- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This groundbreaking book takes a humanistic approach to counselling young people, establishing humanistic counselling as an evidence-based psychological intervention.

Chapters cover:

- Therapeutic models for counselling young people

- Assessment and the therapeutic relationship

- Practical skills and strategies for counselling young people

- Ethical and legal issues

- Research and measuring and evaluating outcomes

- Counselling young people in a range of contexts and settings.

Grounded in the BACP's competencies for working with young people, this text is vital reading for those taking a counselling young people course or broader counselling and psychotherapy course, for qualified counsellors working with this client group, and for trainers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Counselling Young People by Rebecca Kirkbride in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I The Development of the Young Person

1 Understanding Young People and their Development

Relevant BACP (2014) competences

- C1. Knowledge of development in young people and of family development and transitions.

- C2. Knowledge and understanding of mental health problems in young people and adults.

- B1. Knowledge of the basic assumptions and principles of humanistic counselling.

Introduction

- Knowledge of child and adolescent development is essential for counselling with young people. It provides a vital structure and background for understanding young people and the issues they present with in the counselling room.

- This chapter begins with a look at some theories of human development beginning with those of Carl Rogers, which form the basis of Humanistic counselling. It goes on to consider Attachment theory along with other perspectives on development in childhood.

- The chapter goes on to consider adolescent development including puberty, socio-emotional, socio-cultural and psychosexual development, and explores how these affect identity formation and separation.

- The chapter ends with an exploration of mental health, including a brief look at diagnosis and understanding of common presentations in young people.

- By the end of this chapter the reader will have basic knowledge of development and mental health as well as information on further resources for these areas.

Due to the breadth of material covered by this chapter, it is divided into three sections: Section 1 – Infant and child development; Section 2 – Adolescent development; Section 3 – Mental health in adolescence.

Suggestions for further reading and other resources are made throughout the text to support readers who would like to look in more depth at the topics covered in the chapter.

Section 1: Infant and child development

Knowledge of the dynamic processes of child development helps create an understanding of the individual which is an essential underpinning of therapeutic work with young people. This knowledge will aid practitioners in understanding their clients and appreciating the origins of their world view. It can be crucial in understanding the developmental needs of young people and the origins of psychological dysfunction, as well as how development might affect the capacity to engage fully in a therapeutic relationship.

The first section of this chapter examines the development of a sense of self. It considers the optimal conditions for this development as well as looking at what happens when those conditions are not provided.

Humanistic theories of growth and development

As explained in the introduction, in line with the BACP (2014) competences framework the central theoretical approach of this manual is humanistic, so it seems appropriate to begin by looking at development from an associated perspective. In 1959, Carl Rogers published a paper outlining his theory of personality development in infancy. Rogers was influenced by two important areas of thinking: those of phenomenology, ‘… which starts from the assumption that human existence can be best understood in terms of how people experience their world’, and that of Humanistic psychology, which held an assumption that, ‘… individuals are propelled forward in the direction of growth or actualization’ (Cooper, 2013a: 119). In Rogers’ (1959) view the infant begins life in an undifferentiated state, i.e. there is no ‘me’ and ‘not me’, no pre-existing core sense of self or of an external, non-subjective reality. As they develop, the infant begins to have ‘self-experiences’, when ‘… a portion of the individual’s experience becomes differentiated and symbolized in an awareness of being, awareness of functioning’ (1959: 223). For Rogers, this marks the beginning of a separate sense of self, or self-concept, which forms the basis of how the infant will experience and make sense of their world. Rogers suggests that next the infant forms a sense of an ‘other’ from whom ‘The infant learns to need love’ (1959: 225), and it is this need for love or positive regard which predominates because of its connection with the need to survive. Without a positive connection to their caregiver, the infant’s survival may be jeopardised and,

Consequently the expression of positive regard by a significant social other can become more compelling than the organismic valuing process, and the individual becomes more adient to the positive regard of such others than toward experiences which are of positive value in actualizing the organism. (Rogers, 1959: 224)

The organismic valuing process referred to here is a concept from humanistic theory that the human organism can be relied upon to lead the individual in the right direction for growth. The need for positive regard can conflict with this process, resulting in the development of ‘conditions of worth’, which arise when an infant is not unconditionally valued by their caregiver. If the child is always wholly ‘prized’ exactly as they are, in other words if they receive unconditional positive regard from the caregiver, then no conditions of worth are arising. If the positive regard of the significant other is viewed as conditional, i.e. the child experiences themselves as prized in some ways and not in others, then a condition of worth will arise, as explained in the following:

Hence, as well as developing an understanding of which self-experiences are worthy of reward by others and those which are not, the infant starts to shape his interactions with others in a manner designed to maximise the positive regard he receives. As a result, he increasingly orientates his attention toward positively regarded self-experiences, such as feelings of happiness and their associated behaviours, attending less to those that invoke less or no positive regard from others. (Gillon, 2007: 31)

Conditions of worth can have a significant impact on the capacity for self-regard as the child begins to prize themselves only in ways in which they have been prized by others (Rogers, 1959). This is crucial in the humanistic theory of psychological wellbeing as it marks the point where the need to obtain positive regard from significant others takes priority over the needs of the organism. This ‘disturbance’ of the valuing process, Rogers argues, ‘… prevents the individual from functioning freely and with maximum effectiveness’ (1959: 210). Humanistic theory views this as where psychological disturbance is most likely to develop and therefore where therapy comes in. For Rogers, the role of the counsellor is to provide a relationship where the client experiences themselves as wholly prized without the imposition of conditions of worth. This enables the reinstating of the organismic valuing process within the individual.

Other theories of growth and development

Erikson and the psychosocial approach

Erik Erikson’s (1950) psychosocial approach to development is outlined in his book Childhood and Society, which is based on Freud’s original psychoanalytic formulations but studies human development from the point of view of different cultures. Erikson suggests in his writing on the human life-cycle and the crises that need to be resolved at each stage of human development that the establishment of a basic sense of trust is vital for the infant, and that it is the relationship with the caregiver which is instrumental in creating this trust. Erikson writes:

Mothers create a sense of trust in their children by that kind of administration which in its quality combines sensitive care of the baby’s individual needs and a firm sense of personal trustworthiness … This forms the basis in the child for a component of the sense of identity which will later combine a sense of being ‘all right,’ of being oneself, and of becoming what other people trust one will become. (1950: 224)

In Erikson’s (1950) model of ‘eight stages of life’, this initial stage lays the ground work for all that succeeds it in developmental terms.

Attachment theory

Rogers’ (1959) view of infant development places the care environment and the relationship with the primary caregiver/s at the centre of the development of the self-structure or self-concept and this, along with genetic predispositions and biological processes, forms the core of contemporary theories of infant development. This is also the approach of Attachment theory, developed by psychologist and psychiatrist John Bowlby during the post-war period of the 1950s and based on the study of infants’ attachment to their caregiver. Attachment theory fits well with Rogers’ view of development and the broadly humanistic theory on which this book is based. From both his earlier ethological studies of animal behaviour, along with work he undertook in 1950 as part of a World Health Organisation (WHO) survey of the mental health of homeless children, Bowlby formulated the idea that, ‘What is believed to be essential for mental health is that the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate and continuous relationship with his mother (or permanent mother-substitute) in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment’ (1969: xi). Bowlby identified human infants, due to their intense vulnerability at birth, as having an innate need to maintain proximity to someone, ‘… conceived as better able to cope with the world’ (1988: 27). Bowlby (1973) suggested that to develop secure attachments, children require caregivers who are psychologically, physically and emotionally available. According to attachment theory, a child’s early experience of their primary caregiver’s ability to respond appropriately to their needs leads to the development of an ‘internal working model’ (IWM) (Bowlby, 1969) akin to Rogers’ (1959) self-concept or self-structure. The IWM is a set of expectations and beliefs which the child develops experientially about self, others and the world, as well as the relationships between them. For example, if a hungry baby who cries is responded to reasonably promptly by their caregiver in a way which is soothing, this begins to form the basis for an IWM developed out of an understanding that behaviours and needs produce positive behaviour on the part of the caregiver. The infant consequently begins to develop a sense that they are loved and worthy of their basic needs being met. If such experiences continue, they will develop trust in an environment which is basically responsive to their needs. Infants not responded to in this way or similarly are likely to develop an IWM of an environment far less naturally responsive and of themselves and their behaviour as responsible for this lack of response. The IWM becomes a fundamental blueprint for the child, determining to an extent how they experience themselves, their relationships, and the world in general as they grow. It contains expectations and beliefs regarding the behaviour of self and others; whether or not the self is loveable and worthy of love and protection, and whether the self is worthy of another’s interest and availability. The term ‘working’ model is significant here, particularly in the context of therapy, as in line with the optimism of the Humanistic approach in general, it indicates that this ‘working’ model can adapt and change in accordance with new experiences.

