![]()

Section 1 Defining Criminological and Forensic Psychology

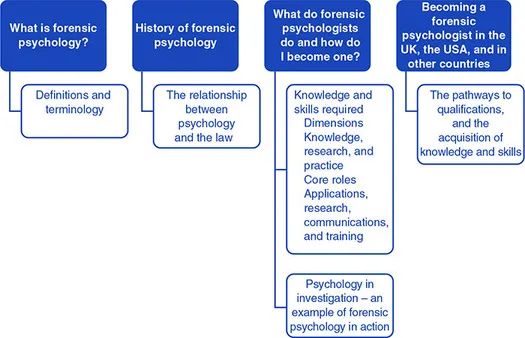

This section introduces the concepts fundamental to the psychological study of crime. In terms of defining what forensic psychology is, and its relationship with other psychological approaches to crime, Chapter 1 defines the topics to be examined and outlines what forensic psychologists do, and how that is different from the wider psychological perspectives. Chapter 2 examines how research in psychology and the methods of psychological research can be applied to the study of crime. This chapter relates to the research dimension and core role of research, but also core role of applications because it introduces the elements of research and research practice that are important to forensic psychologists. The need to remain informed about developments in the discipline is a fundamental component of professional practice, as well as contributing to research where possible.

![]()

1 Defining Forensic Psychology

Imagine a granite-faced Scotsman, moodily smoking a cigarette, and staring at a murder suspect with ill-disguised distaste. Or a group of impossibly attractive people flying across country in a jet to solve crimes for other police officers. Or a beautiful young woman who can ‘see’ crime scenes through the eyes of others, usually the perpetrator.

Familiar images? Yes, probably, if you have ever watched any TV programme about forensic or criminal psychologists. Truthful images? Well, no, they are made for dramatic effect and contain only a germ of the truth. So, what does it mean to be a psychologist who deals with crime and what is the truth behind the drama and mayhem portrayed on the TV screen?

What is Forensic Psychology?

The term ‘psychology’ was probably first used by Goclenius, a German philosopher, who wrote about various philosophical positions in 1590 in a book called Problematum Logicorum (Dyck, 2009). The word itself comes from the Greek for ‘soul’ or ‘spirit’ (psyche), so ‘psychology’ was originally termed to describe the study of the soul. As we know, whatever the focus of psychology, the ‘soul’ in some people can very dark indeed. It is that darkness that forms the core of forensic or criminological psychology. In modern use, psychology is a science, a special kind of science, that aims to define, study, and understand the workings of the mind by interpreting behaviour in order to predict what people will do.

However, in modern use, ‘psychology’ is, for many people, a science, albeit a special kind of science, that fascinates students, practitioners, and lay people alike. There are various specialisms within the broad field of psychology, and forensic psychology is one of them, and, if the use of it in drama is anything to go by, one of the more fascinating. The word ‘forensic’ is from the Latin term forensis, meaning ‘of the forum’, because Ancient Rome’s forum was where the law courts were held. We now refer to forensic sciences as the application of scientific principles to the adversarial law process.

Where does such terminology leave forensic psychology? Forensic psychology is strictly the term describing the application of psychology to the legal process, and it has a long, long history. It holds a special relationship to other fields of study, such as criminology, law, and medicine, and the ways in which those relationships influence research and practice culminate in a growing understanding of crime.

History of the Use of Psychology in the Study, Investigation, and Punishment of Crime

The relationship between psychology and the legal system is an ancient one. The Greek philosopher Aristotle stated, in his books Nicomachean Ethics, written around 340 bc, that a person should only be considered morally responsible for a criminal act if he has knowledge of the circumstances and acted without external compulsion. Hence a crime is only punishable if the character of the offender is under his own control (Pakaluk, 2005). A seemingly enlightened view for more than 23 centuries ago, such philosophical positions took many years to be incorporated into any form of legal system, and this history is littered with what to modern eyes appears to be injustice. The concept of insanity as mitigation in English law was not considered until the fourteenth century, and then only in cases of ‘absolute madness’ (Allnutt et al., 2007). This is the point at which common law courts were directed that defendants must be capable of assisting in their own defence. If they were deemed incompetent due to insanity or mental defect, then the court would not proceed with the prosecution (Otto, 2006). However, there is little record of what happened to the defendant after that decision was made.

