![]()

Part 1 Introduction

In this part of the book, we want to discuss what we mean by challenging behaviour, why it occurs and who’s to blame. In doing this, we challenge some of the commonly held assumptions about behaviour and some of the myths that have grown up around this.

1.1 What is challenging behaviour?

It’s important that we qualify here what we mean by challenging behaviour. As a teacher, this doesn’t just mean dealing with violent or offensive behaviour; it’s any behaviour that disrupts normal classroom routine and the concentration of other learners. For the purposes of this book, we have grouped and refer to the different types of challenging behaviour, as either:

- Intimidatory behaviour: behaviour that is aggressive, offensive or violent towards others. This includes physical and psychological intimidation or verbal abuse.

- Inappropriate behaviour: behaviour that is more annoying than intimidatory, but is of such a persistent and prolific nature that it disrupts classroom routine.

- Non-participative behaviour: behaviour that is extremely passive or non-engaging, including refusal to participate in activities or intermittent patterns of attendance.

- Demanding behaviour: behaviour that is driven by the learner’s self-interest and conscious or sub-conscious desires to want to dominate what takes place in the classroom.

These definitions are fairly broad and issues of special educational needs and disabilities may dictate what is considered to be challenging or acceptable behaviour in the classroom. In this respect, individual organisations need to define what they consider to be behaviour that is challenging but acceptable, and behaviour that is challenging but disruptive to staff and other learners. It’s quite likely that even within the same institution there may be differences in individual teachers’ perspectives on the subject. A useful exercise, in this respect, is to look at the scenarios covered in Part C and discuss with colleagues what their view of the learner’s behaviour is and how they would have handled the situation.

1.2 Why does it happen?

Theories relating to understanding why people behave in the way they do date as far back as 500 BC and the Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle. Plato argued that people had an intrinsic desire to do what they do, whereas Aristotle’s view was that it is something that happens as a result of nurturing. The nature vs nurture debate is one of the oldest issues in human development that focuses on the relative contributions of genetic inheritance and environmental conditioning.

For many years, this was a philosophical debate with well-known thinkers such as René Descartes suggesting that certain behaviours are inherent in people, or that they simply occur naturally (the nativist viewpoint), arguing the toss with others such as John Locke who believed in the principle of tabula rasa, which suggests the mind begins as a blank slate and that our behaviours are determined by our experiences (the empiricist viewpoint). Towards the end of the 19th century, the debate was taken up by a new breed of theorists who developed the discipline of psychology.

For most of the early part of the 20th century, behavioural psychologists, such as Watson, Skinner and Pavlov, suggested that humans were simply advanced mammals that reacted to stimuli. Behaviourism remained the basis of human conditioning until it was challenged in the period between the two world wars by psychologists, such as Piaget and Vygotsky, who argued that the way we behave is a cognitive process in which individuals shape their own reaction to a situation rather than being told what to do. This gave rise to the movement known as cognitivism. After the Second World War, a third branch of theory, championed by people such as Maslow and Rogers, came into force with the belief that people were individuals whose behaviour should not be separate from life itself and who should be given the opportunity to determine for themselves the nature of their own actions. This became known as humanism.

The new millennium, and the growing interest in neuroscience, provided a fresh insight into how people react through their capacity to process external stimuli. Although theories around what role the brain plays in this process are still mostly speculative, there does appear to be common consent that the mind was set up to process external stimuli, to draw connections with other stimuli and, by making sense of what is happening, behave in what they consider to be an appropriate manner.

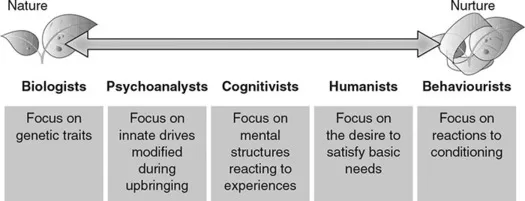

Few people these days would take such an extreme position in this debate as to argue for one side at the absolute exclusion of the other. There are just too many factors on both sides of the argument which would deter an all-or-nothing view. Figure 1.1 is a snapshot of the range of theories relating to this subject.

Figure 1.1 The nature—nurture theoretical spectrum

Here are some guidelines to determine where you might have a tendency towards in this debate:

- If you are at the extreme end of the Nature scale, the likelihood is that you will believe that the genetic structure of an individual’s brain is mostly responsible for their behaviour.

- As you start to move towards the centre of the scale, you begin to accept the viewpoint that the genetic structure of the brain is capable of being modified in response to reactions to experiences and the environment and that it is this that determines how people behave.

- Moving from the centre towards the end of the Nurture scale, you are likely to favour the ideas of the humanist theorists and the significance they attach to society’s influence on an individual’s behaviour.

- At the extreme end of the Nurture scale, the likelihood is that you will believe in the arguments of the behaviourists who suggest that all behaviour can be modified through conditioning.

There is no neat and simple way of resolving this debate. The more you read on the subject, the more confusing it gets. The best advice we can give is to go with what feels right for you. You could also try the exercise in Appendix 2 for some thoughts on this.

