eBook - ePub

Conducting Case Study Research for Business and Management Students

- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Conducting Case Study Research for Business and Management Students

About this book

In Case Study Research, Bill Lee and Mark Saunders describe the properties of case study designs in organizational research, exploring the uses, advantages and limitations of case research. They also demonstrate the flexibility that case designs offer, and challenges the myths surrounding this approach.

Ideal for Business and Management students reading for a Master's degree, each book in the series may also serve as reference books for doctoral students and faculty members interested in the method.

Part of SAGE's Mastering Business Research Methods Series, conceived and edited by Bill Lee, Mark N. K. Saunders and Vadake K. Narayanan and designed to support students by providing in-depth and practical guidance on using a chosen method of data collection or analysis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conducting Case Study Research for Business and Management Students by Bill Lee,Mark N. K. Saunders in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & R&D. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction to Case Studies

Introduction

The purpose of this book is to provide a guide to students who decide to incorporate one or more case studies into the data collection processes that they conduct in preparation of a Masters-level dissertation. We will elaborate on what case studies are below, but a provisional definition is that a case study entails a decision to study an instance, institution or phenomenon primarily as interesting per se, rather than as a representative of a broader population. This initial decision will subsequently involve the researcher in fieldwork, collecting evidence about the phenomenon from a range of sources to seek to develop a multidimensional understanding of the case.

Masters-level students are our primary audience but this book may also provide a primer for students studying for research degrees such as PhDs or for others who are considering using case studies for the first time. In offering some form of guide, we outline two broad approaches to help structure the discussion. In defining them as broad approaches, we are intending that the reader recognizes that we are presenting each as a genre that may embrace a number of different variants, rather than a definite prescription of a single best way of conducting each type of case study. One broad approach may be considered as orthodox and starts with the reading of literature and progresses in a linear way through the development of a research question or questions, design of research, collection of data, analysis of data and writing up of the research. The other recognizes greater iteration and will be referred to throughout as an emergent approach. As will become clear below, we do not intend the term emergent to imply that it is an approach that is only just being developed; instead we use the term to infer that the case will be developed as the research proceeds when the researcher encounters new circumstances and ideas, often in unanticipated ways. So the emergent approach will not necessarily start from the reading of the literature, but may instead start with a problem or an observation or some data in the form of anecdotal evidence that the researcher finds interesting and then progresses from there to include the stages that appear in the orthodox approach, although often not in the same order as takes place in the orthodox approach.

The two approaches are not necessarily dichotomous. Indeed, some readers who are experienced in the conduct of case studies and conversant with a broad range of literature on case studies and research methods more generally may suggest that this book simplifies what some writers on orthodox case studies advocate, or it combines elements of a range of different approaches into emergent cases, or it does not centralize alternative ways of dividing case studies such as by the epistemological preferences of the researcher as is used by some other writers (e.g., Boblin et al., 2013). We recognize some legitimacy in such criticisms.

We do, however, have two main reasons for organizing the book according to the chronological order in which stages in the research process are carried out. The first main reason is that the two approaches reflect two broad traditions that are presented below when we discuss the history of case studies. The first approach is based on the principles of experimental psychology where research questions are defined within tightly defined boundaries and there are then attempts to control the boundaries and collect evidence within those boundaries so that the original research questions and findings addressed to those questions are seen to have validity. The second approach is that of ethnographic research stemming originally from anthropological studies where boundaries are not known, and where issues of interest deemed most worthy of expression in written-up findings only emerge as the research progresses. The former lends itself to a linear progression through the stages of research. The latter can accommodate a much less rigid advance through the different stages in the research process. As you may be undertaking your first research project, you may have had limited opportunities to familiarize yourself with different traditions, so this book provides you with these alternatives.

The second main reason to justify our organization of the book according to differences in the chronological order in the stages that the case study is conducted, is that the two approaches tend to reflect what happens in practice when experienced academics undertake case studies. Cases do start at different stages, not least because people may have made a number of observations, or had a number of experiences over time and they may have started to formulate ideas of why those events had occurred. In effect, they had started to define a problem before they had conducted an extensive review of the literature. Alternatively, a problem may be suggested to a researcher by someone who then provides access to evidence (see, for example, Buchanan, 2012). Only some case studies will start because people identify a gap in the literature and progress from there to conduct of the case. If the research of experienced academics progresses in different ways, it would be inappropriate to suggest that people with less experience should not also have a choice of alternatives, especially when many Masters-level students are mature and have numerous experiences that might help in defining a research problem. This book is written in a way where it will not only provide a guide to using case studies in research that has different starting points but the information provided will also help you to document a systematic explanation of what you have done and why you did it. It is worth noting at this stage that some other authors also write about ‘teaching cases’ that document a scenario and ask students to consider issues surrounding the scenario from different vantage points. We deliberately avoid consideration of teaching cases as the purpose of this book is to provide guidance around using case studies in research.

