- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

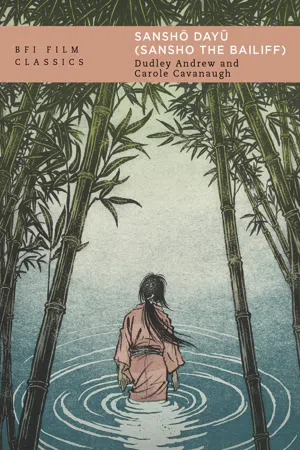

Sansho Dayu (Sansho the Bailiff)

About this book

Kenji Mizoguchi's masterpiece Sanshô Dayû (1954) retells a classic Japanese folktale about an eleventh-century feudal official forced into exile by his political enemies. In his absence, his children fall under the corrupting influence of the malevolent bailiff Sansho. In their study of the film, film scholar Dudley Andrew and Japanese literature professor Carole Cavanaugh highlight the cultural, aesthetic and social contexts of this film which is at once rooted in folk legend and a modern artwork released in the aftermath of World War II. This edition includes a new foreword by the authors in which they consider the film's contemporary parallels in modern slavery and children torn from their families by malevolent authorities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sansho Dayu (Sansho the Bailiff) by Dudley Andrew,Carole Cavanaugh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Mizo Dayū

Dudley Andrew

‘Mizoguchi the Master’ was the title of the centennial retrospective organised in 1998 by the Japan Foundation.1 ‘Master’ signifies someone at the summit of an art or craft; it also carries the less agreeable connotation of paternalism, as in ‘slave-master’. ‘Mizo Dayū’ is equally ambivalent. Mizoguchi is the ‘Bailiff’, serving tradition as its implacable cinematic overseer. But ‘Dayū’ also means ‘professional story-teller’, one through whom legends are revivified.2 This is the role Carole Cavanaugh highlighted, seeing the legend of ‘Sanshō’, with its scarcely locatable origin, pass through Mizoguchi’s telling on its way to an indefinite future. Such is the nature of any fertile legend, I too begin by saying. But I end quite differently, on the closing down of the legend in the finale of Mizoguchi’s version, a version which, though perhaps not definitive, appears – in all senses of the term – conclusive.

Where the longevity and deployment of the ‘Sanshō’ tale inside Japan are unmistakable, so too has been that tale’s increasing internationalization via Mizoguchi retrospectives around the globe. In1994 Criterion issued a variorum laser disc of Sanshō Dayū, making use of the scholarly research on the legend commissioned by the American filmmaker Terrence Malick. Few were aware of Malick’s short-lived adaptation of the film for the New York stage in 1994 until a still from the Mizoguchi movie appeared in the Sunday New York Times feature on The Thin Red Line. 3 Malick even thought to remake Sanshō Dayū.

A 1993 rehearsal of the Terrence Malick stage version at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (courtesy Geisler/Roberdeau Productions)

This dynamic afterlife substantiates the two related themes that run through Mizoguchi’s version: the theme of ritual narration which makes possible the theme of survival. As for the film’s survival, the critics at Cahiers du Cinéma had much to do with that. They ranked Sansho Dayu as the top film of 1960, the year of its Paris release, ahead of L’avventura, A bout de souffle (Breathless) and Tirez sur le pianiste (Shoot the Piano Player) in that order. They applauded the purity of its construction, the mature wisdom of its narration. And yet they sensed something fresh about Mizoguchi’s story-telling, a ‘tableau primitif’,4 wherein you could sense the rebirth of cinema. A tale of origins, Sansho Dayu is set at so remote a time that Mizoguchi could imagine himself returning to the rudiments of both morality and narrative art at one and the same stroke. The urge to renew himself and his art through ‘Sanshō’ welled up in Terrence Malick as it did in Mizoguchi, a paradoxical urge given the familiarity of the story. This chapter likewise aims to return to a basic conception of the cinema by refreshing what is familiar in Mizoguchi’s masterful film, following his own route to the origin of what is valuable only in repetition.

