![]()

SECTION 1

Establishing the

Framework

![]()

1

Why Does Social Psychology Need a Cross-Cultural Perspective?

‘The only true exploration, the only true fountain of delight, would not be to visit foreign lands, but to possess others’ eyes, to look at the world through the eyes of others.’

(Marcel Proust, The Prisoner and the Fugitive, 1905)

Two English-speaking acquaintances meet on a street corner. ‘How are you?’, says one. ‘Terrific’, replies the other, ‘how about you?’ ‘Not too bad’, says the other. From this conventional interchange, we can infer that the first speaker is probably US American and the second is probably from one of the other Anglo cultures around the world, such as the UK, Australia or New Zealand. They both speak the same language, but the norms guiding opening self-presentations will differ even between these two relatively similar cultural groups. A distinctive aspect of US culture is the value placed on expressing oneself positively, which is not found to the same extent in all other parts of the world. For instance, Kitayama, Markus, Matsumoto, and Norasakkunkit (1997) found that American students reported being more often in situations that led to feeling positive about themselves, whereas Japanese students reported being more often in situations where they felt critical of themselves. Furthermore the Americans were more likely to feel positive even in situations where the Japanese did not.

Of course we cannot be sure about the nationality of either party in our imaginary exchange of greetings, because there is tremendous individual variability within any large cultural grouping, and there is also some variability in how a given person chooses to present him- or herself on any specific day. Nonetheless, there are reliable cultural differences around the world in how people do relate to one another, and these differences pose challenges that are increasingly important in a globalising world. If we as social psychologists are to understand these challenges, and provide effective help in facing them, we need to do so in terms of theories and findings that are based on an adequate understanding of cultural variability.

In this book we will outline a social psychology that can help us to understand and cope with the unparalleled processes of social change that are occurring in the world at the present time. This book has three sections. In the first, we lay the conceptual groundwork. In the second, we address major areas of social psychological study. In the third, we consider some major contemporary issues where culturally informed social psychologists can make a contribution. We conclude each chapter with a summary, suggestions for further reading and some study questions. We have also provided a glossary at the end of the book, in which you will find definitions of the technical terms that have proven useful for cross-cultural social psychologists. Terms that are included in the glossary appear in bold when they are first mentioned.

Formulating a social psychology that can address a changing world will not be an easy task, as it requires us to focus equally on two important issues that are most often kept quite separate: whom we should be studying, and how we should make sense of social change.

WHOM SHOULD WE BE STUDYING?

Firstly, we need to show how social psychologists can address the diversity of the world’s population. Social psychology has most frequently been conducted by focusing on standardised and simplified settings. This type of focus can yield a sharply delineated understanding of what occurs within the few types of setting that are mostly sampled, but it raises problems if we wish to apply those understandings to more everyday settings, especially those that are located in different cultural contexts.

Arnett (2008) reported that in recent issues of six top US psychology journals 68% of samples were from the US and a further 28% were from other Western, industrialised nations. The final 4% were drawn from the rest of the world, whose population makes up 88% of the total world population. As Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan (2010) neatly summarised the situation, social psychology is WEIRD – in other words, it has mostly been based on studies of people from the relatively few nations that are Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic. Even within those nations its research findings have mostly been based on studies of relatively young persons who are attending university, and especially on those who are also unusual because they are studying psychology.

Studies on this basis would only be a reliable guide to social behaviour in the rest of the world if people and the ways that they relate to others were much the same everywhere. So where do you, the reader, fit into this pattern? Are you from one of the WEIRD nations, or are you from what KağıtçıbaŞı (2007) calls the Majority World, namely the much larger portion of human-kind that is not WEIRD? And how does your situation affect how you think about cultural differences in social behaviour?

Later in this chapter, we examine the evidence showing that studies conducted in different parts of the world often yield different results. In Chapter 2, we then look at how this variability can be systematically described and explained. In Chapter 3, we examine ways in which different cultures have arisen and sustained themselves over the centuries, while also accommodating increasing globalisation. These early discussions raise questions as to how cross-cultural studies can be done in valid ways, and Chapter 4 provides guidelines on how to identify and conduct studies that can best meet these challenges.