1.3 Who’s to blame?

We’d like to pause at this stage and ask you to reflect on where you consider the blame for disruptive behaviour lies. If you have an extreme naturist view, you will believe that learners have a disruptive behavioural gene. If however you are an extreme nurturist, then you will accept that learners’ reactions to the behaviour of others, including their teachers, influences their disruptive behaviour. Now, there’s an interesting suggestion: that learners’ disruptive behaviour could be as much a result of your actions as it is of theirs.

During our behaviour management sessions with trainee teachers, we do an exercise involving two cans of fizzy pop and lots of cleaning towels. We ask for four volunteers. Two are stooges who we have briefed what to do prior to the session. The other two are unwitting victims. The victims are given cleaning towels and asked to sit in chairs opposite each other about two metres apart. The stooges are each given a can of fizzy pop and asked to stand behind their intended victims.

We then read out the scenario in example 1.1, pausing after each extract for the stooges to shake their cans as the frustration that each of the central characters feel starts to build up.

Example 1.1: The story of two lives on a wet Monday morning in February

- A: Christine Adams is a 35-year-old teacher on the BTEC sports course at a local college. She was a B International Hockey player until she had to give up playing to look after her 7-year-old daughter, Amber, who has Down syndrome. She is a single parent. She gets up at 7:00am to make a cup of coffee and finds there is no milk (SHAKE).

- B: Joey Campbell is a 16-year-old student in Christine’s class. He was a former soccer trainee with the Derby Football School of Excellence and a promising prospect until a ligament injury ended his career. He lives with his mum and two younger sisters. His mother works as a cleaner at a local school. He has to get his sisters to school in the morning, He has to be awake at 7:00am. Desperate for a cigarette, he finds an empty packet (SHAKE).

- A: Christine’s childminder calls to say she has a rash and can’t look after Amber today (SHAKE).

- B: Joey’s younger sister can’t find her shoes and starts crying (SHAKE).

- A: Christine dashes round to her mother-in-law’s house to see if she can look after Amber. Reluctantly, the mother-in-law agrees but has a go at Christine for being a bad mother (SHAKE).

- B: As they get near to the school, Joey’s older sister tells him she has forgotten her gym kit. Joey has to run back to get it (SHAKE).

- A: Christine gets into class five minutes before the start of the lesson (SHAKE).

- B: Joey gets into class ten minutes after the start of the lesson (SHAKE).

- A: Christine asks Joey why he was late (SHAKE).

- B: Joey starts to explain (SHAKE).

- A: Christine says ‘excuses, excuses’ (SHAKE).

- B: Joey tries again to explain (SHAKE).

- A: Christine cuts him off (SHAKE vigorously).

- B: Joey storms out of the class (SHAKE vigorously).

At this point, we ask both of the stooges to ‘point the can of fizzy pop at their victims and on the count of three to open the can’. We’ve had people close their eyes at this stage, someone once screamed and someone even jumped out of the chair. Obviously, the stooges are briefed not to open the can. We’re sure that one day one of us will forget to brief them properly and be faced with a hefty cleaning bill.

The point of this exercise is to show that friction between teacher and learner in the classroom can arise as a result of the emotional state of either party. We ask the group to stay with the fizzy pop analogy and say how they can prevent their victims getting covered with pop. We usually get the following responses: Don’t shake the can so vigorously, leave the pop to settle down, get rid of the can or open it very slowly.

We then get them to come back to the scenario and discuss how Christine could have handled the situation better. We usually get that she could have:

- relaxed and listened to what Joey had to say

- explained that she’d had a bad start to the day and that they wipe the slate clean and start again

- postponed dealing with Joey till the end of the lesson when things may have cooled down

- stayed in bed.

If there is one common thread running throughout the dealings with all of the challenging characters included in Part C, it’s about understanding what the cause of their behaviour is and reacting appropriately to this. Showing that you are angry with someone isn’t always a good course of action but not necessarily always the wrong approach. Aristotle wrote that ‘anybody can become angry – that is easy, but to be angry with the right person, to the right degree, at the right time, for the right purpose and in the right way is not within everybody’s power and is not easy’. Get any one of these wrong and you could cause long-term damage to your relationship with the individual or, worse, be facing disciplinary action for harassment.

1.4 The myths of behaviour management

Never displaying anger towards a challenging individual is one of the myths that have grown up around the teaching profession. Aristotle says that it is okay to be angry with the right person at the right time for the right reason. Here are some other myths that we’d like to debunk:

Myth #1: Teaching is a virtue of character not intellect

No, you haven’t misread this. We are challenging Aristotle’s view of teaching and claiming that only intelligent teachers can be in control of the challenging children in their class. We need to qualify what we mean here.

Intellect has for many years been measured using Intelligence Quotient (IQ) tests. In more recent years, these tests have been criticised for failing to take account of the complex nature of the human intellect and the inference that there are links between intellectual ability and characteristics such as race, gender and social class.

In this section, we want to look at the theories of two writers who offered different perspectives on the subject of intelligence: Howard Gardner, who introduced the concept of multiple intelligences (1993) and Daniel Goleman, who introduced the concept of emotional intelligence (1996).

Howard ...