Mysterious traces harbouring ancient legends

The Legend and the Legendary

Recall the opening shot: the ruined stumps of columns of an ancient manor, over them appears a scripted title whose literal translation should read:

The origin of this legend of ‘Sansho the Bailiff’ goes back to the Heian period when mankind had not yet opened their eyes to other men as human beings. It has been retold by the people for centuries and is treasured today as one of the epic folk tales of our history.5

In determining to return to these dark ages and to perpetuate this legend Mizoguchi surely had his own moment in mind, the humiliating decade 1944-54. An account of that decade by Shunsuke Tsurumi contains a telling anecdote:

During the last stage of the war, a novelist recruited for compulsory labor service commented that his way of carrying earth in a crude straw basket seemed like a return to the age of the gods as told in the legend. Our manner of living at the outset of the occupation had much in common with the ancients.6

The legend referred to might as well be Mizoguchi’s Sanshō Dayū, where characters do haul wood on their backs and where we are told the foundations of civilization are not yet in place.

Yet the nobility of Sanshō Dayū’s images and music exudes a certain longing for this cruel, chaotic era, perhaps because it was foundational. We know that as soon after the war as the American censors permitted – indeed even before they permitted – Mizoguchi immersed himself and his audiences in earlier periods, skirting their interdictions against period films in his biography of the eighteenth-century artist Utamaro (1946). With the occupiers gone but with modernity rising from the rubble like a soaring skyscraper, this time he travelled further back in history than he had ever gone. Tsurumi claims that at the onset of the Occupation in 1945, Japanese art was at the ‘cave painting’ stage. Mizoguchi must have felt closer to the bold designs of such elemental expression than to the everyday realism that was beginning to pour from television sets, introduced commercially in Japan in 1954. He recounts Sanshō Dayū in an ancient manner. His characters (the tyrant, the dutiful daughter, the greedy official, the kidnappers) derive from a folkloric style that dispenses with the fussy psychologism of modern fiction. Mizoguchi delivers a bold ‘cave painting’ suitable to the primitive situation to which the war and Occupation had reduced this culture. His film aims to be as fundamental as a legend.

Legends store primitive power that can be called up as required but that no adaptation exhausts. Gilles Deleuze writes of beleaguered peoples inventing themselves by ‘making up legends’. If one takes Japan as a nation that during the Occupation became invisible to itself – when the United States prevented the past from being seen and revoked customs and traditions – then Sanshō Dayū could be said to call this people to consciousness. After three years of a Korean conflict in which Japan was used as a staging area, many Japanese must have felt inducted into an international drama scripted by the United States. Legends rally suppressed, ‘pre-existent peoples’. Deleuze writes: ‘To catch people in the act of making up legends is to apprehend the movement of a people’s constitution.’7 Was Mizoguchi among the anti-modernists who considered themselves an insurgent minority of this sort and who wanted to recover the majority discourse of a healthy nationalism that had been hijacked by the military in 1931 and then suppressed by the Americans in 1945? Sanshō Dayū represents Japan as created by a ‘pre-existent people’ and challenges modern Japanese to resemble their ancient ancestors.

In this Mizoguchi can be said to follow the lead of the celebrated anthropologist Yanagita Kunio who, early in the century, recorded tales of the mountainous regions where he believed uncorrupted Japanese origins lay dormant. Questioning modernization, prescribing a prophylaxis against its encroachments, Yanagita mined the lore of the Tōno district in northeastern Honshū, publishing a famous anthology of legends in 1910. Five years later, he took up the Sanshō tale, just after Mori Ōgai had brought out his sensationally popular version.8 To Yanagita, ‘Sanshō’ is the kind of tale that springs from mountain sources (it opens in his beloved Tōno area) and should flow down to the corrupted central cities. Not that he fought modern technology. Indeed Yanagita took heart in the rail system that had united the country and that could bring rural values in from the periphery to Tokyo Station which, he was famous for noting, stood facing the Emperor’s palace. The Emperor and the distant people needed to be in direct communication. Yanagita believed folk-tales had always served as the substance and the means of this communication, ‘Sanshō’ being a prime example. Yanagita and Mizoguchi employ Western technology (anthropology and cinema respectively) to broadcast back to the capital a story whose endearing character comes from its homely origins in the far edges of the world.

