- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Visual Methods in Social Research

About this book

The Second Edition of this popular text confirms the book's status as an important forerunner in the field of visual methods.

Combining the theoretical, practical and technical the authors discuss changing technologies, the role of the internet and the impact of social media. Presenting an interdisciplinary guide to visual methods they explore both the creation and interpretation of visual images and their use within different methodological approaches.

This clear, articulate book is full of practical tips on publishing and presenting the results of visual research and how to use film and photographic archives.

This book will be an indispensable guide for anyone using or creating visual images in their research.

Combining the theoretical, practical and technical the authors discuss changing technologies, the role of the internet and the impact of social media. Presenting an interdisciplinary guide to visual methods they explore both the creation and interpretation of visual images and their use within different methodological approaches.

This clear, articulate book is full of practical tips on publishing and presenting the results of visual research and how to use film and photographic archives.

This book will be an indispensable guide for anyone using or creating visual images in their research.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Reading Pictures

Figure 1.1 Christmas 2008: local photographer at work in Somié Village, Cameroon.

1.1 The trouble with pictures

Anthropology has had no lack of interest in the visual; its problem has always been what to do with it. (MacDougall 1997: 276)

It used to be quite common for visual researchers in the social sciences to claim that they work in a minority field that is neither understood, nor properly appreciated by their colleagues (e.g. Grady 1991; Prosser 1998b; cf. MacDougall 1997). The reason, the argument went, is that the social sciences are ‘disciplines of words’ (Mead 1995) in which there is no room for pictures, except as supporting characters. Yet today, interest in visual analysis seems to be growing widely in the social sciences. Visual anthropology leads the way in this, although visual sociology is also a relatively well-established sub-discipline, and visual approaches can be found in other research areas such as social psychology, educational studies and the like.1

There is now an abundant research literature from within cultural studies and most social science disciplines that specifically addresses visual forms and their place in mediating and constituting human social relationships, as well as discussing the visual presentation of research findings through film and photography. Until recently methodological insight has been, however, scattered or confined to quite specific areas, such as the production of ethnographic film.2 Paradoxically, while social researchers encounter images constantly, not merely in their own daily lives but as part of the texture of life of those they work with, they sometimes seem at a loss when it comes to incorporating images into their professional practice.

1.2 An introductory example

Figure 1.2 Early to mid twentieth-century postcard.

Photographer unknown.

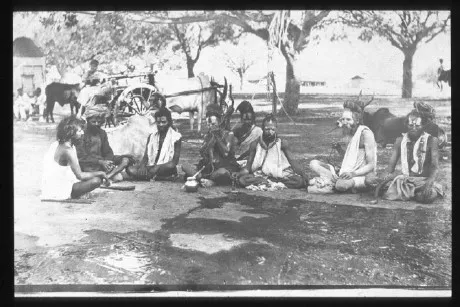

So, what can social researchers do with pictures? Take Figure 1.2. It is a photograph, clearly. Eight men sit in a rough line, cross-legged, on the ground about 2 metres or so from the camera. Behind them are some trees, a cart with an ox yoked to it and on the far left of the picture some sort of small structure in front of which sit two other men. The men in the central line are oddly attired – some have white cloths draped across their shoulders but otherwise appear naked except for loin cloths. The faces of some are whitened with paint or ash; they are all bearded and some appear to have long hair gathered up on top of their heads. Several of the men are looking at the camera, and one holds something up to his mouth.

So far, assessing the content of the image has been a matter of applying labels – ‘man’, ‘cart’, ‘cloth’ – which lie within most people’s perceptual and cognitive repertoire, as does the assessment of spatial arrangements: ‘in a line’, ‘to the left of’, ‘behind’. To go much further in a reading of the image requires more precise information. The ox cart, for example, indicates that the scene is probably somewhere in South Asia, while anyone with a familiarity with India will probably guess that these are some kind of Indian ‘holy men’. More specifically, they seem to be Hindu sadhus or ascetics. The man second from the left is actually not attired like the rest – he wears some kind of shirt or coat, and a turban. He is perhaps a villager who has come to talk to them or a patron who gives them alms. Those with more knowledge of Hindu practice may be able to highlight further detail, relating to the patterns of white markings on their faces, the just visible strings of beads some of them wear. Other areas of knowledge might enable us to identify the particular species of trees in the background or the specific construction type of the cart, helping us to guess at the altitude or region. Clearly it is not merely a question of looking closely but a question of bringing various knowledges to bear upon the image.

While such a reading may help us towards understanding what the image is of, it still tells us nothing about why the image exists. To do that, we must move beyond the content and consider the image as an object. It is in fact a postcard, printed upon relatively thick and rather coarse card. The image itself is a photomechanical reproduction, not a true photograph, and although apparently composed of a range of sepia tones, this is an illusion, with only brown ink – in dots of varying size – having been used.

