eBook - ePub

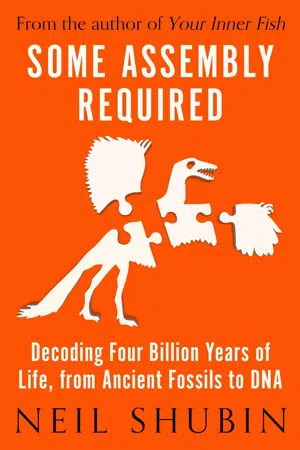

Some Assembly Required

Decoding Four Billion Years of Life, from Ancient Fossils to DNA

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

‘Intimate and thoughtful… Exciting… [A] sweeping evolutionary history.’ Science

The author of the bestselling Your Inner Fish gives us a brilliant, up-to-date account of the great transformations in the history of life on Earth.

This is a story full of surprises. If you think that feathers arose to help animals fly, or lungs to help them walk on land, you’d be in good company. You’d also be entirely wrong.

Neil Shubin delves deep into the mystery of life, the ongoing revolutions in our understanding of how we got here, and brings us closer to answering one of the great questions – was life on earth inevitable…or was it all an accident?

The author of the bestselling Your Inner Fish gives us a brilliant, up-to-date account of the great transformations in the history of life on Earth.

This is a story full of surprises. If you think that feathers arose to help animals fly, or lungs to help them walk on land, you’d be in good company. You’d also be entirely wrong.

Neil Shubin delves deep into the mystery of life, the ongoing revolutions in our understanding of how we got here, and brings us closer to answering one of the great questions – was life on earth inevitable…or was it all an accident?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Some Assembly Required by Neil Shubin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Five Words

SOME PEOPLE FIND THE SUBJECT of their life’s work in a laboratory or in the field. I found mine in a single projected slide.

Early in my graduate student days, I took a class taught by a senior scientist on the greatest hits in the history of life. It was a whirlwind course, a form of speed dating with big puzzles in evolution. Fodder for each week’s discussion was a different evolutionary transformation. In one of the initial sessions, the professor displayed a simple cartoon that showed what we knew back then, in 1986, about the transition from fish to land-living animals. At the top of the sketch was a fish and at the bottom was an early fossil amphibian. An arrow pointed from the fish to the amphibian. It was the arrow, not the fish, that caught my eye. I looked at that figure and scratched my head. Fish walking on land: How could that ever happen? This seemed like a first-class scientific puzzle on which to hang my shingle. It was love at first sight. Thus began four decades of expeditions to both poles, and several continents, in the hunt for fossils to show how this event transpired.

Yet when I tried to explain my quest to relatives and friends, I was often met with pained glances and polite questions. Transforming a fish into a land-living animal meant developing a new kind of skeleton, one with limbs for walking rather than fins for swimming. Moreover, a new way of breathing, using lungs rather than gills, had to arise. So, too, feeding and reproducing had to change—eating and laying eggs in water is entirely different from what happens on land. Virtually every system in the body would have to transform simultaneously. What good would it be to have limbs for walking on land if the animal couldn’t breathe, feed, or reproduce? Living on land requires not just a single invention but the interplay of hundreds of them. The same difficulty holds for each of the thousands of other transitions in the history of life, from the origins of flight and bipedal walking to the origins of bodies and life itself. My quest seemed doomed from the start.

The solution to this dilemma is embedded in a famous quote from the playwright Lillian Hellman. In describing her life—from being blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee during the 1950s to her hard-living ways—she once said, “Nothing, of course, begins at the time you think it did.” With that phrase, she unintentionally described one of the most powerful concepts in life’s history, one that explains the origin of most every organ, tissue, and bit of DNA in all creatures on Planet Earth.

The seeds for this idea in biology began as a consequence of the work of one of the most self-destructive figures in all of science, who, true to form, changed the field by being wrong.

To grasp the meaning of recent discoveries in the genome, we need to turn to an earlier age of exploration. Victorian Britain was a crucible for enduring ideas and discoveries. There is something poetic to the notion that knowing how DNA works in the history of life relies on ideas developed during an age when people didn’t know that genes even existed.

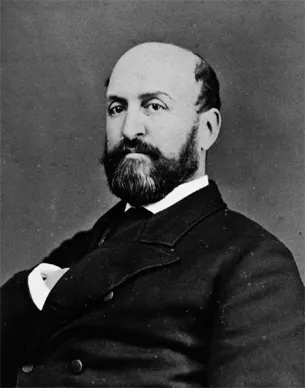

St. George Jackson Mivart (1827–1900) was born to zealously evangelical parents in London. His father had risen from being a butler to owning one of the city’s major hotels. Mivart Senior’s position gave his son the chance to achieve the social standing of a gentleman and accorded him the privilege of entrée into the career of his choice. Like his contemporary Charles Darwin, Mivart was born with a passion for nature. As a child, he collected insects, plants, and minerals, often making copious field notes and devising classification schemes. Mivart seemed destined for a career in natural history.