According to Spielvogel (2007), it is during the Age of Enlightenment that we find the first acceptance of the status of expert witness testimony in court. In 1723, ‘The Wild Beast Test’ became the standard exemption from punishment, meaning that a man ‘that is totally deprived of his understanding and memory, and doth not know what he is doing, no more than an infant, than a brute, or a wild beast, such a one is never the object of punishment’ (Taylor, 1997: 103). This was followed by the development of systematic criminal investigation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This is also the time, perhaps coincidently, when experimental psychology was beginning to emerge as a scientific discipline and clinical psychology became established as a profession in its own right.

Forensic psychology, as a specialism within clinical psychology, or as a distinct discipline, grew out of the need for psychological evidence to be used in law and the legal process. Forensic psychology is strictly seen to be concerned with psychological aspects of legal processes, but the term can also be applied to investigative and criminological psychology, in which theory is applied to criminal investigation, psychological explanations of crime, and the treatment of criminals. The first recorded event of expert psychological testimony being used in court is not until 1896, when Albert von Schrenk-Notzing argued against the conviction of a man accused of murder. He testified that, due to the huge pre-trial publicity the case had attracted, the witnesses would be unable to distinguish between what they actually witnessed and what was reported in the newspapers. It is also in the nineteenth century that psychology and the study of the mental state was first examined rigorously, and Hugo Munsterberg published the first essays in forensic psychology in 1908. In the USA, perhaps the first systematic study of legal testimony was carried out by Cattell in 1895, starting a process that leads us to today’s knowledge about witnesses and their memory (Brown and Campbell, 2010). Therefore, although forensic psychology can claim to be a discipline with hundreds of years of history, in reality, as a recognised professional practice, it is little over 100 years old. This means it is a mere child in comparison to the use of medicine in law; the first forensic medicine textbook was written in China in 1247 by a man regarded as the father of forensic science, Song Ci (Peng and Pounder, 1998). Even this is predated by fifth-century European laws specifying the employment of physicians to determine cause of death (Wecht, 2005).

However well established forensic psychology might be, it is a misunderstood practice, mainly due to the romanticising of the discipline in the media, and the somewhat prurient interest of the public in anything to do with crime, criminals, and detection.

What Do Forensic Psychologists Do and How Do I Become One?

A forensic psychologist can be involved in a variety of activities. Professional bodies for psychology, such as the British Psychological Society (BPS, www.bps.org.uk), the American Psychological Association (APA, www.apa.org), and the Australian Psychological Society (www.psychology.org.au), describe these tasks as being central to legal processes, and covering aspects from crime scenes to testimony in court. As forensic psychology is the interface between matters legal and matters psychological, it follows that forensic psychologists are both subject to the law and have influence on it. In fact, forensic psychology is now a term used to represent any application of psychology to any aspect of the legal and criminal process, although when psychology is used in the detection and investigation of crime, it is now quite often referred to as ‘investigative psychology’ (see Canter and Youngs, 2003). If an academic researcher is investigating causes of crime in order to understand criminality or how to prevent crime, rather than the detection and prosecution of criminals, this is more likely to be referred to as ‘criminological or criminal psychology’. A further distinction is the recognition of a subdiscipline by the relevant professional body. The BPS recognises forensic psychology as a distinct area of study in its own right and accredits training courses leading to the qualification. If someone wishes to be known as a forensic psychologist, he or she must also register with the Health and Care Professionals Council (HCPC) as this is now a protected title. A psychologist can only apply for registration if they have completed the training and supervised practice in that area (see ‘Becoming a forensic psychologist in the UK, the USA, and in other countries’ below). Criminological psychology (or more simply criminal psychology) does not require such registration, although many academics/researchers in criminological psychology have undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in psychology. Research requires no registration with a professional body or council, but will form the body of knowledge from which forensic psychology draws its currency and authority to claim it is based on valid and verifiable findings. The activities and actions of a forensic psychologist are therefore bound up with the research and evaluation that criminological psychology provides, but criminological psychology is not restricted to the practice of forensic psychology.

