![]()

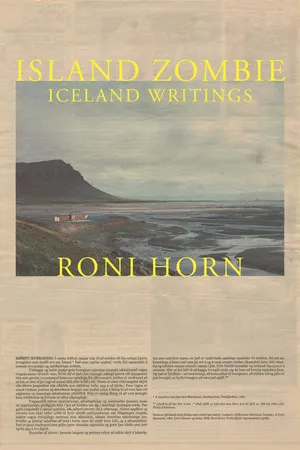

MORGUNBLAÐIÐ NEWSPAPER

(1998–2003)

![]()

Note on Texts

The texts included in this section were written for Morgunblaðið, Reykjavík. At the time, Morgunblaðið was Iceland’s only nationally distributed daily newspaper.

“The Nothing That Is”

“Notes on Icelandic Architecture” (Excerpt)

“One Hundred Waterfalls, Five Hundred Jobs”

Iceland’s Difference

A series of 23 visual editorials. Weekly publication began on April 6, 2002. Each installment occupied page 16, the last page of Lesbók, the weekend culture section.

All texts were published in Icelandic. Translations by Fríða Björk Ingvarsdóttir.

![]()

THE NOTHING THAT IS

I grew up with trees. I count them among the most important things in my life. But oddly, when I come to Iceland with its treeless landscape, I never miss them. Over the years of travel here the open, unobstructed views of the island have become very important to me. These views are the trees of Iceland. Because one of the great qualities of the tree is its way of relating things: the earth to the sky, the light to the dark, the wind among its leaves to the stillness that surrounds it, the small spaces within the tree to the vast spaces it inhabits. Here in Iceland the view takes on this role and in doing so expresses a wholly unique sense of place. The weather is a big part of this sense of place and a view here is never without it. It allows a glance at the rolling past and sometimes what’s to come. The view contains the distant and the near often with equal clarity. It lays out the shape of the planet with an expansiveness and transparence that exists in few other places. It holds you in a solitude that enlarges you. The view relates you to a world that is mostly a world of natural things: rocks and vegetation, and water, complex, multifarious things that are also remarkably young.

I grew up in New York City and its early suburbs. My first trip abroad brought me to Iceland in 1975 when I was nineteen.

Since then, the roads, especially rough (but having a way of keeping a traveler in close contact with the land both physically and psychologically) have been primed for faster, more convenient travel. With the paved road and accelerated rate of passage I notice my relationship to the land becoming more distant, even abstracted. To maintain contact with it requires greater responsibility on the part of the traveler. This seems a small price to pay for the extensive quality-of-life enhancements such development brought.

Among the many advantages that Iceland enjoys is its unique position in history relative to those of other modern cultures. Because Iceland has experienced delayed economic development the country is fortuitously out of sync. You are out of sync because your environment, unlike those of other modern societies, is still intact. This places the country now, at the end of the second millennium, in a critical position to observe the destruction that other societies have brought upon their environment through flawed and unchecked development and exploitation of natural resources.

Iceland is in a position to bear witness to these dubious fruits. And with this knowledge it must question the extent and nature of development it wishes to pursue. Unlike other cultures whose major development is yet to come, Iceland does not suffer from rampant illiteracy or ignorance brought about by a censored press. You do not suffer pervasive poverty, overpopulation, or recurring natural disasters in the form of drought or floods or unchecked disease.

Up until very recently it seems that exploitation of natural resources has been limited by the size of your economy. But now, as the economy grows, society is more willing to consider ever more invasive methods of expansion in the service of ever-increasing levels of affluence. And with this new potential a greater willingness and most definitely a greater technological capacity to alter nature is pressed forward as a necessity.

As a foreigner I have watched with admiration Iceland’s persistent refusal to allow foreign influences to compromise your language. I have admired the extraordinary literature that you have invented and that is such a profound part of your identity. I have also admired your early architecture and indigenous building, much of which is unique to your culture. And then there are the many enlightened aspects of your social culture, among the most notable of which are the pragmatic tolerance of intimate union and the responsibility taken for its outcome.

But now when I come to the island I wonder whether you see the fast rate of change that your society has undergone, especially in the last fifteen years, and how it now begins to affect the fragile ecologies that surround you. The nature that surrounds you is especially fragile and especially glorious because it is unusually young. As a result, your capacity to alter and destroy nature is greater than ever before.