Always pious before the past, Mizoguchi made at least a pretence of historical research, given the production schedule.9 Details of gesture, garments, architecture, traits of geography and class are evident in the hats, boats, temple doors, artisanal objects and landscape. Such fussy effort could amount to an effete, academic antiquarianism if the ‘difference’ displayed in the distinctive texture of this Japanese past did not contribute to ‘Transfiguring Japan’. This is the title of a chapter in Marilyn Ivy’s Discourses of the Vanishing, devoted to the post-war revival of travel narratives like Sanshō Dayū. While a conscious effort to ‘discover’ and ‘exoticise’ the land flourished during the 70s and 80s as Nihonjinron (pious study of Japan), this impulse had sprung up as soon as the American controls were removed and had roots in the Japanese ‘exceptionalism’ of the 30s.10 With nationalism in mind, this family odyssey film plots a map of the archipelago. From Mutsu province in the far northeast, the father is exiled to the southern island of Tsukushi. Meanwhile the rest of the family is intercepted in their trip along the coast of the Sea of Japan, the children enslaved in the Tango prefecture (remote enough from Kyoto to be ruled by a functionary of a corrupt minister), while their mother is marooned on Sado, an island that may stand for the most outlying members of the national body. While the story renders the nation spatially, a temporal axis is staked out in the prologue where the film is explicitly taken to be the most recent of versions that have been passed down through the centuries, thereby compressing Japanese history in the process. One of the first post-Occupation films to figure Japan geographically and historically, Sanshō Dayū must be considered a national epic or anthem.

This anthem is doleful, keyed by the cry of Tamaki from the top of the cliff overlooking the sea. ‘Zushiō-oo, Anju-uu,’ she calls, a mother bird, tethered and bereft of her fledglings. The camera observes her from a high angle, as, leaning on a stick, she hobbles along the bluff following the direction of her cry. We sense her entire body strain to cross the sea with the sounds she sings; we sense it because an offshore wind blows her unbound hair across her cheeks and toward her children. Anju feels her mother’s presence come to her through the guarded gates of the compound. The maternal call, emanating from a most distant and rugged corner, reaches and silently sustains her.

Tamaki’s cry blows across Japan

Surely Mizoguchi meant his film to blow across the nation, carrying a mother’s cry so as to reawaken in those who hearken to it a memory of belonging to a ‘family’ that exile (or war) has cruelly dispersed. The cumbersome mechanism of the cinematic apparatus is given over to recovering this pure plaintive cry. It records, amplifies and broadcasts the nearly inaudible echo of a legend that scholars believe had historical origins in the declining years of the Heian period when absentee landlords, virtually independent of government, ruled domains and workhouses overseen by their bailiffs. The earliest extant mention of this tale of slavery and liberation dates from the fourteenth century in the form of a Buddhist homily (soon comprising both a canonical version and a popular ‘travelling’ tale recited by mendicant priests).11 During the Tokugawa period Sanshō, Anju and Zushiō were featured in plays produced on both the kabuki and bunraku stages, especially the latter. Then in 1915, Mori Ōgai, among the most famous writers in the land, reworked the sekkyō-bushi (Buddhist homily), effectively stabilizing it with his rigorous prose, and warping it with his Confucian sentiments. Known for his clarity and naturalism, in this story Ōgai ventured toward a spiritual zone beyond the social where ‘the slight aura of mystery surrounding the story permitted him to expand his imagination to an unusual level of sustained lyric sensibility’.12

Mizoguchi would be drawn into this zone and would wherever possible inflate Ōgai’s spiritual atmosphere, wringing from it a far more tragic tone. Take Anju’s suicide. Ōgai narrates it with characteristic obliquity: ‘a party of pursuers dispatched by Sansho the Bailiff in search of Anju and Zushiō … found a pair of small straw shoes on the shore of the lake below the slope. The shoes were Anju’s and she could not be found.’ Mizoguchi, at once more direct and more suggestive, watches Anju wade slowly but resolutely into the lake; then, after a cutaway to a faithful friend praying before this pathetic scene, he comes back with a closer shot of the lake, now empty and still, b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title

- Contents

- Foreword to the 2020 Edition

- Synopsis

- Sanshō Dayū and the Overthrow of History

- Mizo Dayū

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- Copyright