- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Social Media

About this book

Exploring questions of both exploitation and empowerment, Understanding Social Media provides a critical conceptual toolbox for navigating the evolution and practices of social media.

Taking an interdisciplinary and intercultural approach, it explores the key themes and concepts, going beyond specific platforms to show you how to place social media more critically within the changing media landscape.

Updated throughout, the Second Edition of this bestselling text includes new and expanded discussions of:

- Qualitative and quantitative approaches to researching social media

- Datafication and algorithmic cultures

- Surveillance, privacy and intimacy

- The rise of apps and platforms, and how they shape our experiences

- Sharing economies and social media publics

- The increasing importance of visual economies

- AR, VR and social media play

- Death and digital legacy

Tying theory to the real world with a range of contemporary case studies throughout, it is essential reading for students and researchers of social media, digital media, digital culture, and the creative and cultural industries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding Social Media by Larissa Hjorth,Sam Hinton,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Writing a book about social media is about as hard as it can get. Once the platform practices have been documented and analysed, they have already passed their hashtagged used-by date. #solastyear. Doing a second edition of the Understanding Social Media book isn’t just a process of providing an updated preface. Rather, it requires a complete rewriting in which we attend to all the diversities of complex social media practices, cultures and industries that have rapidly emerged. Like the previous edition, this book seeks to provide an overview of some of the key issues relating to studying social media through key paradoxes – concepts such as invisibility/visibility, empowerment/exploitation, autonomy/algorithmic platformativity, user-generated/platform corporate personalization, power and powerlessness, tactics and strategies.

Since the first edition, a key phenomenon has emerged – the role of the mobile as synonymous with social media and also, interrelatedly, the rise of the visual. Core to these practices are the integral role sharing and datafication has played in recalibrating what is social media today. As noted by scholars such as Mark Deuze (2012) and José van Dijck (2007) while media has always been social, what it means to conceptualize and practise the social in contemporary automated and datafied culture is changing. The social is a contested and dynamic space – epitomized by social media.

The rise of mobile media, visuality and sharing has a long history in the inception of camera phones, in which the role of sharing forms part of its logic (Frohlich et al., 2002; Kindberg et al., 2005; Van House et al., 2005; Koskinen, 2007). As mentioned above, the logic of sharing is the default function for much of social media (van Dijck, 2007). For van Dijck in The Culture of Connectivity (2013), sharing has become the ‘social verb’. A doing word. An embodied practice of contemporary digital media lives. Expanding on this idea further, Nicholas A. John argues in Age of Sharing (2016) that sharing is central to how we live our lives today – it is not only what we do online but also a model of economy and therapy.

And yet the rise of the social dimensions of sharing social media – in the form of memes, Instagrams, hashtags, to name but a few – has a core paradox in that it partakes in the rhythms and logic of platforms and corporate algorithms and datafication. Here, at the core of this ‘datafication’ paradox, users willingly hand over their data and other forms of social, creative and emotional labour to platforms (corporations) which then monetize their preferences in order to sell back to the users (van Dijck, 2017).

According to van Djick and Poell (2013), social media logic has four grounding principles: programmability, popularity, connectivity and datafication. These principles and strategies are pervasive across all areas of public life. Or what Zizi Papacharissi (2014) calls ‘affective publics’ – the digital storytelling processes of public engagement that create affect and emotions in ways that fully erode boundaries between political, public and intimate lives. For Papailias (2016), contemporary mobile social media elicits certain types of affect that blur boundaries between witness and mourner. Social media is now often framed as digital intimate publics (Hjorth & Arnold, 2013; Dobson et al., 2018), as a way to make sense of the paradoxes that see old divisions challenged – between self and society, public and private, digital and offline. This phenomenon is a consequence of the role mobile media plays in providing a particular embodied and intimate context for social media (Hinton & Hjorth, 2013; Hjorth & Arnold, 2013; Goggin, 2014; Carr & Hayes, 2015; Fuchs, 2017).

Figure 1.1 #catsoninstagram continues to dominate as an extension of Ethan Zuckerman’s activist theory of cute cats

In this Introduction we will outline some of the key paradoxes explored in this book. We will begin with contextualizing the paradoxes around social media, and then outline some of the multiple and contested definitions. We will then outline the role of each chapter in the logic of this book. From the outset, we should make it clear that this book does not intend to be an exhaustive guide, but rather an examination of key arguments. For a more holistic guide, please refer to The Sage Social Media Handbook (Burgess et al., 2018).

Instead, we wish to provide critical analyses and insight into the various contested histories, methods, economies, cultures and practices to give readers a conceptual overview. We draw on fieldwork studies in various locations, such as China and Japan, to provide English speakers with a broader context for the ways in which global social media is playing out in various ways at the level of the local.