Then the dominant theme of his personal life—struggle with authority—intervened. In his preteens, Mivart became increasingly uncomfortable with his family’s Anglican faith. To the great consternation of his parents, he converted to Roman Catholicism. This move, bold for a sixteen-year-old, had unforeseen consequences. Mivart’s newfound allegiance to the Catholic Church meant that he couldn’t attend Oxford or Cambridge, because entrance to English universities was closed to Catholics at that time. Unable to matriculate to any program in natural history, he took the only remaining option—studying law at the Inns of Court, where one’s choice of religion was not an obstacle. Mivart became a lawyer.

It is not clear if Mivart ever practiced law, but natural history remained his passion. Using his status as a gentleman, he entered scientific high society, where he developed relationships with key figures of the day, most notably Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–95), who was soon to become a prominent defender of Darwin’s ideas in the public sphere. Huxley was an accomplished comparative anatomist in his own right and had assembled a cadre of keen apprentices. Mivart became close to the great man, working in his lab, even taking part in Huxley family gatherings. Under Huxley’s tutelage, Mivart produced seminal, albeit mostly descriptive, works in primate comparative anatomy. These detailed accounts of the skeleton remain useful today. By the time Darwin published his first edition of On the Origin of Species in 1859, Mivart considered himself a supporter of Darwin’s new idea, likely a by-product of being enveloped by Huxley’s fervor.

But, as had happened with the Anglican faith of his youth, Mivart developed strong doubts about Darwin’s ideas and intellectual objections to the Darwinian idea of gradual change. He began to voice his notions in public, first meekly, then with greater force. Marshaling evidence in support of his dissenting view, he composed a response to On the Origin of Species. If he had any remaining friends among his old pals in the natural history world, he lost them with his single-word variant of Darwin’s title: On the Genesis of Species.

St. George Jackson Mivart, who managed to offend every side in the evolution debate

Mivart then started giving the Catholic Church a hard time too. He wrote in church periodicals that virgin birth and the infallibility of church doctrine were as implausible as Darwin’s ideas. With the publication of On the Genesis of Species, Mivart was virtually excommunicated from science. His writings led the Catholic Church to formally excommunicate him six weeks before his death in 1900.

Mivart’s challenge to Darwin offers a window into the intellectual knife fights of Victorian Britain and articulates a stumbling block that many people continue to have with Darwin. Mivart opened his attack by referring to himself in the third person, using language intended to establish his credibility as open-minded: “He was not originally disposed to reject Darwin’s fascinating theory.”

Mivart begins making his case with a substantial chapter outlining what he saw as Darwin’s fatal flaw, calling it “the incompetency of natural selection to account for the incipient stages of useful structures.” The title is a mouthful, but it encapsulates a crucial issue: Darwin envisioned evolution as consisting of innumerable intermediate stages from one species to another. For evolution to work, each of these intermediate stages had to be adaptive and increase an individual’s ability to thrive. To Mivart, intermediate stages often didn’t appear plausible. Take the origin of flight, for example. What possible use could an early stage in the origin of wings have? The late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould called this issue the “2% of a wing problem”: a tiny incipient wing in a bird ancestor would appear to have no utility at all. At some point it might be big enough to help an animal glide, but a tiny wing couldn’t be used for any type of powered flight.

Mivart offered one case after another in which intermediate stages seemed implausible. Flatfish have two eyes on one side of the body, giraffes have long necks, some whales have baleen, various insects mimic tree bark, and on and on. What use could tiny fractional displacements of the eyes, elongations of necks, or subtle variations in coloration have? How about a jaw with only a sliver of baleen to feed an entire whale? Evolution, it would appear, consisted of innumerable dead ends between the endpoints of any major transition.

Mivart was one of the first scientists to call attention to the observation that major transitions in evolution do not involve a single organ changing; rather, whole suites of features across the body have to change in concert. What was the use of evolving limbs to walk on land if a creature didn’t have lungs to breathe air? Or, as another example, consider the origin of bird flight. Powered flight requires many different inventions—wings, feathers, hollow bones, high metabolisms. It would be useless for a creature with bones as clunky as an elephant’s or a metabolism as slow as a salamander’s to evolve wings. If entire bodies have to change for any great transformation, and many features need to change simultaneously, then how could major transitions happen gradually?

In the century and a half since the publication of Mivart’s ideas, they have been a touchstone for many critiques of evolution. At the time, however, they also served as a catalyst for one of Darwin’s great ideas.

Darwin saw in Mivart a truly important critic. He published the first edition of On the Origin of Species in 1859; Mivart’s tome appeared in 1871. For the sixth, definitive edition of On the Origin of Species, published in 1872, Darwin added a new chapter to respond to his critics, Mivart chief among them.