UNDERSTANDING SOCIAL CHANGE

Our second major issue is that in the modern world we need to focus on change as much as on stability. Research methods that sample events at a single point in time, as most do, can give us an illusion of social stability, even though our individual experiences tell us that things are in flux. In the central section of this book, we go along with the convenient assumption that we are studying a stable world, in order to provide a cross-cultural perspective on some of the major topics of social psychology. In the third section, we then focus on the ways in which social psychological perspectives can be applied to contemporary issues that are being triggered by increasing cross-national contact through the travel, education, migration, electronic media and trade that have been unleashed by globalisation.

Our focus can be introduced in a few paragraphs. Over the past 10,000 years, human evolution has differentiated a series of relatively small and relatively separate groups that we can describe as societies or cultures. These cultures were adapted to sustaining life in a wide variety of differing and often hostile environments. Depending on how we might choose to define ‘culture’, several thousand cultures may be considered to have evolved. In the early part of the twentieth century, social anthropologists made detailed ethnographic studies of many of these groups. Their observations have been documented and summarised in the ‘Human Relations Area Files’ at Yale University, which contain information on 863 cultural groups (Murdock, 1967).

Some of the earliest of these anthropological investigations also involved psychologists. Over 100 years ago, a group of social scientists visited the islands in the Torres Straits which separate Australia and New Guinea. One member of the team, the psychologist William Rivers, focused his studies upon the islanders’ perceptual processes. You can see an account of some of his experiences in Everyday Life Box 1.1. Look also at the results that he obtained, which are described in Key Research Study Box 1.1.

Some of the early anthropologists also employed psychological terms to describe the whole cultures that they studied and explain the social processes that characterised them. This approach became known as the ‘culture and personality’ school of thought (Benedict, 1932). For instance, drawing on this perspective, Benedict (1946) asserted that the national character of the Japanese was based on shame, in contrast to that of Western nations that was based more on guilt. She acknowledged that some individuals might not fit the overall pattern, but was primarily concerned with understanding the overall profile of a given society. As is often the case in cultural work, there was a powerful motivation for providing such an understanding – in this case Japan, an unknown foe, had just entered the Second World War against the United States, and the US War Office was eager to know how to deal with its enemy.

This perspective subsequently fell out of favour, partly because it assumed that most members of a culture shared the same personality and partly because there were no established personality measures at the time (Piker, 1998). As we shall see in Chapter 5, there is now some evidence of cultural variability in the distribution of personality traits, but there is also much variability between individuals. To explain social behaviour, we will need to understand both types of variation.

Everyday Life Box 1.1 The Torres Straits Expedition

In 1898, a team from Cambridge University visited a set of islands in the Torres Straits, which lie between Australia and New Guinea. The team included three psychologists, of whom the leader was W.H.R. Rivers. Their purpose was to test the hypothesis that, while ‘savages’ were lacking in higher mental functions, they had superior visual skills. Their studies were impeded by the failure in this very different climatic context of many of the types of psychological apparatus that they had taken with them. Rather than working in a controlled laboratory setting, studies took place in the open with an appreciative audience of spectators. The way in which they explained their studies conveyed strong demand characteristics:

The natives were told that some people had said that the black man could see and hear better than the white man, and that we had come to find out how clever they were and their performances would all be described in a big book, so that everyone would read about them. This appealed to the vanity of the people and put them on their mettle… (Rivers, 1901, cited by Richards, 2010)

One research assistant further encouraged participation by telling islanders that if they did not respond truthfully, Queen Victoria would send a gunboat. The ‘control’ samples from which data were collected in the UK were poorly matched with the islanders, so that many of the findings must be considered inconclusive (Richards, 2010). Nonetheless, this very first cross-cultural study illustrates many of the difficulties that more recent cross-cultural comparisons must overcome if they are to yield valid conclusions.

