![]()

1 | Developing the children’s workforce Rose Envy |

Reading through this chapter will help you to:

- reflect upon your own role in relation to the wider children’s workforce;

- critically appraise the skills required to work with children across a range of children’s services;

- apply your understanding of the skills required to work with children in relation to early years and identify those skills you need to develop further.

Introduction: the early years practitioner and the wider children’s workforce

The intention of this book is to provide you with an overview of the different aspects of early years practice and provide an opportunity for you to reflect upon the knowledge and skills you will need to acquire to become a successful early years practitioner. This chapter will enable you to consider the role of the early years practitioner within the context of the wider children’s workforce. Studying on an early childhood studies degree provides you with the skills and knowledge to be able to enter the children’s workforce across a range of services.

ACTIVITY 1

Think of the term ‘the children’s workforce’. What do we mean by this? Is the term said in reference only to those who work with young children, or does it include all those who work indirectly with children and their families?

The children’s workforce does not refer only to those practitioners who work in early years or teaching. All those who work with children, young people and their families are an integral part of the children’s workforce. The DCSF (2008e, p3) states that:

Everyone who works with a child or young person or with their family has a role to play in supporting their development across all five Every Child Matters outcomes – whether they work in education, health, 14–19 learning, safety and crime prevention, out-of-school activities, child care, play, community involvement or economic wellbeing.

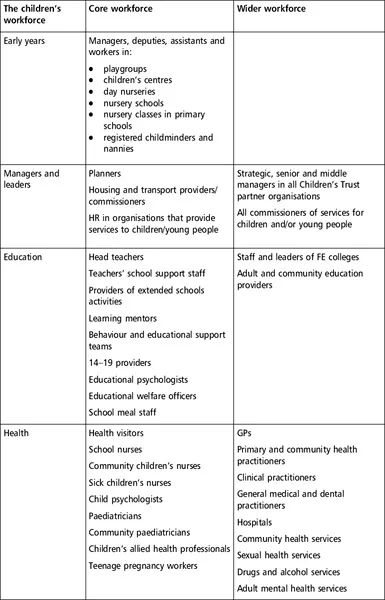

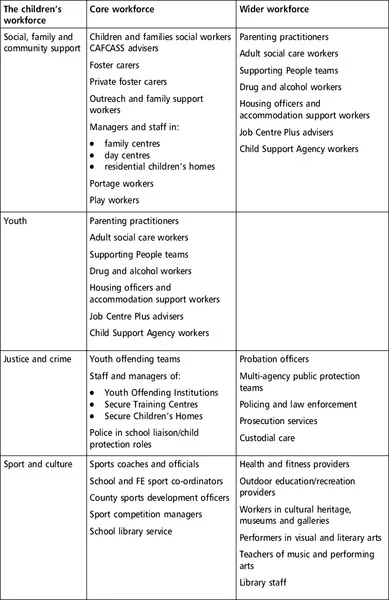

To give you a better understanding of the range of roles within the children’s workforce, Table 1.1 identifies many of the roles within each of the different services.

Table 1.1 The children’s workforce

Adapted from DCSF (2008e)

As you can see, the children’s workforce consists of both a ‘core and wider workforce’ DCSF (2008e, p10). The core children’s workforce identifies all those whose primary role is to work directly with children and contribute to improving outcomes for them. The wider children’s workforce identifies those who may not necessarily work directly with children and young people as part of their primary role, but their role contributes to improving outcomes for children and young people.

CASE STUDY 1

Gemma is an early years practitioner working in the nursery class in a primary school. Gemma, along with the nursery teacher, provides activities to promote learning and development in children aged 3–5 years in line with the Early Years Foundation Stage Framework. The activities provide opportunities to enable children to make progress towards the milestones identified in the Foundation Stage Profiles. Gemma and the nursery teacher are directly responsible for improving outcomes for the children in their care; they are therefore part of the core children’s workforce.

CASE STUDY 2

Steven is a Parent Support Adviser (PSA) working in a primary school. His role is to support parents to improve their parenting skills, to help them access the correct services they need or to give them the confidence to be able to support their child’s learning and development. Steven’s role is very diverse: he primarily works with parents, although occasionally he will work with the whole family. Rarely does he work with individual children in the absence of their parents. As a PSA Steven contributes towards improving outcomes for children, young people and their families; he is therefore part of the wider children’s workforce.

If when embarking upon your early childhood studies degree you are not quite sure of the route you would like to take, it is worth noting that early years practitioners can be employed in a range of different settings, for example: nursery classes within a maintained primary school, private day nurseries, museums, libraries or working as part of a team of specialists working within Children’s Centres, e.g. delivering stay-and-play sessions or working alongside health visitors. The opportunities available to you are endless.

ACTIVITY 2

If the ‘children’s workforce’ involves all those who work with children, young people and their families, who do you think we refer to when we say ‘the early years workforce’?

Much of the literature published recently (DfE, 2010, 2012b; DfE and DoH, 2011) refers to children in their ‘foundation years’, that is children from birth to five years of age, therefore we could assume that the early years workforce refers to those who work with children within this age group.

ACTIVITY 3

Think about the Jesuit motto, ‘Give me the child until he is seven, and I will give you the man.’ What do you think this motto suggests?