In line with Rogers’ development of the ‘self-concept’ or ‘self-structure’, the IWM of attachment theory relates to development of the child’s sense of their basic acceptability and worth, as well as their understanding of how reliably others and the world around them will meet their emotional and physical needs. In Rogers’ (1959) theory, the infant may begin to deny and distort its own needs in order to maintain the positive regard of a parent and prevent the perceived threat of withdrawal of love, just as in attachment theory the child adapts their behaviour to maintain an emotional attachment/physical proximity to their caregiver in an attempt to ensure physical and psychological safety. Bowlby (1969) suggests that children instinctively recognise which behaviours seem to please their caregiver and encourage them to maintain proximity, and which trigger rejection, thus threatening the attachment. This adaptation fits with Rogers’ (1959) theory that the infant adapts behaviour in order to secure necessary positive regard from their caregiver.

Classification of attachment patterns

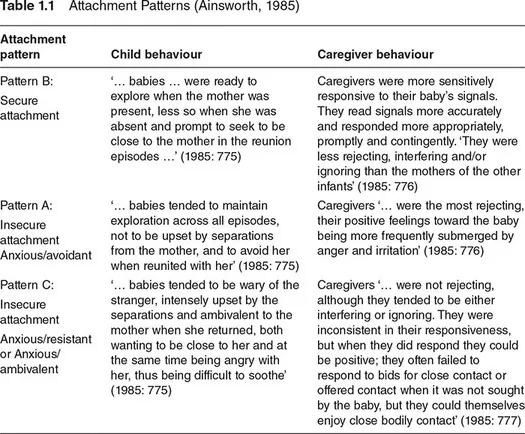

While working alongside Bowlby, psychologist Mary Ainsworth developed the ‘Strange Situation Test’ (Ainsworth et al., 1978) as a way of identifying and categorising children’s attachment patterns. The ‘Strange Situation’ consists of a ‘laboratory situation’ (Ainsworth et al., 1978) which begins with a mother and child aged 12–18 months playing together in a room. A stranger enters and the mother leaves before returning soon after. This experiment was repeated on many different subjects and the observations recorded. The reactions and behaviours of the mother and child throughout the test were monitored and used as the basis for developing classifications of ‘typical’ attachment behaviours. Using the ‘Strange Situation’ on large numbers of mothers and babies in Baltimore, Ainsworth (1985) and her associates arrived at three basic categories of attachment behaviour, as shown in Table 1.1.

A later category of ‘insecure-disorganised’, indicating a confused or traumatised pattern of attachment was arrived at by Main and Solomon (1986), and subsequently included in the patterns of attachment identified by the ‘Strange Situation’.

Relevance of attachment theory for counselling young people

Awareness of attachment patterns and how they originate can be helpful in gaining insight into a client’s world view as well as in understanding their IWMs and how these affect their relationships with self and others.

The following case example demonstrates the potential significance of attachment theory in the case of one individual.

Case Example 1.1: James

James is 15 and has been referred to a voluntary sector young people’s counselling service by a youth worker con...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I The Development of the Young Person

- 1 Understanding Young People and their Development

- Part II Counselling Young People: Theory and Practice

- 2 Therapeutic Models for Counselling Young People

- 3 Assessment with Young People

- 4 The Therapeutic Relationship

- 5 Working with Emotions

- 6 Using Creative and Symbolic Interventions

- 7 Working with Groups

- Part III Counselling Young People: Professional and Practice Issues

- 8 Engaging Young People and their Families

- 9 Evaluation and Use of Measures in Counselling Young People

- 10 Ethical and Legal Issues

- 11 Risk and Safeguarding

- 12 Working with Other Agencies

- 13 Supervision

- 14 Developing Culturally Competent Practice

- Part IV Counselling Young People: Contexts and Settings

- 15 Educational Settings

- 16 Voluntary/Third-sector Settings

- Appendix 1 Map of Competencies

- Appendix 2 Manuals and Texts in the Development of Humanistic Competencies for Counselling Young People (Hill et al., 2014)

- References

- Index