Key debates

At the beginning of 2018, two events represented one of the core paradoxes of social media in terms of sharing and disclosure, visibility and invisibility, empowerment and exploitation. The first was the fact that the top new entry in the Macquarie Dictionary for 2017 was ‘milkshake duck,’ the term used to describe the volatile rhythms of social media publics whereby someone can become famous on social media only to then have their reputation ruined by those same social media publics.

Figure 1.2 ‘Snowflake Boy’ or ‘Ice Boy’

At the same time in January 2018, a story in rural China went viral, the story of an eight-year-old boy (Wang Fuman) who walked four kilometres to school in freezing snow and arrived with head, eyebrows and eyelashes full of icicles. Wang was dubbed ‘Snowflake Boy’ or ‘Ice Boy’. The primary school teacher took a picture of Wang and shared it on WeChat, China’s most popular social media platform. The image and story took on political dimensions, with some arguing that Wang represented the tenacity of the rural people, while others argued that the rural poor people like Wang were being forgotten in the narratives of Chinese modernity and its focus on urban megacities. During an interview with Wang on national TV he announced that he wasn’t sure his fame was a good thing, despite receiving reports of US$200 million in donations globally.

What these two social media phenomena highlight is the paradoxical nature of social media to create what Papacharissi (2014) calls ‘affective publics’ – that is, an entanglement between visibility/invisibility and agency/disempowerment that are subject to global storytelling, contestations and whimsy. As social media becomes indivisible from mobile media, we see the acceleration of users’ ability to take and share images and stories. Events and activities become measured through their Instagrammable quality as part of broader tensions around user creativity and datafication, in terms of what Thomas LaMarre calls ‘platformativity’ (2017: 24). As LaMarre further explains: ‘In platformativity, the platforms and infrastructures play an active role, or more precisely, an intra-active role, as they iterate, over and again’ (2017: 25). What becomes apparent in the accelerated cycles of social media discourses is the amplification of inequality within digital intimate publics.

For example, take the successful augmented reality (AR) game Pokémon GO, which created a phenomenon across much of the world in 2016. It was so successful, it even surpassed porn in terms of downloads. And in its collective social orchestration of playful performativity around urban cartography, Pokémon GO harnessed core debates around datafied (or gamified) worlds, from a variety of perspectives including wellbeing (the fact that games make people exercise to achieve goals which in turn can impact positively upon mental wellbeing issues) and the social dimensions of games, to the more dark debates around safely, surveillance and risk (Hjorth & Richardson, 2017).

As platforms such as Facebook throw resources and capabilities around the mainstreaming of AR and virtual reality (VR), we see paradoxes persist around agency and disempowerment, especially as digital literacies continue to remain unequal across generational, socio-economic and cultural divides. The rise of social VR, spearheaded by companies such as Facebook’s Oculus, presents some challenges and opportunities in this space. Moreover, as bots and artificial intelligence (AI) start to inhabit social media to the point that ‘followers’ are now viewed as fake news, the debates around user agency and datafication become magnified. In these Big Data narratives, alternative human-centred (and ‘more-than-human’) social digital methods emerge around ethnography and critical making.1

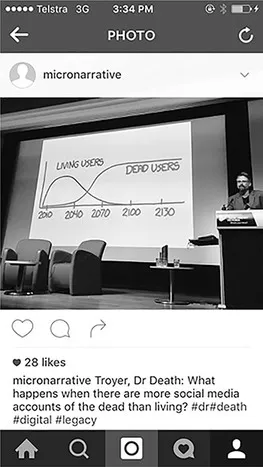

As a social medium, understanding social media requires attending to some core fundamental issues to being human. While much of social media has focused on life (Deuze, 2012), and especially birth – or even before birth, as can be seen in Tama Leaver’s intimate surveillance work (2013) – the significance of death becomes increasingly pertinent. For example, estimates have Facebook having more dead users than live ones in five years’ time. What does it mean to have death and the afterlife constantly streaming in our lives? And what is the politics of Facebook owning our loved one’s accounts? Emerging fields of compassion studies (Brubaker et al., 2014) are attempting to attend to this growing area of complex ethical issues that in turn impact upon how we practise and experience social media now and in the future (as we discuss in Chapter 12).

