1.1 Behind The Facts And Figures

Research Focus

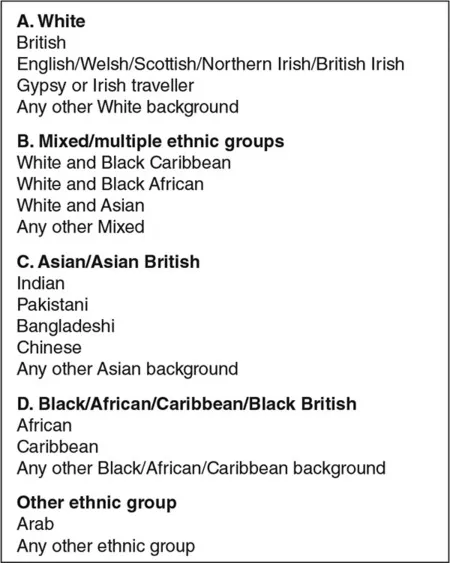

Since 2009, as part of the annual schools’ census data, the Department for Education has collected information about the languages spoken by pupils who attend mainstream schools. In 2018 (DfE, 2018), the figures showed that about 21.2 per cent of pupils in mainstream primary and 16.6 per cent in secondary schools in England were identified as ‘EAL’ (English as an Additional Language) learners. Figures for academies were only slightly lower. It is not easy to find a figure for the total number of languages currently spoken by pupils in schools in England, but it is thought to be about 350 (BBC, 2007). The proportion of ethnic minority pupils is different from those defined as ‘EAL’; currently this is around 33 per cent for primary schools and 30 per cent for secondary schools (DfE, 2018). The data on ethnicity come from the National Census, which is carried out every ten years. The most recent census was undertaken in 2011 and the categories for ethnicity used are shown in Figure 1.1 below.

The percentages for ethnic minority pupils are much higher than those for language diversity, so it is clear that there are many ethnic minority pupils in schools in England for whom English is not an additional language. But it is also clear that many pupils can be defined as both EAL and ethnic minority, because they belong to an ethnic minority group and also speak another language besides English. It is important to understand, especially for pupils such as those in this second group, that language knowledge and cultural knowledge are interlinked. This idea is discussed further in Chapter 2, along with the implications for teaching. There are also pupils who would ethnically be part of the ‘white’ majority but who could actually be defined as ‘EAL’, because they do not have English as their first language and their families are from countries where English is not the official language.

Figure 1.1 Categories of ethnicity in the 2011 National Census

Activity 1.1

Who are you?

In Figure 1.1, you can see the categories of ethnicity used in the 2011 national census. The categories change with every census, as the ethnic makeup of British society changes. Look at the categories and think about the following questions.

- Did you complete the most recent census? If so, which category did you place yourself in? If not, which category would you place yourself in?

- Could you place yourself into more than one category?

- Do you find it difficult to place yourself, and if so, why?

- Would it be difficult to place anyone you know?

- Would it be difficult to place any pupils you teach or have worked with?

- How do you think these categories were arrived at?

Despite the ever-increasing numbers of pupils from different ethnic and language backgrounds in our schools, the vast majority of teachers in England are still from ‘white British’ or ‘English’ backgrounds and do not speak other languages besides English. This means that most teachers who have pupils in their classes who speak other languages do not share those languages. This can sometimes feel like quite a challenge on top of everything else you need to know about and be able to do as a teacher. Vivian Gussin Paley (2000, pp. 131–2) in her book White Teacher describes her experiences as a ‘white majority’ teacher in a school with increasing numbers of pupils from diverse backgrounds. She soon realised that, in order to understand their needs and make the best provision for them, she had to understand more about her own identity and how it influenced her attitudes to her pupils. She concludes:

Those of us who have been outsiders understand the need to be seen exactly as we are and to be accepted and valued. Our safety lies in schools and societies in which faces with many shapes can feel an equal sense of belonging. Our pupils must grow up knowing and liking those who look and speak in different ways, or they will live as strangers in a hostile land.

Ethnicity is a very hard concept to define, and because we talk about ‘ethnic minorities’ we may sometimes think of it as a term only relevant for people who can be thought of as belonging to a ‘minority’ group. Of course, the reality is that we all have ethnicity. We all belong to different ethnic, cultural and social groups. But ethnicity in terms of language, ancestry and nationality is only one part of what makes us who we are. In your role as a teacher, thinking about your pupils, the notion of identity is a more useful one than ethnicity. It helps you think about all the factors that contribute to your individuality, and the personal and social issues that are so important in teaching and learning. As I suggest in Chapter 2, it is vital that you understand how your personal identity is an important aspect of your professional identity as a teacher, especially when you are teaching pupils from different language and cultural backgrounds from yourself. You need to understand how important (or not) your own ethnicity, language knowledge and other aspects of your personal makeup are to you, and how you might feel if any of them were threatened or undermined. This will help you understand the needs of the pupils you will be teaching. As Gussin Paley argues, this is an essential step to developing positive, trustful relationships with the pupils you teach and with their families.

The following activity will help you to think about your ‘ethnicity’ as part of your identity, in other words who you are.

Activity 1.2

How does it feel to be different?

You can do this activity on your own but it would be better if you could do it as a group discussion task, with some of your fellow trainees or colleagues in a school setting.

- First, look at the census categories and think about how you would define your own identity. Is it enough just to think about your ‘ethnic background’ as defined in the categories of the census? What other aspects of your identity are important to you? Where your family comes from might be an important part of your identity, but what else might count for you?

- Make a list of 6–8 attributes that you would say were important aspects of your identity. Compare your list with those of your colleagues.

- Can you think of a time when you were made to feel different and that you did not belong? This could have been when you were a child or as an adult in a work situation or in a social context. What did you feel was different about you? How would the quote from Vivian Gussin Paley reflect your feelings? Write a few sentences about how it felt to feel different and perhaps excluded.

1.2 ‘Superdiversity’ In England

In about 120 AD, soldiers from the Roman Empire built a fort at the mouth of the river Tyne and named it Arbeia (Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums, 2018). You can still see the remains today in South Shields near Newcastle upon Tyne. Some historians think the Romans who lived in the fort named it after their original homelands in what are now Syria, Libya and Spain. Britain has always been multicultural and multilingual – a small island which has experienced successive waves of immigration and emigration from and to all over the world. The English language reflects this, as it contains words from all the languages of the people that have come to this island and enriched its vocabulary over the centuries.

Over recent years, the population of England has changed greatly. The addition to the EU of the A8 ‘accession countries’ in 2004 meant that people travelled within Europe much more than they used to. It has become quite normal for people from Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and other eastern European countries to come to England to work, and then return to their countries of origin or move on elsewhere. This has been described as ‘circular migration’ and is a worldwide phenomenon. Migration has also been influenced by other global events. Many British cities now are what have been called superdiverse com...