Modern society has experienced a seemingly uncontrollable appetite for consumption, well in excess of individual need. The resultant overexploitation of natural resources has destroyed many underlying organic equilibria. This fact is now experienced in part with ever more frequent catastrophic events of weather as well as pollution, in the form of both toxins and invasive manipulations of the environment. Iceland is in a unique position to make choices that will bear profound influence on your identity as a people. It is a choice that must reflect your knowledge of other cultures and how they have, initially through ignorance and then through wantonness, destroyed their environment. In the United States, for a large portion of the population one’s health is no longer one’s own. It is degraded by toxins that though unseen are so pervasive they cannot be kept out of the body. These are choices that must assess the real value of development not just in physical and quantitative terms but in spiritual and psychological terms, as well. Many post-industrial—and/or overpopulated—countries have polluted their waters, their land, and their air, in some places to an extent that makes them uninhabitable. It is a pollution that is toxic and most often irreversible, a pollution that has deeply undermined quality of life. It is also a pollution that destroys humanity even as humanity fights for the right to pollute.

Excessive development and the overuse of natural resources is a choice. It is not based in necessity. Development that results in the introduction of pollution to the Icelandic environment cannot be regarded as a viable option. It will ultimately, though perhaps not immediately, degrade it. Today, when you look out over the ocean that so fortunately surrounds you, you have the knowledge that other cultures may not have had or did not care to respect. You have the choice to implement the use of renewable resources to sustain your economy. You have the choice to utilize less invasive methods of production and the choice to produce things that do not result in irreversible damage to your environment.

This essay is motivated in particular by my fear of the loss of the Highlands. But as I write I see that it applies to the island’s ecology as a whole. With each visit to Iceland I become ever more anxious concerning these issues. Yesterday as I was driving out of Reykjavík I was shocked to find myself comparing the view out my window to that of New Jersey in the early sixties. As an artist, to me Iceland has borne a deep influence in my professional development. And as an artist, this is a deeply personal matter as well. Over the years I have felt the necessity for my returns here growing greater still.

Which brings me to the crux of the matter, the potential loss of the Highlands. It won’t happen right away. First you will build a dam in some remote corner. (In the belief that you can power X, Y, and Z industries, in the belief that you can expand your economy and increase your affluence. You won’t concern yourself now with the fact that these industries will most likely pollute the water and the air. You won’t discuss the fact that this is really the first of many dams.) Then you will flood a valley. (Never mind that it is the only valley like it in the world. Perhaps you will convince yourself that the resulting lake has its own beauty, perhaps even accept it as more nature—even though you know it is really artifice.) Along with the dam will come the roads and other civil infrastructures. (You will drive these roads and imagine a truly wild place—perhaps one that no one has ever been to before—but in reality these roads will turn the whole of the interior into a parody of itself. Now it is merely more domesticated space.) Along with the roads comes greater access for everyone, and along with this access, a level of use that will quickly dominate and subdue the wild and unknown.

The Highlands, while often referred to as a vast, empty space, is neither vast nor empty. The American poet Wallace Stevens names precisely what the Highlands is so profoundly full of in his poem “The Snow Man.” He writes:

For the listener who listens in the snow

And nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.*

In my experience the Highlands is one definition of the nothing that is. And the nothing that is synonymous with the real. The real cannot be mitigated without destroying it. The Highlands is not for everyone. To enhance its accessibility is to deny what it is. An individual who wishes to travel the Highlands must be equipped both psychologically and physically—and not the other way around. The Highlands is a desert, it will take your measure. It cannot be made into a place for the casual visitor.

Your Highlands, while lauded as the single largest unexploited block of land in Europe, is, relatively speaking, tiny, not even the size of Ireland. Once you have compromised it, in a matter of one generation or two at the most, your identity as a people will be altered. Iceland will become a place dominated by human presence. The balance of identity will tip—away from the majestic solitude of the interior—away from a place largely unoccupied, uninhabited, unaltered—away from the possibility of a place more clear and clean and pure than not—away from a place that expresses vastness and absoluteness, and all that exceeds us— away from a place that is exquisitely distinguished simply in being what it is— away from the many, many things I come to this island to experience. These are the things Icelanders have been nurtured on, perhaps unknowingly, that give this culture its remarkable difference, and its utterly unique sense of place.

With this change Iceland will simply become more like the rest of this mostly compromised world—dominated by a humanity that can only value nature as something to be exploited.

Iceland has a choice. The destruction of the Highlands is not necessary to...