- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This is the ideal book to get you up and running with the basics of qualitative data analysis. It breaks everything down into a series of simple steps and introduces the practical tools and techniques you need to turn your transcripts into meaningful research.

Using multidisciplinary data from interviews and focus groups Jamie Harding provides clear guidance on how to apply key research skills such as making summaries, identifying similarities, drawing comparisons and using codes.

The book sets out real world applicable advice, provides easy to follow best practice and helps you to:

·Manage and sort your data

·Find your argument and define your conclusions

·Answer your research question

·Write up your research for assessment and dissemination

Clear, pragmatic and honest this book will give you the perfect framework to start understanding your qualitative data and to finish your research project.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

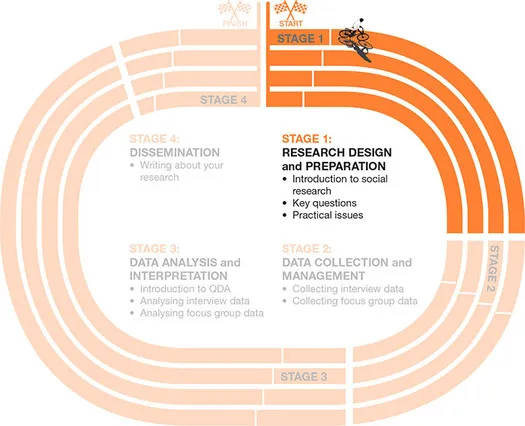

Introduction to Stage 1 Research Design and Preparation

Chapter 1 Introduction to Qualitative Social Research

- The many forms that social research can take

- What a research project might look like, from start to finish

- The range of settings where social research can be conducted

- The difference between methodology and methods

- The different principles underlying quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods and critical approaches

What is social research?

The chief conclusion of this report is that poverty is more extensive than is generally or officially believed and has to be understood not only as an inevitable feature of severe social inequality but also as a particular consequence of actions by the rich to preserve and enhance their wealth and so deny it to others. (Townsend, 1979: 893)

- the manner in which patients tell those close to them that they have cancer and the reaction of their family and friends;

- the difficulties that people face in returning to work after treatment;

- the willingness of people to support cancer charities after they have been successfully treated;

- the long-term impact on children if their parents do not survive cancer.

The idea is that developing valid knowledge about how society is organized or how we live our lives does not tell us how society should be organized or how we should live our lives. (Bachman and Schutt, 2012: 314)

Literature, secondary data and primary data

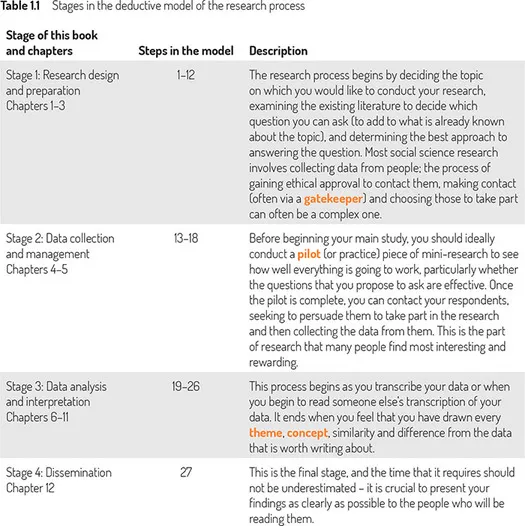

A model of the research process (deductive)

- Decide on the broad topic area to be covered by the research.

- Search through existing literature on the topic, looking both for practical findings and a discussion of the body (or bodies) of theory that can best aid understanding of the topic.

- Determine a research question which fits within a relevant body of theory and which, if answered successfully, will add to what is already known about the topic.

- Decide whether the research question could best be answered using quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods (the rest of this model assumes that the chosen methodology is qualitative).

- Consider which form or forms of data collection are most feasible and are most likely to contribute to answering the research question.

- Obtain permission for the research from the relevant ethics body or bodies (usually your own university).

- Determine who the respondents should be and whether they need to be contacted through one or more gatekeepers.

- IF THERE IS A GATEKEEPER: Seek to negotiate access with the gatekeeper(s).

- IF ACCESS CANNOT BE NEGOTIATED WITH THE GATEKEEPER: Keep trying until you find a group of respondents who you can gain access to.

- Obtain the best information available about the potential population of respondents.

- Determine whether it is possible to collect data from the entire population or whether a sample must be chosen.

- IF A SAMPLE IS NEEDED: Determine, and put into practice, the most appropriate sampling strategy.

- Prepare for the data collection, e.g. by drawing up topic guides and probes for interviews and focus groups.

- Pilot the data collection on people who will not be involved in the research; adjust the data collection and analysis methods where weaknesses are indicated.

- Approach the sample or population, explain the research to them and ask whether they are willing to take part, using as many ethically acceptable methods of encouraging participation as possible.

- For those who are willing to take part, send them information about the research, ask them to sign an ethics form and make practical arrangements to collect the data from them.

- If participation is lower than expected, consider ways that it can be increased such as offering incentives or recruiting further participants in a manner that is consistent with the original sampling strategy.

- Collect the data.

- Transcribe the data (you will usually do this yourself, unless you are fortunate enough to have funding to use a transcription service).

- Read through the data carefully before beginning to analyse it.

- Decide which approach(es) to analysis may be most appropriate, but be ready to review this decision in the light of the early experience of the analysis.

- Begin the analysis, while being reflective and making notes of key decisions.

- Take the early steps in the analysis, such as making summaries of cases and using the constant comparative method.

- Begin to reach simple findings about similarities and differences that are evident in the data.

- Search for more complex, conceptual findings.

- Undertake checks on the validity of your findings to ensure they accurately reflect the data.

- Produce the research output.

An example using the model of the research process (deductive)

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Why You Need This Book: Getting Started

- Introduction to Stage 1 Research Design and Preparation

- Chapter 1 Introduction to Qualitative Social Research

- Chapter 2 Designing Qualitative Research: Your Key Questions

- Chapter 3 Practical Issues in Qualitative Research

- Introduction to Stage 2 Data Collection and Management

- Chapter 4 Collecting and Managing Interview Data

- Chapter 5 Collecting and Managing Focus Group Data

- Introduction to Stage 3 Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Chapter 6 A Brief Introduction to the Analysis of Qualitative Data

- Chapter 7 Step One for Analysing Interview Data – Making Summaries and Comparisons

- Chapter 8 Step Two for Analysing Your Interview Data – Using Codes

- Chapter 9 Step Three for Analysing Your Interview Data – Finding Conceptual Themes and Building Theory

- Chapter 10 Analysing Your Focus Group Data

- Chapter 11 Alternative Approaches to Analysing Qualitative Data

- Introduction to Stage 4 Dissemination

- Chapter 12 Writing About Your Qualitative Research

- Appendix 1 Interview with Fern

- Appendix 2 Additional Material on Writing about Your Qualitative Data

- Glossary

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app