eBook - ePub

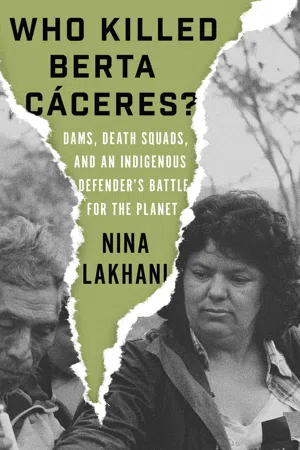

Who Killed Berta Cáceres?

Dams, Death Squads, and an Indigenous Defender’s Battle for the Planet

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Who Killed Berta Cáceres?

Dams, Death Squads, and an Indigenous Defender’s Battle for the Planet

About this book

The very first time Honduran environmental activist Berta Caceres met the writer Nina Lakhani, Caceres said, "The army has an assassination list with my name at the top. I want to live, but in this country there is total impunity. When they want to kill me, they will do it." In 2015, Caceres won the Goldman prize, the world's leading environmental award, for her leadership of indigenous organizations against illegal logging and the construction of four giant dams. The next year she was murdered.

Lakhani tracked Caceres's remarkable career in the face of years of threats--two fellow environmental campaigners were killed before her--and the journalist also endured threats and harassment herself. She was the only foreign journalist to attend the 2018 trial of Caceres's killers, where security officials of the dam builders were found guilty of planning her death. Many questions about who ordered the killing remain.

Drawing on years of familiarity with Caceres, her family, and her movement, as well as interviews with company and government officials, Lakhani paints an intimate portrait of a remarkable woman as well as a state beholden to both corporate control and US power.

Lakhani tracked Caceres's remarkable career in the face of years of threats--two fellow environmental campaigners were killed before her--and the journalist also endured threats and harassment herself. She was the only foreign journalist to attend the 2018 trial of Caceres's killers, where security officials of the dam builders were found guilty of planning her death. Many questions about who ordered the killing remain.

Drawing on years of familiarity with Caceres, her family, and her movement, as well as interviews with company and government officials, Lakhani paints an intimate portrait of a remarkable woman as well as a state beholden to both corporate control and US power.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Who Killed Berta Cáceres? by Nina Lakhani in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Global Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Counterinsurgency State

Río Blanco, April 2013

Dressed in her customary getup of slacks, plaid shirt and wide-rimmed sombrero, Berta Cáceres stood on top of a small grassy mound shaded by an ancient oak tree to address the crowd of men, women and children who’d walked miles from across Río Blanco to discuss the dam. ‘No one expected the Lenca people to stand up against this powerful monster,’ she proclaimed, ‘and yet we indigenous people have been resisting for over 520 years, ever since the Spanish invasion. Seventy million people were killed across the continent for our natural resources, and this colonialism isn’t over. But we have power, compañeros, and that is why we still exist.’

Río Blanco is a collection of thirteen campesino or subsistence farming communities scattered across hilly, pine-forested terrain in the department of Intibucá, a predominantly Lenca region in south-west Honduras. Here, extended families work long days, farming maize, beans, fruit, vegetables and coffee on modest plots of communal land which are mostly accessible only on foot or horseback. Chickens and scraggy dogs dart in and out of every house. Some families also raise cattle, pigs and ducks to eat, not to sell, as there are few paved roads or transport links connecting the communities with market towns. Since being given the land by a former president in the 1940s, these communities have largely been ignored by successive governments – despite election promises to deliver basic health and education services and paved roads.1 With few public services, the communities rely on the Gualcarque River, which flows north to south, skirting the edge of Río Blanco. The sacred river is a source of spiritual and physical nourishment for the Lenca people. It provides fish to eat, water for their animals to drink, traditional medicinal plants, and fun: with no electricity, let alone internet, the children flock to the river to play and swim. The communities live in harmony with the river and with each other. Or at least they used to.

