![]()

PART I

Theory and context in mental health nursing

![]()

1

Theoretical Perspectives in Mental Health Nursing

Steven Pryjmachuk

What will I learn in this chapter?

The aim of this chapter is to introduce you to the various, often competing, theories and perspectives that have had an influence on contemporary mental health nursing practice. In doing so, it will be necessary to explore the interrelated concepts of ‘mental health’ and ‘mental illness’, and to look briefly at the history of mental health nursing, its current state of play, and the directions it may take in the future.

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- differentiate between the concepts of mental health and mental illness and explain the interrelationships between the two;

- appreciate how the history of mental health nursing impacts on contemporary mental health nursing practice;

- compare and contrast the variety of competing theoretical perspectives that underpin mental health nursing practice, making particular reference to their respective evidence bases;

- reflect upon the questions surrounding mental health nursing’s future direction.

Introduction: What Is Mental Health?

You are obviously reading this because you have an interest in mental health nursing (or, at the very least, mental health), but what exactly is mental health? And why does this book and much of current parlance refer to mental health nursing and not psychiatric nursing? Indeed, those practising in this area who are on the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s statutory register find themselves officially (and legally) Registered Nurses, Mental Health and not ‘Registered Psychiatric Nurses’. Hopefully, you will find some answers to these questions in this chapter although, as a critical reader (which is what we want modern mental health nurses to be), you do not necessarily have to agree with those answers.

To return to our principal question – what is mental health? – take a few moments to consider the questions below.

Reflection Point

Mental health and ill-health

How do you know if you are mentally healthy? What factors do you think influence someone’s mental health?

What’s the relationship between ‘health’ and ‘illness’? Is it possible to define illness without defining health or to define health without knowing what illness is?

One answer to our principal question is provided by the World Health Organisation, which defines mental health as ‘a state of well-being in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’ (WHO, 2001). In using the World Health Organisation’s definition to answer our principal question, we may have opened a can of worms however. Consider the reflection point below.

Reflection Point

Stress and coping

So, according to the World Health Organisation’s definition, is someone mentally ‘unhealthy’ if they can’t cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively or make a contribution to his or her community?

Where does mental illness fit into this picture?

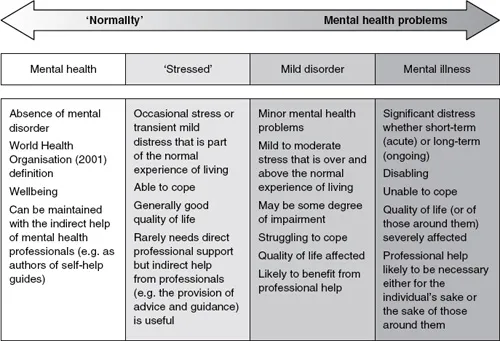

FIGURE 1.1 The mental health/mental illness continuum

One solution to all of this is to consider mental health and mental illness as the two extremes of a continuum. Such a continuum is represented by the double-arrowed bar in Figure 1.1. A continuum is essentially a link between two extremes – normality and mental health problems, in our case – where the transition from one to the other is gradual and seamless. The four discrete columns in Figure 1.1 are an attempt to integrate some commonly used terms into the continuum. Note that although there are solid lines between the discrete columns in Figure 1.1, this is more about a human tendency to ‘pigeonhole’ people than about defining rigid boundaries between categories. Indeed, it can be very difficult at times to distinguish between the categories, especially at the boundary points: at what point does ‘stressed’ become a mild disorder and mild disorder become a mental illness, for example?

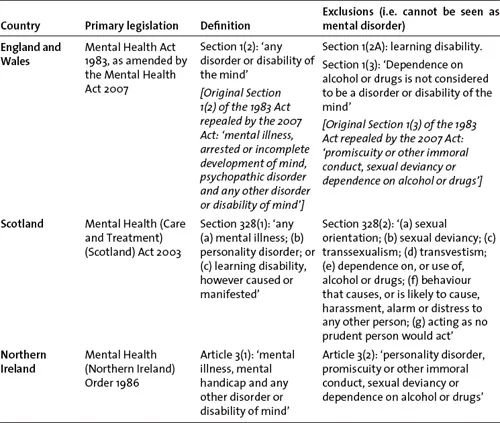

The right-hand side of the continuum in Figure 1.1 is associated with terms like ‘mental illness’, ‘mental health problems’ and ‘mental ill health’; terms that are used throughout this book. Another term that fits in with this side of the continuum and one to which we need to give special consideration is mental disorder. It needs special consideration because United Kingdom (UK) law uses it to determine who should be forcibly treated or detained under mental health legislation. All four countries of the UK use the term in this way, though its definition varies from country to country (see Table 1.1); learning disability, for example, is a mental disorder in Scotland and Northern Ireland but not in England and Wales.

