Introduction

This book is not about following recipes, but about learning the art of creating your own. As great chefs, we need skills to choose, prepare and mix our ingredients as well as knowledge transmitted by our discipline to create new recipes. The creative process is endless. Qualitative research is a never-ending journey. There are always new phenomena to learn about, new methods to invent and new forms of knowledge to create.

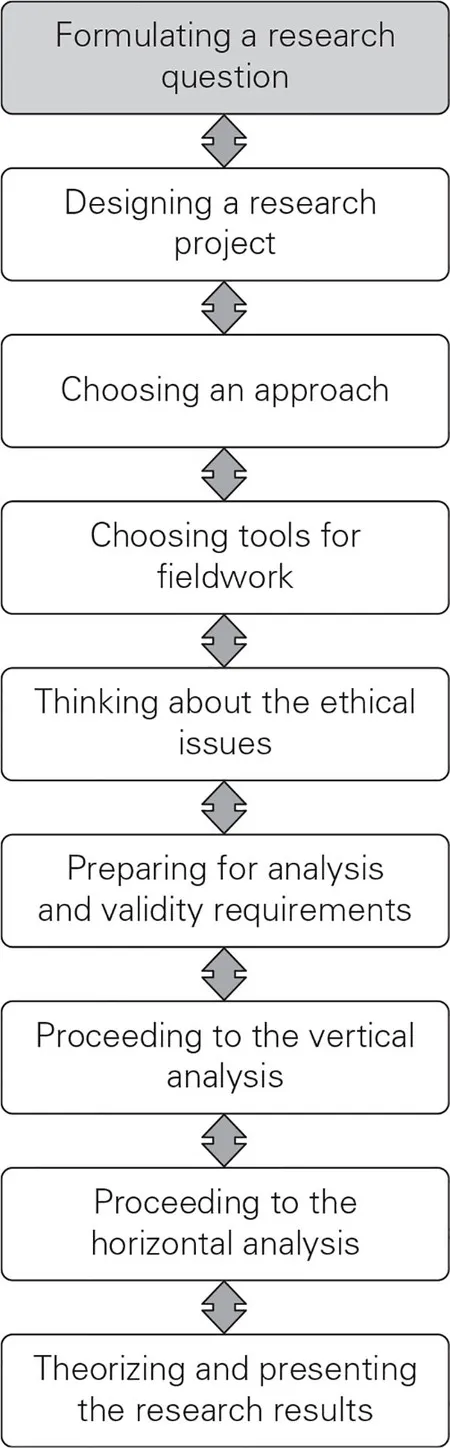

The social is your object of study. Because it is complex, dynamic and inter-subjective, we believe it calls for a specific type of research design. In this first chapter, our aim is to help you design your project on the foundation of an iterative process. That is, a research activity that continuously moves from the empirical basis of your study up to its theoretical apparatus and down again to the empirical basis. In short, there is a continuous dialogue between research material and theoretical aspects of the research project.

In this chapter, we will address three important elements of your qualitative research project: (1) your ontological and epistemological beliefs; (2) their connections to your research question; and (3) the iterative-driven research process of a qualitative scientific production. In more epistemological terms, we are inviting you to understand the realm of knowledge production you are most comfortable working in: realist, constructionist or constructivist epistemology.

You might ask yourself: why are we discussing these theoretical questions at the beginning of a book on methodology? Talking about methodology is talking about how we observe reality, how we describe it, and how we create and organize our descriptions and explanations of social phenomena. Methodology is the reflection on methods, which are tools to observe the world. Moreover, methodology contributes to the creation of scientific knowledge. That is why it is so important to understand what is being created while using qualitative methods.

The Knowledge Production Process

Creating Knowledge is Enacting the Social

By questioning and explaining the social, researchers are enacting it. This is a huge responsibility and an incredible experience of creative thinking! Because of the historical and dynamic world we try to describe, understand and explain, it is very difficult (and not necessarily desirable) to create knowledge labeled as universal. By that, we mean producing explicit laws explaining the production of a phenomenon. For example, in natural science, we observed several times that the boiling point of water is 100°C. We can now predict, based on a universal law that water will evaporate at 100° C. It is almost impossible to find such a universally valid causal relationship in the social world among a situation (temperature), an element (water) and their consequence (evaporation).