The pro-business National Party government licensed the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam in 2010, ignoring the legal requirement for formal consultation before sanctioning projects on indigenous territory. Not only that, the environmental licences and lucrative energy contracts were signed off at breakneck speed without proper oversight, suggesting foul play by a gaggle of public officials and company executives. In Honduras this wasn’t unusual: the Gualcarque River was sold off as part of a package of dam concessions involving dozens of waterways across the country in the aftermath of the 2009 coup – orchestrated by the country’s right-wing business, religious, political and military elites to oust the democratically elected President Manuel Zelaya. Not just dams: mines, tourist developments, biofuel projects and logging concessions were rushed through Congress with no consultation, environmental impact studies or oversight, many destined for indigenous lands. The process was rigged against communities; the question was how high did the corruption go.

The hydroelectric project would dissect the sacred river and divert the water away from local needs, generating electricity to be sold to the national energy company (ENEE). The Lenca people knew that without the river, there could be no life in Río Blanco.

That’s why, a few days before Berta’s visit, community members had set up a human barricade blocking road access to the Gualcarque in a last-ditch effort to stop construction going ahead.

Berta addressed the crowd that April day just a stone’s throw from the makeshift roadblock, which was manned in shifts by families utterly fed up with being treated like intruders on their own land. The blue and white flag of Honduras hung between two wooden posts obstructing the gravel through-way. The community had first sought help from COPINH several years earlier. Berta and other COPINH leaders helped them petition local and national authorities, the dam building company Desarrollos Energéticos SA (DESA) and its construction contractor, the Chinese energy giant Sinohydro, making it crystal clear that they did not want the river they relied upon for food, water, medicines and spiritual nourishment to be dammed. Lavish promises by DESA to build roads and schools turned out to be empty. The people held meetings, voted, marched on Congress and launched judicial complaints against government agencies and officials.

But the mayor of Intibucá, Martiniano Domínguez, claimed resistance was futile. The dam was backed by the president, he said, and they should be grateful to DESA, which promised jobs and development for the neglected community. Domínguez green-lighted construction in late 2011, after falsely claiming that most locals favoured the dam. A crooked consultation deed – filled with the names and signatures of people overtly against the dam, and others who couldn’t read or write – was used as proof of community support to shore up permit applications and investments. When heavy machinery rolled in, cables connecting a solar panel to the school’s internet and computer servers were destroyed, fertile communal land was invaded, and maize and bean crops on the riverbank were ruined, while well-trodden walking paths were blocked off. Signposts appeared around the construction site: ‘Prohibited: Do Not Enter the Water’. For many, this humiliation was the last straw.

Berta only found out later, perhaps too late, that the dam project was backed by members of one of the country’s most powerful clans, the Atalas, and that the president of DESA and its head of security were US-trained former Honduran military officers, schooled in counterinsurgency. This doctrine had long been used across Latin America to divide and conquer communities resisting neo-liberal expansion. But Berta grew up during the Dirty War, and by the time of her address at El Roble she had twenty years of community struggle under her belt. She understood the risks of opposing big business interests, and wanted to make sure the people of Río Blanco understood them too.

‘Are you sure you want to fight this project? Because it will be tough,’ she told them from the grassy mound beneath the oak tree. ‘I will fight alongside you until the end, but are you, the community, prepared – for this is a struggle that will take years, not days?’ A sea of hands rose into the air as the crowd voted to fight the dam.

Standing nearby was the figure of Francisco ‘Chico’ Javier Sánchez, a squat, moustachioed community leader in a black cowboy hat. ‘Berta warned us that opposing the dam would mean threats, violence, deaths, divisions, persecution, infiltrators, militarization, police, sicarios, and that everything would be done to break us. COPINH was ready to support us in peaceful protests and actions, but it had to be our decision, the community’s, because it was us who would suffer the consequences. We were totally ignorant, but she was very clear. Everything she told us that day came true, and worse.’

Three years later, five Río Blanco residents were dead, and so was Berta Cáceres.

Role Models

Berta’s mother, Austra Berta Flores López, is a staunchly Catholic, no-nonsense matriarch and was the most important role model in Berta’s life. Born in 1933 in La Esperanza, Doña Austra is a nurse, midwife, activist and Liberal Party politician, descended from a long line of prominent social and political progressives who were maligned and persecuted as communists during a string of repressive dictatorships. I interviewed the straight-talking Doña Austra several times, before and after Berta’s murder – always at the spacious single-storey colonial-style house she built in the early 1970s, and always while drinking sweet black coffee in her legendary parlour adorned with religious knick-knacks and old photos. It’s in this room that Doña Austra has, over the past four decades, hosted a motley crew of colourful characters including Salvadoran guerrilla commanders, Cuban revolutionaries, Honduran presidents and American diplomats. If walls could talk!