The motto in Activity 3 implies that everything a child experiences during the first seven years of life has a profound effect on their future life. This does not mean that anything a child experiences beyond the age of seven years will not affect their life; rather the motto suggests that the early years extend beyond the age of five. Indeed most early years courses, for example the Diploma in Childcare and Education, focus on children from birth to eight years of age. Therefore for the purpose of this chapter the early years workforce refers to all those who work with children from birth to eight years of age.

The early years workforce: policy and context

The publication of Every Child Matters: Change for Children (DfES, 2004a) highlighted the need for radical change in the way that services for children, young people and their families were to be delivered. DfES (2004a) advocated a more integrated approach to the way in which professionals from children’s services worked together. In addition, DfES (2004a) introduced the notion of ‘One Children’s Workforce’ wherein all those who worked with children, young people and their families shared the same vision and had the correct skills and knowledge to enable them to provide high-quality services. This vision continues to be a priority for the current Coalition government. DfE and DoH (2011, p59) states

Whatever their specialism, practitioners in the foundation years have a common commitment to children’s healthy growth and development and working with their families. Making this goal a reality requires motivated, qualified, and confident leaders and professionals across health, early years and social care committed to working closely together in the interests of children and families.

With regard to the early years workforce, since 1997 the government has prioritised financial investment in early years and childcare in order to increase the availability and quality of early years provision and to enable greater choice for parents. This included financial provision to improve the skills and knowledge of the early years workforce. Every Child Matters (ECM) (DfES, 2004a) provided the rationale for further investment in the children’s workforce. The primary aim of ECM is to improve outcomes for young children and their families. It is widely acknowledged that this will be achieved through the development of a ‘world-class workforce’ which is competent and confident in meeting the needs of young children and their families, (DfES, 2004a). The Ten-Year Childcare Strategy (DfES, 2004b) set out to radically reform the early years and childcare sector, to ensure that childcare services in England were ‘among the best in the world’. More recently, the government has made a commitment to continue to support young children in their early years stating that

All young children whatever their background or current circumstances, deserve the best possible start in life and must be given the opportunity to fulfil their potential.

(DfE and DoH, 2011, p2)

The provision of a highly qualified and well skilled workforce is paramount if this vision is to be realised. As an early years practitioner you too will play a vital role in helping this vision became a reality.

We have talked about Every Child Matters (DfES, 2004a), acknowledging the influence that this policy has had upon the development of the children’s workforce. However, since the Coalition government came into power in 2010, less emphasis has been placed on ECM. While the statutes arising from ECM remain (Children Act 2004 and Childcare Act 2006), current political thinking suggests that the terminology of ECM will change to reflect children’s achievements, insofar as ‘every child will achieve more’. Nonetheless, ECM remains one of the most important policy developments to date effecting the early years and childcare sector.

We might ask ourselves why has there been so much investment in developing the children’s workforce, especially the early years workforce?

ACTIVITY 4

Begin to consider early years practice. Why do you think it is important to invest in the development of a highly skilled and well qualified early years workforce?

Research has proven many times that the qualifications and skills of early years practitioners are a major contributory factor in determining the quality within early years and childcare provision. Munton et al. (2002) suggest that staff qualifications are one of the factors which have a positive impact on improving outcomes for children. Practitioners who are well qualified better understand the importance of promoting early years environments which provide opportunities to promote child development. The Effective Provision of Pre-school Education (EPPE) research (Sylva et al., 2004) has played a major role in influencing policy developments with regard to the development of the early years workforce. Sylva et al. argue that the quality within early years provision correlates with the quality of the workforce, particularly in relation to the level of qualifications held by staff. More recently, Nutbrown (2012) acknowledges the influence that staff qualifications have upon the quality of early years provision and recommends that the government continues to invest in the professional development of early years practitioners, particularly the development of graduates with an early years specialism. However, qualifications alone do not ensure good quality early years provision. Fukkink and Lont (2007) highlighted that both informal and formal education and training contributed to the quality of early years and childcare provision.

Therefore, once qualified it is equally important that as an early years practitioner you engage in additional continuous professional development to ensure that your skills and knowledge reflect current thinking, both in terms of policy developments and curriculum changes.

Professionalisation of the early years workforce

For decades, the early years practitioner was always viewed as ‘less professional’ than others working in the area. Taggart (2011) argues that the general perception of the early years workforce was that it was solely concerned with the ‘care’ of young children rather than their education, and by virtue of this was perceived as ‘less professional’ than other caring professionals such as nurses. DfE and DoH (2011) also acknowledge the disparity between the professional status of those working within the early years workforce, insofar as some teachers viewed the early years practitioner less favourably than their ‘teaching’ peers, a view further supported in Simpson (2010, p10). The perception that the early years workforce was ‘less professional’ was perpetuated by the lack of a clear career structure and low rates of pay in comparison to other professions. However, when the Labour Party came to power in 1997, a concerted effort was made to radically reform the children’s workforce, including the early years workforce, to enable the government’s vision to have a ‘world-class workforce’ to be realised. The Ten-Year Childcare Strategy (DfES, 2004b) outlined the government’s aspiration to have a graduate leading early years practice in every children’s cen...