![]()

1 Introduction: The Basics of Social Science Research Designs

This chapter introduces the most important elements of research designs in the social sciences, each of which will be discussed at greater length in the subsequent chapters. In addition, it explains the differences between deductive and inductive approaches to constructing a research project, and the differences between explanatory and interpretative research designs, as well as those that exist between x-centered and y-centered research projects.

This introduction gives an overview of the basic social science elements and key concepts of explanatory research designs. Accordingly, it is recommended for first-time researchers as well as graduate students, PhD candidates, postdoctoral researchers, and scholars of the social sciences that seek to refresh their knowledge about the basics of social science research. Chapter 2–8 explain the various choices graduate students, PhD candidates, postdoctoral researchers, and scholars of the social sciences can make in the course of designing a deductive, explanatory research project and which choices are best suited for a particular project.

This book can be used in two ways. First, it offers guidelines on how to set up a social science research project that is deductive and explanatory in character from start to finish using a step-by-step approach. Starting with finding a good research question (Chapter 2), selecting theories and hypotheses (Chapter 3), choosing the methodological set-up of the project (Chapter 4) and selecting cases (Chapter 5), making choices between methods of data collection (Chapter 6), and choosing qualitative or quantitative methods of data analysis (Chapter 7 and 8), it explains the choices you will face at each crossroad and the various implications these choices will have for your next steps in setting up a sound social science research project. Thus, it is recommended that first-time researchers read the book on a chapter-by-chapter basis.

Second, graduate students, PhD candidates, postdoctoral researchers, and scholars of the social sciences that are already experienced in deductive explanatory social science research can use this book as a problem-solving and decision-supporting device. Those who are grappling with a particular element in designing social research projects can directly consult the corresponding chapter in this book, in order to gain an overview of the choices that can be made as well as their respective implications.1

Deductive and Inductive Research

While natural sciences study the material world, social sciences study the social and political world. Social sciences constitute a broad field, including subjects such as political science, communication studies, sociology, international relations, or comparative regionalism.

The starting point for social science research is a research question, i.e. a single sentence ending with a question mark that specifies what exactly the research project seeks to inquire.

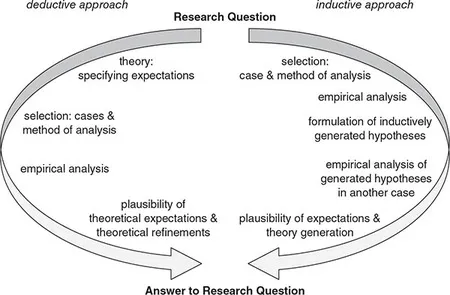

In general, there are two different strategies for answering research questions. Social science research can be inductive or deductive in nature (King et al. 1994b, Bryman 2008, Creswell 2014). In short, inductive research resembles a ‘bottom-up’ approach, while deductive research resembles a ‘top-down’ approach (Rucht 1991, Bryman 2008, Svensson 2009, Marshall and Rossman 2011). This means that inductive research starts answering the research question by beginning with the empirics in conducting an explorative study, while deductive research starts with theories and only subsequently shifts towards empirics (see Figure 1.1).

As the figure shows, a deductive project starts out by developing a scientific answer to a research question on the basis of existing theories. Theories are used to specify hypotheses, which are later on operationalized and put through a thorough empirical examination based on sound methods. On the basis of the insights obtained via the empirical analysis of the hypotheses, existing theories can be refined (or new theories can be developed).

Deductive research designs are theory-based in character (King et al. 1994b, Bryman 2008, Creswell 2014). Whenever a research question relates to a phenomenon that has already been studied (albeit with a different focus) by other scholars, it is very likely that there are already theories that relate to a question/phenomenon of interest. Thus, in such situations, it is a good idea to opt for a deductive rather than inductive research design. In order to scientifically answer a research question, you need to select theories and develop hypotheses on this basis, which are subsequently empirically examined in a methodologically sound manner. As a result of this endeavor, you will be able to reject one or more of the explicated hypotheses or find empirical support for one or more hypotheses. Very often, deductive research projects allow for refinements (for example in specifying causal mechanisms or scope conditions) of the theories that you started out with, leading to generalized insights.