TABLE 1.1 Definitions of mental disorder across the countries of the UK

We can also make some comments about the roles that mental health nurses can play as we move along the continuum outlined in Figure 1.1. While most people would expect mental health nurses to be involved in helping people on the ‘mental health problems’ side of the continuum, many are surprised to find (and you may be too) that mental health nurses can be – indeed, are – involved in assisting and supporting people with no history of mental health problems in the maintenance of their mental health. They might do this via various mental health promotion activities, be they direct (such as planning and running work-based stress management programmes or working in a primary care service such as a GP clinic or NHS Direct) or indirect (such as authoring self-help guides in relation to stress or ‘common mental health problems’ like anxiety and depression). This important aspect of mental health nursing is often overlooked, perhaps because of the dominant stereotypes relating to what mental health nurses do – stereotypes that almost always involve the dishing out of medication or dealing with disturbed individuals in straitjackets. At this point, it’s appropriate to consider where some of these stereotypes may have come from by looking briefly at the history of mental health nursing.

The History of Mental Health Nursing

Attendant or nurse?

The history of British mental health nursing is intrinsically tied up with the history of psychiatry. The turning point in psychiatry (hospital psychiatry, at least) was the passing, in England and Wales, of the interrelated and interdependent Lunacy and County Asylums Acts of 1845. These Acts set up the Lunacy Commission, a body Roberts (1981) refers to as the ‘The Victorian Ministry of Mental Health’. The Lunacy Commission established an obligation for local authorities (the counties and boroughs of the time) to provide asylums for ‘pauper lunatics’, that is, those without the financial means to obtain care in the privately run madhouses. The Lunacy (Scotland) Act of 1857 underpinned a similar growth in the number of public asylums in Scotland. Interestingly, and in contrast to England and Wales, the Scottish lunacy act formalised the practice of boarding-out to the community the ‘harmless and chronically insane’ (Sturdy & Parry-Jones, 1999), a practice that was, to some extent, a precursor to modern-day community care. Northern Ireland has a shorter history in terms of mental health policy since the province only came into being as a political entity in 1921; prior to 1921, most of Northern Ireland’s mental health policy was rooted in the lunacy legislation of pre-partition Ireland (Prior, 1993).

The Lunacy Acts of the mid-nineteenth century essentially created an institutional base for the emerging discipline of psychiatry (Nolan, 1998). Prior to these Acts, those looking after the mentally ill were often referred to as ‘keepers’, a somewhat dehumanising term (think about it: keepers are often associated with collections of some sort, be they animals or objects). After these Acts, the more humane term attendant became a more prevalent description of those who undertook the day-to-day work in asylums. The explicit link with nursing started to come about owing to the fact that female attendants were often referred to as nurses and that formal training for attendants implied that nursing was part-and-parcel of what they did. For example, the Royal Medico-Psychological Association (RMPA), which would later become the Royal College of Psychiatrists, formalised training in 1891, awarding those who successfully completed training a ‘Certificate of Proficiency in Nursing the Insane’.

The RMPA’s dalliance with nursing was not without controversy, however. There was opposition from the asylum attendants themselves, who did not necessarily want to be associated with general nursing. More domineering in the debate, however, was Mrs Ethel Bedford-Fenwick, Matron of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, and the force behind a nineteenth-century drive to professionalise nursing via a statutory register. Mrs Bedford-Fenwick had already staked her claim as to what nursing was and what nurses were and her claim did not include asylum workers whom, she argued, should not be called nurses (Nolan, 1998). Since most asylum attendants were male and almost all of Mrs Bedford-Fenwick’s ‘true’ nurses were female, her objections may well have been nothing more than a gender issue (Chatterton, 2004).

Nursing councils

In 1919, Mrs Bedford-Fenwick got her way when statutory nursing registration became law and General Nursing Councils were set up for the separate countries of the United Kingdom. The animosity, evident in the likes of Mrs Bedford-Fenwick and her contemporaries, between general nurses and asylum attendants (or mental nurses as they would become known) continued in some subtle and not so subtle ways. Mental nurses, along with male nurses (who were, in turn, mainly mental nurses), were only allowed onto a supplementary – some would say, inferior – part of the nursing register, although the RMPA certificate was recognised as a means of admission to this supplementary part. Moreover, in 1925 the General Nursing Councils attempted to wrench control of mental nurse training away from the RMPA, a hostile battle that resulted in two separate systems of training operating until the post-war establishment of the NHS in 1946 (Chatterton, 2004).

Following the establishment of the NHS, the General Nursing Councils reigned supreme until the Briggs Report (DHSS, 1972) led to the Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Act 1979 which in turn led to the dissolution of the General Nursing Councils and the creation, in 1983, of the United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (UKCC) and a national board for nursing education in each of the four co...