eBook - ePub

Doing a Systematic Review

A Student's Guide

Angela Boland,Gemma Cherry,Rumona Dickson

This is a test

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Doing a Systematic Review

A Student's Guide

Angela Boland,Gemma Cherry,Rumona Dickson

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Written in a friendly, accessible style by an expert team of authors with years of experience in both conducting and supervising systematic reviews, this is the perfect guide to using systematic review methodology in a research project. Itprovides clear answers to all review-related questions, including:

- How do I formulate an appropriate review question?

- What's the best way to manage my review?

- How do I develop my search strategy?

- How do I get started with data extraction?

- How do I assess the quality of a study?

- How can I analyse and synthesize my data?

- How should I write up the discussion and conclusion sections of my dissertation or thesis?

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Doing a Systematic Review an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Doing a Systematic Review by Angela Boland,Gemma Cherry,Rumona Dickson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Carrying Out a Systematic Review as a Master’s Thesis

This chapter will help you to…

- Understand the term ‘systematic review’

- Gain an awareness of the historical context and development of systematic reviewing

- Appreciate the learning experience provided through conducting a systematic review

- Become familiar with the methods involved in carrying out a systematic review

Introduction

In this chapter we introduce you to the concept of systematically reviewing literature. First, we discuss what systematic reviews are and why we think carrying out a systematic review is a great learning experience. Second, we give you an overview of the evolution of systematic review methodology. Third, we introduce the key steps in the systematic review process and signpost where in the book these are discussed. Finally, we highlight how systematic reviews differ from other types of literature review. By the end of the chapter we hope that you will be confident that you have made the right decision to carry out a systematic review and that you are looking forward to starting your research.

What is a systematic review?

A systematic review is a literature review that is designed to locate, appraise and synthesize the best available evidence relating to a specific research question in order to provide informative and evidence-based answers. This information can then be used in a number of ways. For example, in addition to advancing the field and informing future practice or research, the information can be combined with professional judgement to make decisions about how to deliver interventions or to make changes to policy. Systematic reviews are considered the best (‘gold standard’) way to synthesize the findings of several studies investigating the same questions, whether the evidence comes from healthcare, education or another discipline. Systematic reviews follow well-defined and transparent steps and always require the following: definition of the question or problem, identification and critical appraisal of the available evidence, synthesis of the findings and the drawing of relevant conclusions.

A systematic review: a research option for postgraduate students

As a postgraduate student you may be offered the choice of conducting a primary research study (e.g. an observational study) or a secondary research project (e.g. a systematic review) as part of your academic accreditation. There are very good reasons why you are asked to carry out a research project as part of your studies, the most important being that conducting a research project enables you to both understand the research process and gain research skills.

Systematically reviewing the literature has been accepted as a legitimate research methodology since the early 1990s. Many Master’s programmes offer instruction in systematic review methods and encourage students to conduct systematic reviews as part of postgraduate study and assessment. It is widely acknowledged that this approach to research allows students to gain an understanding of different research methods and develop skills in identifying, appraising and synthesizing research findings.

Every Master’s course and every academic institution is different. For you, this means that the presentation of your thesis as part of postgraduate study must be carried out within the accepted guidelines of the department or university where your thesis is due to be submitted. Your thesis must be an independent and self-directed piece of academic work; it should offer detailed and original arguments in the exploration of a specific research question and it should offer clarity as to how the research question has been addressed.

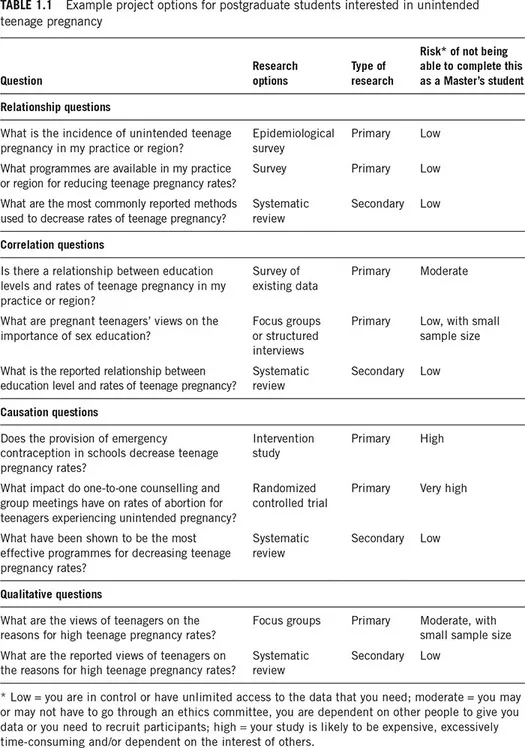

Let’s assume that you are interested in studying issues related to unintended teenage pregnancy. As a researcher, you have a variety of investigational methods open to you. However, the likelihood of being able to pursue these may be impeded by time and resource constraints, as well as by the specific requirements of your academic institution. Table 1.1 illustrates a number of possible project options that may be open to you and the likelihood of you being able to successfully complete your chosen project as part of your postgraduate thesis.

In our experience, students who opt for primary research mainly explore questions relating to current status and/or correlation factors. The main problem with this kind of research is that its generalizability is often hampered by small sample sizes and time constraints. Although conducting a systematic review can be just as time-consuming as undertaking primary research, students who form questions that can be addressed using systematic review methodology have the opportunity to work with a variety of different study designs and populations without necessarily needing to worry about the issues commonly faced by researchers carrying out large-scale primary research. Due to the very nature of a systematic review, students are able to work in the realm of existing research findings while developing critical appraisal and research synthesis skills. A systematic review provides an excellent learning opportunity and allows students to identify and set their own learning objectives.