Figure 1.1 Deductive and inductive research processes

An inductive project develops a scientific answer to a research question on the basis of empirical analysis of explicated, initial assumptions (explorative study). On the basis of the insights obtained in the explorative study, hypotheses are formulated. The inductively generated hypotheses need to be examined in a second case/additional cases, in which the hypotheses undergo a thorough empirical analysis based on sound methods. On this basis, existing theories or hypotheses can be refined (or new theories and hypotheses can be formulated).

Hence, inductive research also takes a research question as a point of departure, but the second step is not to select theories in order to formulate hypotheses that can be empirically examined (Bennett and George 2006). Instead, inductive research projects clarify the assumptions the researcher makes about what might answer the research question, select the case and specify the methods of analysis in order to subsequently conduct the explorative case study and explore the dynamics at play. Ideally, the inductively discovered findings are then explicated (e.g. in the form of a hypothesis) and empirically examined in another case or other cases. This last step is essential, because what you think is a generalizable insight on the basis of one explorative case study might, in fact, be only applicable to this one case (e.g. if the initial explorative case was an outlier). Only if the explanation also holds in other cases than the one from which the hypothesis was generated in the first place can the findings be generalized, and the hypothesis regarded as plausible.

Inductive research is essential in instances in which existing theories cannot easily be applied to the phenomenon of interest. Yet it is advisable to opt for a deductive research design whenever there are theories that can be utilized for answering a research question.2 Also inductive research designs are well-suited if you are interested in a phenomenon that is not yet in the forefront of research, for instance because it was a singular event that has only recently taken place. For example, if you are interested to explain why Donald Trump was nominated as the Republican candidate for the US presidency in 2016 or why Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, an inductive explorative study can be a good starting point. Yet, good inductive research examines the insights gained in the explorative case studies in other cases in order to contribute to general knowledge about populism in elections or about annexations in international relations more generally.3

As a rule of thumb, explanatory research projects usually follow a deductive logic (see below). Explanatory projects typically ask ‘why’ questions in order to uncover relationships between phenomena. Only in rare exceptions do explanatory projects use inductive research designs (usually only when there are no theories that fit well with the phenomenon of interest). By contrast, interpretative research projects are often following an inductive logic. Typically, interpretative projects ask ‘how is this possible’ questions in order to reconstruct how specific outcomes became possible (see next section). Note that the chapters that follow exclusively focus on deductive, explanatory research projects.

Explanatory and Interpretative Research Designs

Explanatory and interpretative research differs concerning the epistemological grounding as well as the types of research questions that are pursued. Epistemology, or theory of knowledge, deals with the question of what we can know and how we can establish whatever type of knowledge is possible. In the social sciences, there are essentially two extreme camps: positivists and postmodernists (Popper 1968, Giddens 1975, Smith et al. 1996, Klotz and Lynch 2007). The former claim that social sciences are normal sciences and, like natural sciences, can generate knowledge about cause–effect relationships (Popper 1968).4 The latter argue that we cannot make any causal inferences (Chalmers 1982, Elster 1989) because, unlike the natural world, there are no law-like relationships in the social world as the social sciences are not concerned with ‘material facts’. Instead, social sciences deal with ‘social facts’ which are social constructions (e.g. state, society, power) and which are often based on human behavior which can change situationally (e.g. due to emotions, cognitive short-cuts, changes in strategic orientation, changes in identities, changes in perceptions) (Wendt 1998).

These extreme positions have informed the current epistemological debate in the social sciences, in which both positions are no longer articulated in such a radical manner (King et al. 1994a, Van Evera 1996, Kellstedt and Whitten 2009, Gerring 2011, Kincaid 2012). Instead, most of social science research adopts middle ground positions, leaning towards a positivist or post-positivist epistemology without fully subscribing to or fully rejecting the narrow notion of natural science causality.

Leaning towards the positivist side are rationalist approaches to social sciences. They recognize that we do not live in a mono-causal social world, that humans as social beings do not always behave in the exact same manner, and that social scientists can typically not achieve perfect laboratory conditions. Nevertheless, rationalists assume that insights about likely cause–effect relationships can be gained, when the research design approximates ceteris paribus assumptions. Thus, in the social sciences, rationalists do not usually claim that causal effects will always unfold in the exact same manner, and consequently often focus on the plausibility, likelihood, or probability of findings instead of the truth. Also, they do not usually use language such as ‘proving a theoretical expectation as correct’, but instead talk about ‘finding empirical support for a theoretical expectation’ or ‘concluding that a particular expectation is plausible’ or that it a specific effect is ‘likely’ or ‘probable’.

Leaning...