Causal relationships are established in natural science by the observation of repetitions in an experiment.

Until now, no social scientist has succeeded in identifying such universal laws because the characteristics we observe differ significantly from those of nature. It is historically situated, it is a complex object, it can take several meanings and it is based on subjective relationships. It doesn’t mean that there is no causality in social sciences. It means that causality has a different meaning. It is not a relationship based on constant consequences between element A and B as in natural science. It means that A is part of the process by which the phenomenon is produced.

In social sciences, a cause is an element that belongs to the constitution of the phenomenon. (Campenhoudt and Quivy, 2011)

Defining the ‘social’ is the cornerstone of any social science project. No one has the same answer, but many would agree that what is social is what results from relationships: relationships among humans, and among humans and non-humans. Also, social phenomena are historically situated. Thus, they remain mostly singular. They are created through relationships over time, shaped by the legacies of the generations, institutions and organizations that characterize particular societies. For example, the experience of being a female prisoner in a specific country is historically shaped by the laws, the prisons as architectural realities, the social policies and the training of the professionals working with that prisoner. That ‘prisoner’ depends on the institutional research (university and government) and the accumulated knowledge transmitted through the training and personal experience of those professionals.

The complexity of the social does not mean we cannot produce any knowledge about it. Many social scientists help us to develop a better understanding of our world. They create localized knowledge, knowledge that does not aspire to be universal but rather contextual to a time and a place and situated. It helps to improve society through better public policies, public programs or interventions. This localized knowledge leads us to enact the social. For example, we create social realities by naming, describing and interpreting them. Creating new understandings of social realities can sometimes help to deconstruct taboos and empower people. Sometimes new solutions come with new interpretations of problems.

Because we enact the social, we have a responsibility both to ensure the validity and to identify the limitations of the knowledge we produce. As qualitative researchers, we first need to admit that the knowledge we produce cannot explain straightforward causal relationships. Thus, the value and strength of the qualitative inquiry is to ‘provide a rich understanding of complex social contexts – not its ability to provide a causal explanation of events’ (Pascale, 2011: 40).

Interpretation and Explanation of Scientific Knowledge Production

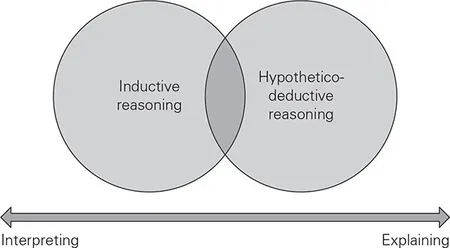

Any scientific knowledge production implies both explanation and interpretation of a particular phenomenon. For Bourdieu, interpretation and explanation are linked and might even occur concurrently (Bourdieu et al., 1983). For a pedagogical view, we will distinguish them as two ideal objectives of knowledge production. We would define an explanation as the demonstration of relationships between things, such as patterns or recurrences. Explanations are based mostly on a hypothetico-deductive process of knowledge production. Explanations based on statistical generalization are often considered more suited to objects observed in nature and less pertinent to the analysis of historical phenomena. However, many statistical analyses are able to identify strong causal relationships between social categories such as social class, gender and race. These types of knowledge help to explain large causal relationships, and inform us about deep social trends in societies. Even if these types of research mostly explain, reliable interpretation of social situations will tend toward theoretical generalization – which means that the knowledge produced could explain other similar cases even if we could not statistically generalize to a universal conclusion (Pires, 1997).

Sociologists such as Dominique Schnapper (1999) insist that good social research embodies a tension between explanation and interpretation, but one has to know from which pole one is working. The research objectives and the research question will determine if the aim of the research is more likely to produce an explanation – and rely on a linear knowledge production process. Or rather to provide an interpretation – and rely on an iterative production process (Figure 1.2).