La Esperanza, which means ‘hope’ in Spanish, is a picturesque place in the hills surrounded by sweet-smelling pine forests and dozens of small villages. Lying 120 miles west of the congested concrete capital, Tegucigalpa, at the end of a snaking road riddled with potholes, it is the coolest and most elevated town in Honduras. Politically the set-up here is slightly odd, as La Esperanza merges seamlessly with the city of Intibucá; they are divided by a single street but administered by separate municipal governments. Intibucá is the older of the twin cities, and traditionally Lenca. La Esperanza houses the newer mestizo or ladino community; Berta’s maternal great-grandparents (from Guatemala and the neighbouring department of Lempira) were among the first mid-nineteenth-century settlers. Growing up, Doña Austra witnessed the strict ethnic apartheid that banned indigenous inhabitants of Intibucá from entering mestizo schools and churches in La Esperanza.

As a little girl, Austra travelled on horseback to visit her father in El Salvador where he was intermittently exiled during the dictatorship of General Tiburcio Carías Andino (1933– 49). ‘We’d load one beast with food like dried meat and tortillas, the second one my mother and me would ride for two days to reach my father,’ she recalled. ‘I come from a family of guerrillas. Some ended up in chains as political prisoners, others were exiled or killed. My family has always fought for social change, and for that we were labelled communists.’

Austra Flores was widowed at the age of fifteen, after three years of marriage to a much older man. Then she trained as a nurse, and later as a midwife. In those days she was often the only health professional in town, so patients would walk miles to the house and wait on benches lined up on the shaded front porch and back patio. Many were impoverished campesinos who brought a hen, some firewood or a sack of maize as payment in kind. ‘We didn’t have much money, but there was always enough to eat,’ said Doña Austra, who even now keeps her leather medical bag handy for when patients turn up. Some still walk miles, and they still wait on the very same wooden benches.

By the mid-70s, student rebellions were part of a burgeoning human rights scene in which Berta’s older brother Carlos Alberto, Austra’s fifth child, from a different relationship, played a role. Elected student leader of the La Esperanza teacher training college, the Escuela Normal Occidente, he led a hunger strike to oust the abusive and ineffective director. When he was shot in the left shoulder by soldiers deployed to evict striking students at the college, Doña Austra rushed him to Tegucigalpa for surgery.

The injury inspired Carlos to be more than a local student activist. He led nationwide strikes forcing a string of rotten head teachers to resign, and convoked clandestine meetings at the family home to organize hands-on support for leftist guerrilla groups in neighbouring El Salvador and Nicaragua. His belligerent leadership was noted, and the family became targets for the feared state intelligence service, the Dirección Nacional de Investigación (DNI).

‘The house would be surrounded by orejas [Spanish for ears, meaning informants], it was always under surveillance and we’d hear boots on the roof. Soldiers and DNI men would come in and search the house, but they never looked in there,’ said Austra, showing me the wooden wardrobe in the bedroom where they once hid books and pamphlets considered subversive. ‘If the DNI had found those, we would have been taken away to the 10th Battalion base [located in nearby Marcala] where Salvadorans looking for supplies or safety were locked up and disappeared.’

Several of Carlos’s friends, other student leaders, were disappeared during the 1970s, by which time Austra’s house was the de facto socialist (with a small ‘s’) headquarters, used to store medicines and food for the Salvadoran guerrillas and hide their commanders. She also hid young men, boys really, seeking to avoid the military conscription that wasn’t abandoned until 1995. Francisco Alexis, her eighth child, was jailed, starved and tortured at the 10th Battalion base after he too tried to escape military service. ‘Francisco was so traumatized by the barbarities inflicted on him, we sent him to live in the US,’ said Austra. He was smuggled out using fake ID.

After graduating as a teacher, Carlos joined the Communist Party and moved north to the Bajo Aguán region, to work with campesino banana cooperatives campaigning for land redistribution. According to Doña Austra, he got involved in the armed student guerrilla group Los Cinchoneros, also known as the Popular Liberation Movement, founded in rebellious Olancho in eastern Honduras. Carlos moved to Russia with a scholarship to study history and political science. He was later in Nicaragua, defending the Sandinista revolution against the US-armed Contras. For Berta, Carlos was a real-life revolutionary idol.