Activities in Forensic Psychology

- Statistical analysis of crime trends

- Statistical analysis for offender profiling

- Crime scene analysis

- Providing expert testimony in court

- Assessing suspects for fitness to be charged, questioned, or tried

- Hostage negotiation

- Offender treatment programmes

- Academic/practice research programmes

Psychology in Investigation

Once a crime has been committed, psychology can play some interesting roles in the investigation process, including crime scene analysis and profiling. These roles are perhaps the areas that have been depicted most in fiction, but despite this, or maybe because of it, are particularly misunderstood functions of forensic psychology. Aamodt (2008) describes elements in the field that are particularly susceptible to misinterpretation including assumptions about profiling serial killers, high levels of police officer suicides, or fluctuation in crime rates. He suggests that this is due not only to media representation of these issues, but also the tendency to ignore primary sources of material that might conflict with beliefs of this nature. In particular, profiling involves the understanding of human behaviour and psychopathology, and requires examination of aspects of a crime scene in order to build a picture of an offender, therefore it requires a good deal of study and expertise. Such profiles can be very accurate, and hence can be used to guide investigatory processes. The problem is that, if those using them are susceptible to false beliefs about profiling, they can be viewed as over-accurate; investigators sometimes use the profile as if it were physical evidence, rather than a means to narrow searches and eliminate suspects.

In 1992, Rachel Nickell was sexually assaulted and stabbed to death on Wimbledon Common, the only witness being her 2-year-old son. As Leppard (2007) reports, this was a high-profile case, possibly due to the victim’s youth and attractiveness, or the horror attached to the idea of a young child witnessing such a terrible attack. There were few suspects, but the investigation alighted on Colin Stagg, a loner who appeared to have violent sexual fantasies and who frequented the Common. At the same time, the police had asked a well-known psychologist, Dr Paul Britten, to compile a profile, based on sexually deviant aspects of the crime. The profile was accepted as an accurate assessment not of the type of person who would have committed the crime, but of Stagg’s personality and behaviour (Herndon, 2007). The police set up what became known as a ‘honey trap’ – an undercover female police officer attempted to trap Stagg into revealing he had killed Rachel Nickell. He did reveal some sexual fantasies, but nothing in his conversations with the police officer ever suggested he killed the woman. Nevertheless, the police were convinced that they had their man and proceeded to charge and prosecute Stagg for the murder. Their major evidence comprised the profile and communications with the policewoman. As the trial approached, in 1994, the presiding judge, Mr Justice Ognall, decided that the material demonstrated manipulation of the accused in a reprehensible manner, an attempt to incriminate by police deception (Gregory, 2007). In other words, the police set out to find evidence to cause Stagg to look guilty based on the profile, and the manner in which they did this constituted entrapment. The judge ruled that the evidence was inadmissible under section 78 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984. The prosecution case collapsed, and Stagg was formally acquitted. Robert Napper, a serial rapist who had attacked and killed another woman and her daughter since Rachel’s death, was charged in 2007 with the murder of Rachel (Leppard, 2007), and on 18 December 2008, he pleaded guilty to Rachel’s manslaughter on the grounds of diminished responsibility.

Profiling took a severe blow, its theoretical and empirical foundations shaken. The unwise way in which the profile was used, the advice of the profiler being followed slavishly, was subjected to harsh scrutiny and criticism by the media. Britton was subjected to a disciplinary hearing by the British Psychological Society (BPS) on charges of professional misconduct. The charges were subsequently dropped, but he was soundly criticised by psychologists such as David Canter, the pioneer of statistical profiling, for not advising the police that the profile was illustrative and not made to identify an individual. Canter also pointed out aspects of the crime which were missing from the profile, and which might have led the investigation away from Stagg, such as the brutality of the attack in front of a child (Cohen, 2000). Napper went on to kill other women and the 4-year-old daughter of one of his vict...