Introduction

You may approach your research in many different ways, using different data-collection methods and analysis techniques. Although classic grounded theory (GT: see Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Glaser, 1978; Holton & Walsh, 2017) welcomes many different data-collection methods, it provides a precise and comprehensive set of systematic procedures to sample and analyze data. In this chapter, after briefly explaining the different ways through which you may approach your research (deductive, inductive and/or abductive), we answer what we consider a fundamental question related to the GT approach (whether it is strictly limited to qualitative research or if it welcomes any type of data, qualitative and/or quantitative), and we highlight its different streams (classic or Glaserian, Straussian, etc.), to allow you to decide for yourself if GT is suited to your research purpose.

To avoid possible misunderstandings, in this introduction we define some words commonly used by many authors with different meanings. We do not claim that these definitions are valid across all domains for all authors, however, they will apply throughout the chapters that follow. Therefore data-collection methods for example are the media through which data are collected in a research project, e.g. interviews, observation, filming or surveys. The analysis techniques are the instruments used in a research project to help analyze and make sense of the collected data, e.g. text analysis, cluster analysis or structural equation modeling. The methodology is the specific combination of data-collection methods and analysis techniques used in a research project. The framework is the general set of guidelines proposed by some authors that you might choose to follow in a given project, e.g. those of Baskerville and Pries-Heje (1999) for action research, or those of Eisenhardt (1989) for case-study research. The paradigm is the worldview, which includes the philosophical assumptions that traditionally impact your ontological (i.e. what you consider does exist), epistemological (i.e. what you consider knowledge is), methodological (i.e. what set of data-collection methods/analysis techniques you consider may be used to obtain knowledge), and axiological (i.e. what you consider is valuable) beliefs/choices.

Different ways to approach research

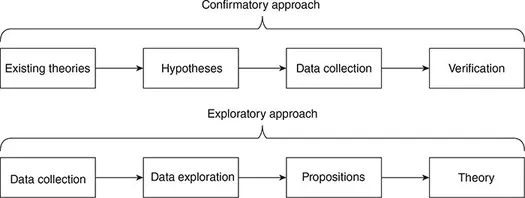

When you conduct research in a given domain, broadly speaking, you can go about it in two general ways: a confirmatory hypothetico-deductive or exploratory inductive approach (see Figure 1.1).

You can start from one existing general theory that has been previously verified by other researchers as valid and test its hypotheses in a specific area and with a population that interests you. You can also use existing theories and knowledge to lay down some new hypotheses. You then collect data to verify these hypotheses. For example, you could use quantitative data through a survey with a statistically valid sample of the targeted population. This approach is confirmatory hypothetico-deductive, i.e. you confirm (or reject) hypotheses that you extracted or developed, based on existing theories discovered by other researchers and published in the existing literature. In other words, you deduce a theory from existing ones.

Alternatively, you can start with some qualitative and/or quantitative data, to investigate your domain of interest and explore the collected data to lay down some propositions (a statement that deals with new concepts or some elements, for which no measure has yet been developed) or hypotheses (a statement that deals with elements that may be measured, and that may be tested) towards perhaps what could be a totally new theory, which might be subsequently verified. This last approach is an exploratory inductive approach that is based on the exploration of your data, from which you propose a theory. You start with data collected from a specific population in a specific context and you infer a theory that may be more or less generalizable. In other words, you start with data and propose a theory that fits your data. This second option does not mean that you will ignore existing theories. It only means that you will investigate the literature and existing theories once your own theory has started to emerge. In some instances, you might eventually find new concepts or theories, enrich existing theories with new properties or dimensions, or you may find that you have confirmed an existing theory, which is also an interesting result in itself.

These two different research approaches are summarized in Figure 1.1. Examples of the two approaches to investigate the same research domain are provided in Box 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Different research approaches

Box 1.1 Examples of the two different basic approaches to conduct research

John and Mary have decided to do their respective master’s projects in the domain of acceptance and use of new information technologies (IT); more particularly, they wish to investigate the different ways through which people approach and use new information technologies.

John chooses to use existing theories and adopt a confirmatory hypothetico-deductive approach. First, he investigates the literature and identifies the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) as the model that is most often applied and validated in relation to IT acceptance and usage. The TAM tells him that the easier to use and the more useful a new IT is perceived, the more people will be intent on using it. John then lays down the hypothesis that if new virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR) applications are perceived as useful and easy to use, people will be intent on using them. He collects quantitative data through a survey and tests if his hypothesis is verified in a statistically representative sample of his targeted population.

Mary wishes to adopt an exploratory approach to investigate what motivates people to use some new IT, without considering the TAM: she does not know anything about this model. She samples a population of very different people in terms of age, position, education, etc., with very different degrees of exposure to new IT. She does not lay down any hypothesis and remains in an exploratory inductive stance. She discovers that the more exposed and acculturated people are to technologies, the more they will be inclined to use any new virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR) application proposed to them, irrelevant of their ease of use or usefulness. This result tends to contradict or complement TAM, a model that she will discover when she investigates the literature after she has laid down her own theoretical propositions.

