of merchants from the Dutch Republic had just founded a company to trade in this very region. English, Spanish and French editions were soon published in Amsterdam, too (Figure 1).4

Figure 1 Map and description of Cartagena on the Spanish Main, from Arent Roggeveen, La primera parte de monte de turba ardiente (Amsterdam 1680). Special Collections Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Separate printed charts of the Atlantic Ocean, or parts of it, had been produced before. A Mercator chart of the northern part of the Atlantic, for example, had been published by the Amsterdam firm Blaeu in the late 1620s and had been reprinted many times. Roggeveen’s Brandende Veen (aka The Burning Fen, El Monte de turba ardiente, La Tourbe ardante), however, stands out for being the first printed atlas of the North Atlantic to have appeared in any European language. It comprised a huge amount of data, both visual and verbal, on a large part of the North Atlantic, and this state-of-the-art overview was freely available for anyone who was prepared to pay for it. The atlas thus constituted a striking leap in the circulation of maritime knowledge.

The appearance of the Brandende Veen was an outcome of the globalization that had taken place in the Atlantic orbit from the early sixteenth century onwards. As a synthesis of knowledge on spatial features of the ocean, it could serve, in turn, as an aid to globalization. After all, the Brandende Veen was a useful device to help seamen to find their way more easily and safely across the ocean, and thus to assist the growth of shipping. And the more oceanic shipping grew, the denser the connections between different parts of the Atlantic world became and the further globalization advanced.

Remarkably, this innovative sea atlas was produced on the initiative of private entrepreneurs in a country that had just been forced to abandon most of its colonial empire in the Atlantic – namely, the Dutch Republic. At this point, self-organization, linked to the rise of a new trading company (the Brandenburg African Company), was clearly beyond what imperial or religious machines were able to achieve. It is a telling example of the new ways in which globalizing forces and the growth of maritime knowledge became connected from the late seventeenth century onwards. As this chapter argues, from this time onwards, self-organization as a globalizing force became an important ingredient in the growth of maritime knowledge in the Atlantic. The Brandende Veen exemplified this momentous change.

The Brandende Veen appeared when globalization began to gather speed in the Atlantic world. Contacts, interactions and exchanges between different parts of the Atlantic orbit became more frequent, leading to greater interdependence. The Atlantic Ocean became more crowded with ships, and ships carried more and more people and goods across the ocean.

The changes in the numbers of ships, the spread of sailings throughout the year and the density of connections between different locations in the Atlantic between the 1660s and the 1730s have been extensively documented for the English Atlantic. Ian Steele has shown that ‘the number of English transatlantic and inter-colonial voyages accomplished in any one year rose dramatically in the lifetime before 1740’.5 As shipping expanded, the average passage time on transatlantic routes decreased. For example, the average length of voyages in the tobacco trade between Virginia and Britain fell from eight months in the 1680s to seven months in the 1720s. The speed and frequency of communication also improved, because more and more ships sailed outside the common, ‘‘‘optimum” shipping seasons’.6 One by-product of the expansion of transatlantic shipping was a shift in the regional spread of lighthouses in the British Isles. While the biggest concentration of lighthouses before the end of the seventeenth century could be found on the east coast between the Firth of Forth and North Foreland, more and more structures now arose on the south-west and west coasts of England and Scotland. Although some of the lighthouses were erected and maintained by the corporation of Trinity House of Deptford (London), many new structures were built and exploited by private entrepreneurs through leases from Trinity House or patents from the Crown.7

Moreover, postal services were introduced in England and the colonies overseas during the War of the Spanish Succession. Regular packet boat services began to operate between England, the West Indies and New York, which showed that sailings to schedule were a feasible option. Once shipping and trade between West Indies and North American colonies expanded, the flow of news between these p arts of the English empire increased, too. All of these changes helped to ‘shrink’ the Atlantic,8 and thus contributed to globalization.

In the French Atlantic, many more ships from France or the French colonies were arriving in Quebec or Martinique in the 1730s than twenty years before. Most of these arrivals in colonial ports were merchantmen. Merchant ships provided an indispensable means of communication for entrepreneurs and government officials alike, and were the most important carriers of letters between the different parts of the French Atlantic. The number of French slave voyages to French and Spanish possessions in America soared after the War of the Spanish Succession; in the 1720s, there were seven times more slave voyages than there had been in the 1670s.9

The density of shipping and trade within the Caribbean significantly increased from 1700 onwards. In this intra-Caribbean traffic, Curaçao and St. Eustatius, which were under the authority of the Dutch West India Company (WIC), long played a pivotal role. After receiving free port status from the WIC, both islands became important hubs in the growing traffic between the English, French, Spanish and Dutch colonies in the West Indies and the American mainland. Curaçao in particular was a key source of slaves for the Spanish Caribbean islands and the Spanish Main up until the 1730s. The expansion of the intra-Caribbean network of trade and shipping more than offset the decline in Dutch bilateral trade with the English and French colonies in the West Indies, which started in the later seventeenth century.10