Figure 1.3 Dr John Troyer, director for the Centre for Death & Society (UK), on the rise of dead users

To understand the life and death of, and in, social media we need to survey the diversity of contesting and dynamic definitions. Scholars such as van Djick and Graeme Meikle identify the role of sharing and visibility as central to the logic of social media. For Meikle (2016), the tension between sharing, visibility and privacy constantly plays out through social media as today’s dominant form of mass communication. Indeed, tensions and paradoxes around visibility and agency, surveillance alongside privacy, invisibility and intimacy have attracted much attention from a variety of social media scholars (Fuchs, 2014, 2017; Meikle, 2016; van Dijck, 2017; Marwick & boyd, 2018).

While it is uncontested that we live in the ‘age of social media’ (Lamberton & Stephen, 2016), and social media services such as Facebook, WhatsApp, WeChat, LINE and YouTube have amassed billions of users, definitions remain multiple and disputed. Beyond definitions understood broadly as ‘digital technologies emphasizing user-generated content or interaction’ (Carr & Hayes, 2015: 47; see also Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010), social media definitions are as varied as the platforms themselves. Many of the more encompassing definitions of social media are criticized for their lack of delineation between social media and ‘traditional’ new media (email, text-messaging, etc.) and/or for ‘obscuring the ways the [social media] technology may influence behaviors’ (Treem & Leonardi, 2013: 145) and ‘missing the unique technological and social affordances that distinguish social media’ from non-social media (Carr & Hayes, 2015: 48).

Narrower classifications of social media are equally problematic, often referencing specific social media services (i.e. Facebook, Twitter) in their definition or conflating them with social media subcategories – social networking sites in particular – resulting in definitions of social media with limited scope and poor interdisciplinary utility (Treem & Leonardi, 2013; Carr & Hayes, 2015).

However, one definition of social media that traverses the broad and narrow perspectives is given by Caleb Carr and Rebecca Hayes (2015) in their article ‘Social Media: Defining, Developing, and Divining’. Building on a review of a decade of social media definitions across various disciplines alongside a keen analysis of shifts in social media platforms and user behaviours, Carr and Hayes define social media as ‘[i]nternet-based, disentrained, and persistent channels of masspersonal communication facilitating perceptions of interactions among users, deriving value primarily from user-generated content’ (2015: 49) or, in more ‘accessible’ terms:

Social media are Internet-based channels that allow users to opportunistically interact and selectively self-present, either in real-time or asynchronously, with both broad and narrow audiences who derive value from user-generated content and the perception of interaction with others. (2015: 50)

Carr and Hayes’ definition serves two primary functions. The first is to clearly distinguish ‘a social medium from a medium that facilitates socialness’ (2015: 49) and in turn to isolate the exclusive properties of social media that separate them from other communicative new media forms. The second function of Carr and Hayes’ definition is to identify a ‘set of traits and characteristics’ that are common to all social media platforms – extant and emergent – and to avoid definitions of social media that are reliant on specific platforms and subcategories. In doing so, they further extend the development of social media theory across wider, interdisciplinary settings (2015: 49).

Chapter summaries

In this section we summarize the chapters and book structure, and outline the key paradoxes underscoring the book’s discussion of social media. We argue that the coalescence of social with the media, while media has always been social (Deuze, 2012; van Dijck 2013), represents key challenges for how we define the social and its entanglement with the digital. With the convergence of social media with mobile media, the intimate attunements of mobile media as an embodied form of social proprioception (Farman, 2011) in the form of mobile intimacy (Hjorth & Lim, 2012) takes on magnified proportions.

Phenomena such as the rise of applification, especially in the form of camera phones and self-tracking Quantified Self (QS) features, see three key characteristics of contemporary social media sharing: visuality, platformativity (user creativity versus corporate algorithmic logic) and datafication. Moments, as we see in the case of museums and galleries, are being measured in terms of Instagrammable qualities. The key paradoxes of the current chapter include visibility and invisibility; agency and disempowerment (milkshake duck); sharing and non-disclosure; user creativity versus corporatization; autonomy versus platformativity.

The role of visibility and invisibility in social media is a highly gendered preoccupation (Brighenti, 2010; Hendry, 2017). For Brighenti ‘visibility is a social dimension in which thresholds between different social forces are introduced’ (2010: 5). Van Dijck (2013) talks about ‘sharing’ as the verb for socializing in social media. Debates around visibility and invisibility cannot be separat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- Part 1 Histories And Contexts

- 2 Approaches to Social Media

- 3 Histories of Social Media

- Part 2 Economies And Applification

- 4 Datafication & Algorithmic Cultures

- 5 Mobile Applification

- 6 Geolocation & Social Media

- Part 3 Cultures

- 7 Social Media Visualities

- 8 Mobile Media Art: The Art of the Social

- 9 Museums & New Visualities

- Part 4 Practices

- 10 Paralinguistics

- 11 Social Media & Mixed Reality

- 12 Social Media & Death

- 13 Conclusion

- References

- Index