The objectives of the remainder of this chapter are threefold. The first is to expand on ideas of what constitutes case studies and the two alternative approaches. These are described here as either orthodox that involves the advanced definition of the protocol of the specific case study as a comprehensive research strategy, or emergent where the case study is perceived as a strategic choice that presupposes only using one or more institutions or instances as cases, but the exact way in which knowledge about those cases will be derived and used to add to our understanding is not pre-defined and will be finalized as a research strategy as the research progresses. The second objective is to discuss the origins of case studies partly as a means to providing an understanding of why they have been developed as ways of conducting research and to help illuminate the differences in the two approaches that are outlined. The final objective of this chapter is to outline the remainder of the book.

What is a case study?

One of the things that may surprise – and confuse – a reader new to research when reviewing the literature on case studies is the different terms that are used to explain what case studies are. For example, Janckowicz (2005: 220) has described case studies as a research method which may be defined as ‘a systematic and orderly approach taken to the collection and analysis of data’. For Janckowicz (2005: 221) case studies will then embrace different techniques – which are identical to what others have described as ‘methods’– that comprise ‘particular step-by-step procedures which you can follow in order to gather data and analyse them for the information they contain’. Robert Yin (2014), who is probably the best-known author on case studies, sometimes uses the term ‘method’ to describe a case study and at other times suggests that a case study is a research strategy which will contain a number of methods. This definition of case studies as a research strategy embracing a number of methods is one echoed by a number of other writers (see, for example, Hartley, 2004).

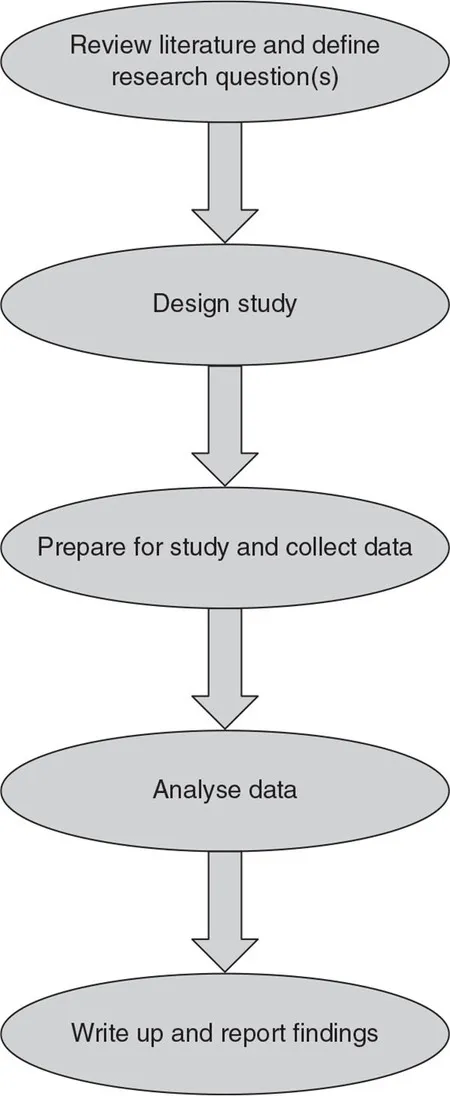

The above definitions are all aligned with orthodox approaches that tend to suggest that all research components that lead to a research output known as a case study may be collapsed into a set of decisions in advance of the study taking place. For this reason, this book will view such approaches as seeing case studies as a research strategy. That strategy will progress through a route that is primarily linear as presented in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Orthodox linear approach

It starts with a thorough literature review that will result in the formulation of clear theoretical propositions often expressed as research questions. The research then progresses to a plan for the conduct of the research which will entail theorizing about the cases in ways that will allow the generation of answers to the research questions, the evidence that will be necessary and the people whose position will enable provision of that evidence and then to the execution of that plan. Although some authors may acknowledge that some stages may be repeated, we have focussed on the aspects of linearity when providing an outline of the orthodox approach in Figure 1.1 to help distinguish the difference between orthodox and emergent approaches. The advanced definition of what is to be done in the course of such an orthodox case study is usually expressed in the form of a research protocol – see Chapter 4 for more on this. Unplanned divergence from that protocol is a violation of the research and is likely to create bias. The orthodox approach relies heavily on propositional knowledge – i.e., that which has been expressed in formulated and shared statements – derived from the literature review and determines the scope of the research. The advantage of this approach is that if the research has been designed properly to make a contribution to the literature – and perhaps to resolve a problem within a case study organization – and the case can be executed as initially conceived, early stages of the research process may be written up as the case is progressing (see Yin, 2014: 195) and the dissertation project should be completed and written up in a timely way with the desired outcome. This type of approach clearly has its supporters (e.g., Crowe et al., 2011; Yin, 2014) and it may be one which you seek to – and your dissertation supervisor encourages you to – utilize. In subsequent chapters, this book will outline how to conduct orthodox case studies.