Berta Isabel Cáceres Flores was born on 4 March 1971, a chubby, placid baby Doña Austra’s twelfth and last child. Her father José Cáceres Molina (biological father of the four youngest siblings), from the nearby coffee-growing town of Marcala, was an abrasive ex-infantry sergeant from a staunchly nationalist family.2 José Cáceres walked out when Berta was five, after imposing years of what many family members called ‘alcohol-fuelled misery’ on them, and she had little contact with him while growing up. Berta was a sparkling little girl with thick curly hair and a wide smile. By the age of seven or eight she was a regular competitor on the local beauty pageant circuit, picking up prizes as the best-dressed Mayan princess and Señorita Maize. She liked to play football, choreograph dances and put on plays, showing a notable flair for organizing and bossing the other children. But she also grew up running in and out of secretive, politically charged meetings, and from a young age was spellbound by the fiery debates centred on injustices in her corner of the world. By then, in the early to mid-1980s, Austra was involved in fledgling rights groups like the women’s collective, Movimiento de Mujeres por la Paz ‘Visitación Padilla’,3 and helping to organize against the US-backed death squads operating across Central America. Thanks to Austra’s dedication as a community midwife, Berta also saw first hand the miserable conditions endured by neglected hill communities.

Aged twelve or thirteen, she would walk miles with her mother to reach pregnant women in isolated rural cantons with no electricity or running water. Berta assisted: she would fetch hot water and towels, hold candles for light, and sometimes even cut the umbilical cord. Many women spent hours each day collecting clean water and firewood as well as working in the fields and raising children, with no access to contraception or antenatal care, and no escape from violent partners. The grim plight of rural women left its mark on both mother and daughter. Later, Berta came to understand these harsh realities as a local consequence of global rules, a vision which would define her.

Sometimes they travelled to the Colomoncagua refugee camp, forty miles south of La Esperanza, to help pregnant Salvadoran civil war refugees living in concentration camp conditions. These mother–daughter medical missions provided good cover, allowing them to deliver food and medicines, and then sneak out messages for Salvadoran rebel commanders lying low at the family home. The first refugee camps in Honduras opened in early 1981, just as the US (with the aid of military dictatorships) started rolling out the counterinsurgency doctrine, in what Ronald Reagan called ‘drawing the line’ in Central America.4 From this point forward, any Honduran suspected of sympathizing with neighbouring communist revolutionaries risked being murdered or disappeared by US-trained elite soldiers. This disposition to fight American enemies was established as a core characteristic of Honduran military ethos.

It’s worth noting that anti-communist fervour was not a Cold War invention. In the first half of the twentieth century, Central America’s elite landowning families – who enjoyed absolute economic and political power in their regional fiefdoms – were more than comfortable branding popular uprisings as communist threats. Any sniff of a political, social or labour movement demanding even modest reforms to tackle the stark inequalities was crushed, often brutally, to protect the interests of these elites.

In neighbouring El Salvador, the 1932 peasant uprising was ruthlessly quelled, leaving around 30,000 mainly indigenous Pipil people dead.5 In Honduras, the 1975 Los Horcones massacre in rebellious Olancho was one of the worst to be documented. By then, the north coast had been devastated by Hurricane Fifi,6 and campesinos on the brink of starvation squatted on unused arable land in the hope of forcing agrarian reforms. The crackdown was prompt. At least fourteen campesinos, sympathetic clergy and students were rounded up, tortured and killed by soldiers and armed guards on the orders of local landlords unwilling to relinquish a single plot. The dismembered bodies were found buried on land belonging to local rancher José Manuel Zelaya Ordóñez,7 father of the future (subsequently deposed) president, Mel Zelaya Rosales. Thus when the US entered into full-fledged Cold War paranoia, the anti-com...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- 1. The Counterinsurgency State

- 2. The Indigenous Awakening

- 3. The Neo-liberal Experiment

- 4. The Dream and the Coup

- 5. The Aftermath

- 6. The Criminal State

- 7. The Threats

- 8. Resistance and Repression

- 9. The Investigation

- 10. The Trial

- Afterword

- Notes

- Acknowledgements

- Index