As was normal at the time, the research team collected many cultural artefacts, which were then deposited in museums in Cambridge, UK. In 1998, a group of Torres Islanders were invited to Cambridge. The leader of this group expressed pleasure that these artifacts had been preserved, as they had great symbolic meaning, and were no longer found in the Torres Straits islands. Discussions ensued as to where the artifacts should now be located.

The fact that anthropologists were able to visit and document all these cultural groups was itself a symptom of an evolutionary process that commenced long before the industrial revolution and has been accelerating ever since. The development of modern technology has steadily increased the speed and ease with which we can travel the world and has virtually eliminated the time within which messages can pass between two points located anywhere on the globe. New technologies and the economic developments that these have engendered have increasingly unleashed a new ‘anthropocene’ stage in earth’s history (Ruddiman, 2003). This encompasses the period during which human activity has started to affect the global environment. Ruddiman argues that this began with the invention of agriculture, but its effects have become particularly marked over the past two centuries.

Key Research Study Box 1.1 Visual Illusions

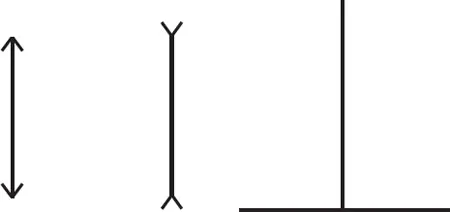

Despite whatever preconceptions the researchers of the Torres Straits Expedition may have held, they obtained some rather striking results. In particular, they reported that the susceptibility to visual illusions varied, depending on the perceiver’s ethnicity. The islanders were less susceptible than British respondents to the Müller-Lyer illusion, namely the false perception that the vertical lines with outward and inward facing arrow heads in Figure 1.1 differed in length. However, they were more susceptible than Caucasians to the illusion that the vertical line in Figure 1.1 was longer than the horizontal line.

Ethnicity/Ethnic Group Ethnicity is a problematic concept widely used in some parts of the world to identify sub-cultural groups on the basis of criteria such as ancestry, skin colour and other attributes. A person’s self-identified ethnic identity does not always coincide with his or her ethnicity as identified by others.

Figure 1.1 Visual Illusions

Susceptibility to various types of visual illusions has been studied extensively by cross-cultural psychologists in more recent times (Segall, Dasen, Berry, & Poortinga, 1999). The Müller-Lyer illusion is found in societies in which people live in houses with upright walls and square corners. The results are not wholly consistent, but it appears that differential sensitivity to illusions is a product of the particular type of environment in which one lives. The presence or absence of particular types of routine visual stimuli in the environment is thought to give differential encouragement to the development of relevant types of perceptual discrimination.

Rivers and his colleagues used a great variety of tests, not just those that have been mentioned here. He was perhaps lucky, in that they chose to include two different tests of visual illusion. Had they used only one, they might have been led toward a false and possibly racist conclusion about the greater susceptibility of one group to illusions.

Many of the several thousand languages that have evolved out of distinct cultural niches and traditions are in the process of being lost. In parallel with this reduction in linguistic diversity, a few languages are becoming more and more widely spoken. Most of the cultural groups studied earlier by anthropologists are no longer insulated from external influences and many have disappeared in the form first described by anthropologists. Mass media ensure that the cultural products of a few industrialised nations are beamed into all corners of the world. Very large numbers of persons visit other parts of the world, as tourists, as workers for either non-governmental organisations or foreign governments, as students or for business purposes. Large numbers of persons migrate to other parts of the world, some as foreign workers, some as economic migrants, and some as refugees or as victims of political or religious persecution. Even larger numbers of people are moving from the countryside to ever growing cities, with the proportions of humans living in cities rising from 29% in 1950 to 50% today, and expected to reach 69% by 2050 (United Nations, 2010).

So how can we best understand these processes of social and cultural change and stability? The world is now organised as a system not of thousands of cultural groups, but of slightly more than 200 natio...