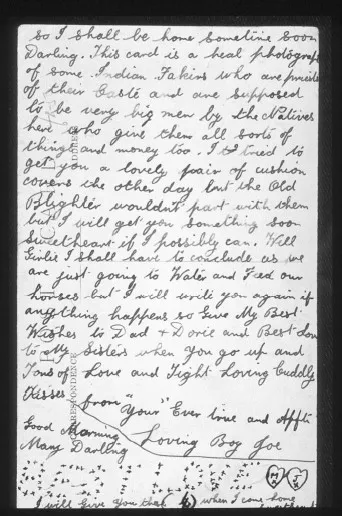

The reverse is marked in two ways (see Figure 1.3). First, the words ‘Post Card’, ‘Correspondence’ and ‘Address’ are printed lightly along the long edge. Secondly, these words are almost completely obscured by handwriting, which reads:

so I shall be home sometime soonDarling. This card is a real photographof some Indian Fakirs who are priestsof their Caste and are supposedto be very big men by the Nativeshere who give them all sorts ofthings and money too. I tried toget you a lovely pair of cushioncovers the other day but the OldBlighter wouldn’t part with thembut I will get you something soonSweetheart if I possibly can. WellGirlie I shall have to conclude as weare just going to Water and Feed ourhorses but I will write you again ifanything happens so Give My BestWishes to Dad + Doris and Best Loveto My Sisters when you go up andTons of love and Tight Loving CuddlyKissesfrom“Your” Ever true and Afft Loving Boy Joe Good MorningMary DarlingBEST LOVEI will give you that ([pointer to the words ′best love’]) when I come home Sweetheart

Figure 1.3 Reverse of postcard reproduced in Figure 1.2.

So, it is a postcard from Joe to his wife or fiancée Mary. There is no address or stamp and indeed the message appears to be only partial (‘so I shall be home sometime soon…’ seems to follow on from some previous statement) and perhaps the letter was begun on ordinary paper and the whole posted in an envelope. But there is now a completely different reading, one that ties the image’s narrative to Joe’s narrative. Joe’s ‘real photograph’ is a print, not a real photograph, but by ‘real’ he seems to mean ‘there really are people and places that look like this’: he knows what he has seen. He is less sure about what it means – the men are called ‘Fakirs’ and are priests, but they are only ‘supposed’ to be big men. He knows they are given money, which reminds him that he tried to give someone money but the ‘Old Blighter’ wouldn’t accept it, and so on. MB’s own guess is that Joe was a soldier, serving in India towards the end of the Second World War – his mention of the cushion covers reminds MB of a crewel work bag that his own father brought back from Bengal for his mother, subsequently passed on to his wife (MB’s mother), when he was stationed in India with the RAF in the late 1940s.

Now that we have a (partial) reading of the image it remains to sociologize it, to place that reading within the context of a particular social research project. To follow up the story of the ‘Indian Fakirs’ would require some detailed research in picture archives and museums, perhaps trying to trace the company that produced the postcard and then using ethnological and Indological research to identify the sadhus, or at least their sect. By the end, one might have uncovered enough information possibly to locate the sadhus – or at least people who knew them. One could then use the image, and any others if the postcard were part of a series, in the course of an anthropological or religious studies research project. In the course of fieldwork in India with contemporary Hindu sadhus one could produce the postcard during interviews to prompt memories and reflections on the part of the sadhus about changes in Hindu asceticism over the last half century.

Alternatively, there is another story to follow: that of Mary and Joe. Initially the research might follow similar lines: use archival resources to trace the postcard, and to establish where and when it might have been sold. Then Army records may be used to try and establish which regiments might have been in that area at that time, and so on to try and locate Joe. (In truth, identifying the individual sadhus is probably easier than trying to identify Joe.) The image could then be used as part of a research project in British social history – together with other images and letters sent by soldiers overseas to family and loved ones – to assess the role of British women and how they lived their lives at home while their menfolk were away. Did new brides and fiancées maintain closer ties than normal to their female affines or affines-to-be, for example (‘Best love to my Sisters when you go up’)?

A third line of enquiry also presents itself. MB bought the postcard at a sale of postcards, cigarette cards, telephone cards and other collectable ephemera in a village hall near his home in Oxford a few years ago. It had travelled half way around the world, passed through many people’s hands, and is now in Australia, where MB sent it as a gift to a friend. The postcard cost £1.50, a price at the lower end of the scale in such sales: a seller said that serious postcard collectors prefer mint condition cards, without writing, stamps or franking. Clearly, we are not the only ones interested in old postcards, such postcard fairs are common – with the cards sorted by geography (the one above was in the ‘Ethnic’ category, but postcards of the British Isles are meticulously subdivided by county and town) or types (‘Animals’, ‘Flowers’, ‘Famous People’). Nor are we the only ones interested in antiquarian images of non-European peoples, although the majority are well beyond our price range: a good early photograph by a named photographer of non-European people, especially Chinese, Japanese and Koreans, or Native Americans, can easily cost £500 and beyond. A set of such images in an elegant album can cost over £10,000. A sociologist, an economist, or an art historian could each construct a research project enquiring into cultural value and market forces in venues ranging from humble village halls to the salerooms of London and New York auction houses.