We cannot talk about induction and deduction without at least mentioning abduction as a logic that complements induction and deduction towards eliminating or clarifying doubtful and/or unclear ideas: ‘Deduction proves that something must be’, ‘induction shows that something actually is operative’, while abduction suggests that ‘something may be’ (Peirce, 1965: §171) and is most probable. Box 1.2 below illustrates the logic of abduction as conceptualized by Peirce (you may find other conceptualizations of abduction, which are beyond the present book).

Box 1.2 Example of the logic of abduction

In the example of Mary’s research above, Mary found that overall, in her sampled population, many of the younger people who were immersed in IT from a very young age, tended to be more IT acculturated and at ease with technologies than older people. She used qualitative data and her sample was not statistically valid. Hence, she could not deduct that age was an explanatory variable to IT acculturation. Using abductive logic, she inferred simply that age was a significant variable to take into account in her research. She decided to make sure to keep track of this demographical element for all participants as it might help explain IT acculturation.

This book is about an approach, a research process that helps to conduct research using the second option (exploratory inductive approach). We explore data to propose theories that may confirm, enrich or contradict existing ones. However, it has to be mentioned that even though doing GT is an overall exploratory inductive approach, it does use deductive and abductive reasoning in its research process (Glaser, 1978; Walsh et al., 2015b). For instance, and as highlighted by Glaser (1978), the theoretical sampling that we will see in detail in Chapter 3 is deductive: you deduce where to sample next, based on an inducted hypothesis.

The GT research process allows the systematic generation of theory from data that have themselves been systematically obtained (Glaser, 1978). We must highlight that the term ‘grounded theory’ may itself lead you to some misunderstanding because it describes at the same time both the research process and the end result, i.e. a new theory that is empirically grounded in data. In the present book, and in order to clarify this issue, we use the abbreviation ‘GT’ when we mean the research process, the GT methodology; and we use the full term ‘grounded theory’ when we mean the end result of a GT study, i.e. a theory grounded in data. We must also highlight that classic GT may be considered at the same time as a data-collection method, an analysis technique, a methodology, a framework, a paradigm or an approach (Walsh et al., 2015a). In this book, we will use in the different chapters the term that best applies depending on the issue that is being debated.

In GT, the main concern is the prime motivator, interest or problem investigated. The result of GT, a grounded theory, is a conceptualized explanation of how the main concern is managed or resolved by those involved, i.e. the population investigated. For example, Holton (2007) investigates knowledge workers (professionals – doctors, nurses, professors, systems analysts, managers, consultants, etc. working in knowledge-based organizations) whose main concern emerges as being the dehumanizing impact of persistent and unpredictable change in their workplaces. In the examples provided in Box 1.1, the main concern that is being investigated could be ‘understanding what makes people intent on using a new IT.’

A grounded theory is more than a description of research findings; it offers a theoretical explanation that is conceptually abstract and that is found to occur in diverse groups with a common concern (Glaser, 2003). GT focuses on participants’ perspectives and provides them with opportunities to articulate their thoughts about issues they consider important, allowing them to reflect on these issues of concern. GT enables you to get close to the phenomenon under study, and participants’ main concern, through extensive and iterative data collection and analysis, responding to latent patterns of social behavior as they emerge from the data and, through their conceptualization, serving as a guide for successive data collection and analyses. Conceptualizing data – simply put, ‘naming a pattern’ found as recurring in data – grounded in reality provides a powerful means both for understanding the world ‘out there’ and for developing action strategies that will allow some measure of control over it (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Concepts are abstract or generic ideas generalized from particular instances (Merriam-Webster’s dictionary) within the data. Conceptualization is not an act of interpretation, it is an act of abstraction. This abstraction to a conceptual level explains theoretically rather than describes behavior that occurs in many diverse groups with a same concern (Glaser, 2003). GT’s particular value is in this ability to provide a conceptual overview of the phenomenon under study – what is actually going on. As a research strategy, GT is particularly appropriate for studies of emerging organizational phenomena and complex environments. As the process of conceptualization is a rather abstract process, we provide two concrete illustrations of it in Box 1.3 below.

Box 1.3 Two illustrations of conceptualization

In these two illustrations, we show how a concept emerges from different accounts.

Letitia is exploring the subject of quality in higher education as perceived by the various stakeholders. She has interviewed students and professors in several universities, and has also used texts provided by accreditation bodies as sources of data. From the verbatims and text extracts like those below, she conceptualized the category ‘Wanting reputation to be tangible’ as being a significant expectation in relation to quality in higher education. Source: Loyola de Oliveira, work in progress, PhD Dissertation.

‘The quality of the learning experience goes beyond the courses themselves that are being taught. You have to have adequate infrastructure: campus, classrooms, technology, etc.’ (Professor)

‘Sometimes, there are not enough seats in the classrooms. If we don’t fi...