True to the conventions of Victorian debate, Darwin opened by saying, “A distinguished zoologist, Mr. St. George Mivart, has recently collected all the objections which have ever been advanced by myself and others against the theory of natural selection, as propounded by Mr. Wallace and myself, and has illustrated them with admirable art and force.” He continued: “When thus marshaled, they make a formidable array.”

Then he silenced Mivart’s critique with a single phrase, followed by copious examples of his own. “All Mr. Mivart’s objections will be, or have been, considered in the present volume. The one new point which appears to have struck many readers is, ‘That natural selection is incompetent to account for the incipient stages of useful structures.’ This subject is intimately connected with that of the gradation of the characters, often accompanied by a change of function.”

It is hard to overestimate how deeply important those last five words have been to science. They contain the seeds for a new way of seeing major transitions in the history of life.

How is this possible? As usual, fish provide insights.

Breath of Fresh Air

When Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt in 1798, he brought more than ships, soldiers, and weapons with his army. Seeing himself as a scientist, he wanted to transform Egypt by helping it control the Nile, improve its standard of living, and understand its cultural and natural history. His team included some of France’s leading engineers and scientists. Among them was Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772–1844).

Saint-Hilaire, at twenty-six, was a scientific prodigy. Already chair of zoology at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, he was destined to become one of the greatest anatomists of all time. Even in his twenties, he distinguished himself with his anatomical descriptions of mammals and fish. In Napoleon’s retinue he had the exhilarating task of dissecting, analyzing, and naming many of the species Napoleon’s teams were finding in the wadis, oases, and rivers of Egypt. One of them was a fish that the head of the Paris museum later said justified Napoleon’s entire Egyptian excursion. Of course, Jean-François Champollion, who deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics using the Rosetta Stone, likely took exception to that description.

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, scientific prodigy

With its scales, fins, and tail, the creature looked like a standard fish on the outside. Anatomical descriptions in Saint-Hilaire’s day entailed intricate dissections, frequently with a team of artists on hand to capture every important detail in beautiful, often colored lithographs. The top of the skull had two holes in the rear, close to the shoulder. That was strange enough, but the real surprise was in the esophagus. Normally, tracing the esophagus in a fish dissection is a pretty unremarkable affair, as it is a simple tube that leads from the mouth to the stomach. But this one was different. It had an air sac on either side.

This kind of sac was known to science at the time. Swim bladders had been described in a number of different fish; even Goethe, the German poet and philosopher, once remarked on them. Present in both oceanic and freshwater species, these sacs fill with air and then deflate, offering neutral buoyancy as a fish navigates different depths of water. Like a submarine that expels air following the call to “dive, dive, dive,” the swim bladder’s air concentration changes, helping the animal move about at varying depths and water pressures.

More dissection revealed the real surprise: these air sacs were connected to the esophagus via a small duct. That little duct, a tiny connection from the air sac to the esophagus, had a large impact on Saint-Hilaire’s thinking.

Watching these fish in the wild only confirmed what Saint-Hilaire inferred from their anatomy. They gulped air, pulling it in through the holes in the back of their heads. They even exhibited a form of synchronized air sucking, with large cohorts of them snorting in unison. Groups of these snuffling fish, known as bichirs, would often make other sounds, such as thumps or moans, with the swallowed air, presumably to find mates.

The fish did something else unexpected. They breathed air. The sacs were filled with blood vessels, showing that the fish were using this system to get oxygen into their bloodstreams. And, more important, they breathed through the holes at the top of their heads, filling the sacs with air while their bodies remained in the water.

Here was a fish that had both gills and an organ that allowed it to breathe air. Needless to say, this fish became a cause célèbre.

A few decades after the Egyptian discovery, an Austrian team was sent on an expedition to explore the Amazon in celebration of the marriage of an Austrian princess. The team collected insects, frogs, and plants: new species to name in honor of the royal family. Among the discoveries was a new fish that, like any fish, had both gills and fins. But inside it also had unmistakable vascular plumbing: not a simple air sac, but an organ loaded with the lobes, blood supply, and tissues characteristic of true human-like lungs. Here was a creature that bridged two great forms of life: fish and amphibians. To capture the confusion, the explorers gave it the name Lepidosiren paradoxa—Latin for “paradoxically scaled salamander.”

Call them what you will—fish, amphibian, or something in between—these creatures had fins and gills to live in water but a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- 1. Five Words

- 2. Embryonic Ideas

- 3. Maestro in the Genome

- 4. Beautiful Monsters

- 5. Copycats

- 6. Our Inner Battlefield

- 7. Loaded Dice

- 8. Mergers and Acquisitions

- Epilogue

- Further Reading and Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Illustration Credits

- Index