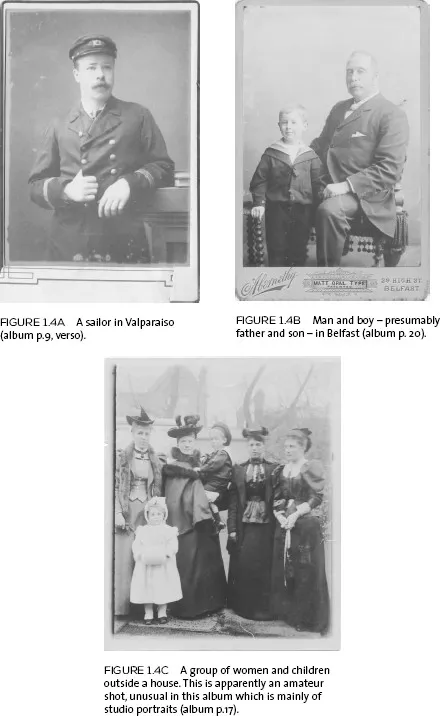

Figure 1.4 Three images from a C19th album

These different possible research methods apply to individual images but also to collections of images. Consider old-style photo albums (and their contemporary online analogues). All the approaches we have just described could be applied to each individual image in an album. There are also some new questions which apply to the collection as a whole. For example, the location where a photograph was taken may be of interest in itself but it has a different sort of meaning in an ensemble. In one case in point DZ purchased an old album in an antiques shop in east Kent in the 1990s. On the basis of a few names written on the backs of a few prints we infer that this was possibly made by a member of the Gossage family. However, it lacks virtually all means of identifying most of the people depicted, so the location of the commercial photographers who made the prints provides a clue as to the home town of the album’s owner: since 21 of the 57 images were made in Liverpool and its surroundings (in north west England) it seems reasonable to infer that this is the home town of the family whose life is depicted in the album. Among exceptions are holiday locations and some from port towns round the world including Valparaiso in Chile. This suggests that at least one family member was in the merchant marine. Albums or similar collections are curated: someone has chosen which images to include and in which order, whether to add captions and if so of whom? Are servants and pets named as well as the family members? Are there consistent patterns of posing identifiable between images? Although the people who maintain these collections may not think of their activity as one which resembles the activity of professionals managing museums or arranging exhibitions, methodologically we think it is helpful to explore the parallel and to treat the album bearers as curators. Often in European and North American traditions keeping albums and being the family historian are shared tasks and ones undertaken by women: gender issues cannot be ignored. At a later stage early in the twentieth century when family photographs were taken by amateur photographers within their family (but before self timers were common) the one person who may be missing from the images in an album is the father/husband/patriarch: the man behind the lens (see also the discussion of Geffroy’s [1990] work with French family photography in Section 2.4.2).

All of the issues touched upon above, and many more besides, are examined in more detail in the course of this book, following the lines of enquiry produced by ‘found’ images such as the postcard and album opposite, as well as images created by the social researcher. In broad terms social research with pictures involves three sets of questions: (i) what is the image of, what is its content? (ii) who took it or made it, when, how and why? And (iii) how do other people come to have it, how do they read it, what do they do with it? These questions may be asked whether the images are on paper (analogue) or digital. Some of these questions are instantly answerable by the social researcher. If she takes her own photographs of children playing in a schoolyard, for example, in order to study the proxemics of gender interaction, then she already has answers to many of the second two sets of questions. The questions may be worth asking nonetheless: why did I take that particular picture of the boy smiling triumphantly when he had pushed the girl away from the slide? Does it act as visual proof of something I had already hypothesized? How much non-visual context is required to demonstrate its broader validity? And so on. Sometimes – perhaps quite frequently – our initial understandings or readings of visual images are pre-scripted, written in advance, and it is useful to attempt to stand back from them, interrogate them, to acquire a broader perspective.

1.3 Unnatural vision

Seeing is not natural, however much we might think it to be. Like all sensory experience the interpretation of sight is culturally and historically specific (Classen 1993). Equally unnatural are the representations derived from vision – drawings, paintings, films, photographs. While the images that form on the retina and are interpreted by the brain come in a continual flow, the second-order representations that humans make when they paint on canvas or animal skin, or when they click the shutter on a camera, are discrete – the products of specific intentionality. Each has significance by virtue of its singularity, the actual manifestation of one in an infinitude of possible manifestations. Yet in Euro-American society we treat these images casually, as unexceptional presences in the world of material goods and human social relations.

This is partly because for centuries vision – sight – has been a privileged sense in the European repertoire, a point well-established by philosophers, social theorists and othe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About The Authors

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Acknowledgements

- Image Credits

- 1 Reading Pictures

- 2 Encountering The Visual

- 3 Material Vision

- 4 Research Strategies

- 5 Making Images

- 6 Presenting Research Results

- 7 Perspectives On Visual Research

- References

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Visual Methods in Social Research by Marcus Banks,David Zeitlyn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.