There are, however, drawbacks with orthodox case studies. Firstly, propositional knowledge may not have captured experiential, empathetic and tacit knowledge, which can enhance understanding. To focus only on propositional knowledge is to risk excluding these other forms of knowledge from the case study. Everyone exists in a range of different communities and will be affected by a wide range of different issues. It seems less than sensible to suggest that they should not seek to think analytically about – and document – what they know about those communities and issues simply because they have not yet conducted an extensive literature view. Secondly, a reluctance to wait until a literature review has been conducted could lead to the forfeit of opportunities that provide ‘accidental access’ to an organization that constitutes an interesting site to study a particular problem (Otley and Berry, 1994: 51). Conversely, the ideal site to examine a particular research question that follows from a literature review may not be identifiable or accessible. Thirdly, once the case is started, there is a danger that the specified case study protocol could become a straightjacket that precludes new opportunities to gather evidence as they arise, or the case could lead to many false starts as new projects have to be started if new, important insights become available. Encouragement to miss such opportunities is perhaps most evident in Yin’s (2014: 55) discussion of holistic cases when he says:

The initial study questions may have reflected one orientation, but as the case study proceeds, a different orientation may emerge, and the evidence begins to address different research questions. … you need to avoid such unsuspected slippage; if the relevant research questions really do change, you should simply start over again, with a new research design.

The alternative approach to case studies being proposed here recognizes both the other forms of knowledge that enhance understanding that may need to be embodied in a case study at some point and that qualitative research that involves naturalistic settings tends ‘to be much more fluid and flexible than quantitative research in that it emphasizes discovering novel or unanticipated findings and the possibility of altering research plans in research to such serendipitous occurrences’ (Patton, 2015: 240). Not surprisingly, Stake (1995: 28) has said:

Researchers differ on how much they want to have their research questions identified in advance. Case study fieldwork regularly takes the research in unexpected directions, so too much commitment in advance is problematic.

In suggesting an alternative of emergent case studies, the objective is to realize the benefits of alternative forms of knowledge identified above and to exercise the degree of flexibility to respond to events that were not anticipated, but which might enhance the understanding that can be derived from a case. For these reasons, the suggestion here is that an emergent approach will simply view a case study as a strategic choice. The nature of the choice that is made is that empirical study of one or more institutions or instances of a phenomenon is the best way of answering a particular research question. How the choice of cases is made, decisions on the defining aspects of the cases, the theorization of any relationship between the case and a wider population, the interesting aspects of the case requiring focus and the ways to derive data to address the interesting aspects of the case are all other decisions that will be made in the course of the research. As such the strategic choice of using one or more cases may be built into a range of different research strategies that will involve conducting case studies and employing them in a dissertation, but which will emerge as the research progresses.

Figure 1.2 adapts what is presented in Figure 1.1 to show the general course of development in emergent approaches to case studies. In the diagram, the definition of the research question(s) is decoupled from the conduct of the literature review. The research questions are not seen as unimportant – indeed, they remain central to the construction of the case and are likely to guide many actions; however, there is acknowledgement of the possibility that ‘the best research questions evolve during the study’ (Stake, 1995: 33). Thus, in the diagram, the definition of the research question(s) could take place at a range of stages, both before or after each of the respective stages of reviewing the literature, designing the study, collecting the data, preparing for further study and collecting more data or analysing data. It will all depend on what knowledge – either formal propositional or experiential, empathetic and tacit – you have already acquired and the extent to which you have identified a phenomenon as a problem. As the diagram illustrates, there may be considerable movement backwards and forwards between different stages and some might overlap. For example, the identification of an initial problem could lead to a provisional design of a study and even the collection of some data to check that the problem may be significant simultaneous to an initial literature review, leading to a refined definition of the research question...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Authors

- About the Series Editors

- Editors’ Introduction to the Mastering Business Research Methods Series

- 1 Introduction to Case Studies

- 2 Understanding Case Studies

- 3 Basic Components of Case Studies

- 4 Conducting Case Studies

- 5 Examples of Orthodox and Emergent Case Studies

- 6 Conclusions

- Glossary

- References

- Index

- Publisher Note