Good research is rarely carried out on an ad hoc basis. From the outset, you need to be clear about why you are carrying out your systematic review. For example, you may want to evaluate the current state of knowledge or belief about a particular topic of interest, contribute to the development of specific theories or the establishment of a new evidence base and/or make recommendations for future research (or you might just want to carry out your review as quickly and as effortlessly as possible to gain your qualification). However, you need to think about what you want to learn from your postgraduate studies. You might find that balancing your learning objectives with the objectives of your review may be challenging at times; this is most likely to be true if you are reviewing a topic of interest in your professional field (as we suggest you do). Discussing your learning objectives with your supervisor and exploring alternatives with your classmates or colleagues can often help you to clarify these objectives. Box 1.1 outlines some of the advantages and disadvantages of conducting a systematic review as part of a Master’s thesis.

* Low = you are in control or have unlimited access to the data that you need; moderate = you may or may not have to go through an ethics committee, you are dependent on other people to give you data or you need to recruit participants; high = your study is likely to be expensive, excessively time-consuming and/or dependent on the interest of others.

Box 1.1: A systematic review as a Master’s thesis: advantages and disadvantages

Advantages

- You are in control of your learning objectives and your project

- You can focus on a topic that you’re interested in

- You don’t have to gain formal ethical approval for your review before you begin

- You don’t have to recruit participants

- You can gain understanding of a number of different research methodologies

- You can gain insight into the strengths and limitations of published literature

- You can develop your critical appraisal skills

- The research can fit in, and around, your family (or social) life

Disadvantages

- You don’t experience writing and defending an ethics application

- It can be isolating as you are likely to be primarily working on your own

- You don’t face the challenges of recruiting participants

- You may not get a sense of the topic area in terms of lived experience

- You are reliant on the quality and quantity of available published information to address your research question

- You may find the process dull or boring at times

- There are no short cuts and the process is time-consuming

Evolution of the systematic review process

There are some common misconceptions about systematic reviewing. Some students (and supervisors) choose primary research projects over systematic reviews because they worry that systematic reviews aren’t ‘proper research’, or that systematic reviews can only be conducted in the field of health. If you are thinking of conducting a systematic review as part of your Master’s thesis, then we think that it will set your mind at ease to know a little bit about the history and evolution of the systematic review process and the disciplines in which systematic reviews can be carried out.

It might surprise you to know that the systematic review of published evidence is not new. As early as 1753, James Lind brought together data relating to the prevention of scurvy experienced by sailors. He wrote:

As it is no easy matter to root out prejudices … it became requisite to exhibit a full and impartial view of what had hitherto been published on the scurvy … by which the sources of these mistakes may be detected. Indeed, before the subject could be set in a clear and proper light, it was necessary to remove a great deal of rubbish. (Chalmers et al., 2002, p. 14)

From Lind’s farsightedness we move to the 1970s. Two important events took place that laid the foundations for a revolution in the way that evidence could be used to inform practice in healthcare and other areas. In the UK, a tuberculosis specialist named Archie Cochrane had recognized that healthcare resources would always be finite. To maximize health benefits, Cochrane proposed that any form of healthcare used in the UK National Health Service (NHS) must be properly evaluated and shown to be clinically effective before use (Cochrane, 1972). He stressed the importance of using evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to inform the allocation of scarce healthcare resources. At about the same time, in the USA, work by Gene Glass (1976) had led to the development of statistical procedures for combining the results of independent studies. The term ‘meta-analysis’ was formally coined to refer to the statistical combination of data from individual studies to draw practical conclusions about clinical effectiveness. In years to come, outputs of both research communities would combine to form the basic tenets of systematic review methodology.

In 1979, Archie Cochrane lamented:

It is surely a great criticism of our profession that we have not organized a critical summary, by specialty or subspecialty, adapted periodically, of all relevant randomized controlled trials. (Cochrane, 1979, pp. 1–11)

In response, a group of UK clinicians working in perinatal medicine made every effort to identify all RCTs relating to pregnancy and childbirth. They categorized the studies that they found and then synthesized the evidence from these studies. This work led to the development of the Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials (Chalmers et al., 1986). In addition, their groundbreaking work was published in a two-volume book which detailed the systematic and transparent methods that they had used to search for, and report the results of, all relevant studies (Chalmers et al., 1989). This work was instrumental in laying the foundations for significant developments in systematic review methodology, including the establishment of the Cochrane Collaboration in 1992. The Coch...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Table List

- Illustration List

- Sidebar List

- Online Resources

- About the Editors

- About the Contributors

- Foreword

- 10 Step Roadmap to Your Systematic Review

- Preface

- 1 Carrying Out a Systematic Review as a Master’s Thesis

- 2 Planning and Managing My Review

- 3 Defining My Review Question and Identifying Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- 4 Developing My Search Strategy

- 5 Applying Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- 6 Data Extraction: Where Do I Begin?

- 7 Quality Assessment: Where Do I Begin?

- 8 Understanding and Synthesizing Numerical Data from Intervention Studies

- 9 Writing My Discussion and Conclusions

- 10 Disseminating My Review

- 11 Reviewing Qualitative Evidence

- 12 Reviewing Economic Evaluations

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- References

- Index