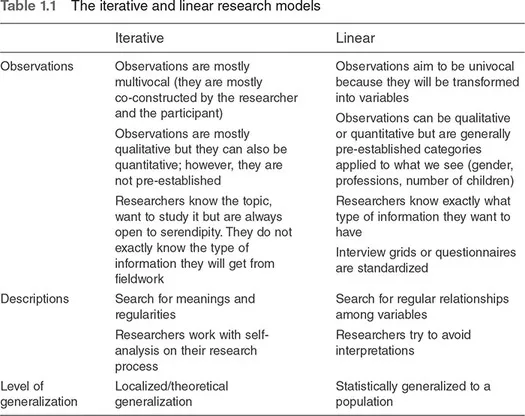

If your aim is to observe a complex phenomenon such as culture, your research design should gravitate toward the interpretation pole and develop an iterative architecture. For example, in each society, cultural boundaries exist to delineate who belongs to ‘us’ (as a ‘community of identification’) and who belongs to ‘them’. In a society highly segregated by race, such as the United States, cultural groups might form around the historical black minority, the historical white majority and other groups (Latino, Asian, Arabic, etc.). Such boundaries can be found through interviews and historical analysis. No universal law can explain the changing cultural boundaries among the groups. In Table 1.1, we present the different aims of observation and description in iterative and linear research models. Here, we refer to observation in a general manner that covers any tool to gather or produce data (we will talk about observation in the strict sense in Chapter 4).

Figure 1.2 Interpreting and explaining

Methodology and Epistemology

As we explained above, all knowledge is based on both explanations and interpretations, but qualitative methods are mostly aiming at producing interpretations of phenomena. What makes a valid body of knowledge is not a simple choice of methods and data. It is the coherence, the rigor and the transparency of a chain of scientific decisions related to the object of study, the problem related to this object, the research questions, the possible answers, the methods of data collection and analysis, and the conclusion. The hard thinking in this decision-making process is the methodology. In other words, methodology is the ‘analysis of the principles or procedures of inquiry in a particular field’ (Merriam-Webster Online, n.d.). In this book, we focus on qualitative methodology defined as an iterative process of knowledge production. Our conception of methodology is not based on a choice of data such as work or numbers, or a choice of methods, for example observation vs. questionnaire. Rather, it derives from a chain of decision-making that will help define your epistemological stance and your research design.

The first thing to do is decide whether a quantitative or qualitative methodology is the most suitable form of inquiry for the type of research problem you have. This decision is related to an epistemological and ontological position. Ontology is a discussion or a reflection ‘about the nature of being or the kinds of things that have existence’ (Merriam-Webster Online, n.d.) and epistemology is ‘the study … of the nature and grounds of knowledge, especially with reference to its limits and validity’ (Merriam-Webster Online, n.d.).

What researchers believe to be reality and what they think is possible to be known is based on beliefs. Guba and Lincoln (2004) explain very well how academic researchers can convince others of the importance of their ontological–epistemological postures, but nobody ‘knows’ if one posture is better than another. The most we can say is that a posture might be more relevant for one research question than another. For example, if researchers want to test the efficiency of a particular vaccine to prevent tuberculosis, they would probably position themselves in a realist ontology. This means that they believe that molecules, atoms and fluids are objectively real; that is, they exist outside the perceptions and beliefs of the researchers. They will also have a positivist epistemology, which means that they believe that the role of science is to understand laws of the natural organization of the reality they define as real. For this, they need to observe data without influencing it and analyse patterns of causality in a hypothetico-deductive way. Considering the experience of cancer patients, one would most likely prefer receiving a drug treatment tested within a positivist epistemology.

However, if we want to understand how patients interpret their recoveries from cancer, we can analyse their experiences of the different types of therapies they underwent such as meditation, yoga, acupuncture, spiritual practices. We could also investigate the support they got from loved ones, the roles they attribute to positive thoughts about their physical health, and so forth. With such questions, we are likely to believe that reality is constructed through our perception and experience of it and we will be interested in the lived experience of treatments and recovery. As cancer patients, we would prefer to be treated by practitioners ...