Spanish Atlantic shipping, meanwhile, lagged far behind. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, fewer ships sailed from Spain to the Americas than a hundred years beforehand. Only a few dozen Spanish merchantmen and warships made the Atlantic crossing each year. Sailing patterns throughout the year remained unchanged: one fleet each to Vera Cruz and the Isthmus of Panama, one combined return fleet from Havana to Spain. Until the 1760s, no more than one mail packet a year left Spain for Cartagena. Spanish ships were almost entirely absent in the slave trade; no more than five slave voyages were carried out under the Spanish flag between 1676 and 1700, and none in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. The number of enslaved people arriving under Spanish flag in the Americas dropped from more than 220,000 between 1580 and 1640, via 21,700 between 1641 and 1700, to a mere 300 in the period between 1701 and 1760.11

Slaves for the Spanish American colonies were mostly supplied, legally or illegally, by traders from other European nations. In the seventeenth century, Portuguese traders were the major suppliers of African slaves to the mining industries in the Spanish Americas.12 The sharp decline in the slave trade under Spanish flag after 1640 was to some extent offset by the growth in imports of slaves from British, Dutch, Danish and French colonies in the Americas. After 1700, there was a massive rise in the direct slave trade from Africa to Spanish America conducted by merchants and mariners from other European nations. Under the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, the British Crown received the exclusive right to provide slaves to the Spanish dominions for thirty years. Spanish America thus became well connected with the rest of the Atlantic thanks to the growing volume and frequency of shipping between the British, Dutch and French colonies and trading posts and the Spanish American ports.13

The Atlantic also became more crowded with fishing boats and whaling ships. From the early sixteenth century, a growing number of European fishermen crossed the Atlantic every year in search of cod and other species of fish that swarmed the sea between Cape Cod, Massachusetts and the Grand Bank of Newfoundland. Year after year, myriads of fishing boats from Portugal, France, England and Spain gathered in the northwest Atlantic to bring in a rich harvest of fish for sale on European markets. The number of English vessels sailing to the Newfoundland fishing grounds rose from about 30 in the 1570s to some 250 in 1615, employing 6,000 men. French cod fishing outstripped the English fisheries by the end of the seventeenth century. The French catch was bigger than the English one, and it remained so until the Seven Years’ War. In the 1720s, cod from the banks of ‘Terreneuf’ was said to be ‘eagerly consumed in Paris and other important cities in France’.14

A new phenomenon in the later seventeenth century was that colonists from New England and Newfoundland settlers, who had initially only practised inshore fishing, also entered the cod fisheries with their own small vessels and on their own account. They subsequently started to export fish to mainland colonies further south, to English plantation colonies in the Caribbean and eventually to Madeira and ports on the Iberian Peninsula.15 New Englanders thus began to make a transition from inshore fishing and coasting to offshore fishing and ocean shipping. In this way, transatlantic networks of shipping and trade were built both from the New and the Old World.

Whales were abundant in the northwest Atlantic. Native Americans rarely, if ever, hunted for great whales, but they made use of the remains of drift whales stranded on the shores eastwards of Long Island. From the 1650s, New Englanders ventured out into coastal waters to catch whales. When stocks of whales became depleted in the early eighteenth century, they sailed to Newfoundland and the coast of the Carolinas to practise whaling in the open seas. By 1730, Nantucket was the home port for twenty-five ships employed in long-distance whaling.16 European whaling ships had entered these parts of the Atlantic before. Basque whalers hunted for whales in the straits between Labrador and Newfoundland between c. 1530 and the early seventeenth century, and then moved the centre of their activities to the ocean area to the west of Spitsbergen. Ships from England, Denmark, France, the Dutch Republic and Northern Germany joined the hunt after c. 1610. When catches in the seas near Spitsbergen showed a sharp decline after 1700, Dutch and German whalers started to look for new fishing areas further to the west. In 1719, twenty-nine ships from the Dutch Republic and four from Northern German ports entered the Davis Strait, between Greenland and Baffin Island, to hunt for whales. Disco Bay on the west coast of Greenland yielded particularly rich harvests. The Inuit used to catch whales near these shores, too, as journals and travel accounts of European whalers attest. In the decades that followed, the annual number of Dutch and German whalers sailing to the Davis Straits ran into the dozens. As a sideline of whaling, some barter trade with the Inuit develope d as well.17 Thus, the expansion of whaling led to a multiplication of contacts across the Atlantic.

Growing shipping and trade in the Atlantic also involved a vast increase in the transport of people. Sailing ships carried huge numbers of people across the ocean. More than 104,000 Africans were transported as slaves on ships under European flags between 1671 and 1680, slightly more than 10,000 per year. In the 1720s, the number of enslaved people transported per year had risen to 47,000. Most of the slaves in this period were brought to the Caribbean and Brazil; the others were mainly carried to the Spanish Main and to mainland North America.18

The numbers of voluntary and involuntary migrants who crossed the Atlantic from Europe in this period – as colonists, merchants, soldiers, indentured servants or convicts – are only very approximately known. For the Spanish Atlantic, historians conjecture that migration movement slowed down after about 1650. Whereas some 450,000 emigrants left Spain for America before 1650...