![]()

PART 1

Guiding Frameworks

![]()

1

Introduction

What’s in a Name?

Jody S. Nicholson, F. Dan Richard, and Christian Winterbottom

Nearly 100 years ago, the conceptualization of teaching and learning in the United States was challenged and advanced by the work of John Dewey (Dewey, 1933). Dewey’s theoretical framework continues to inspire the connection between the community and education in modern pedagogical practice. Despite the popularity of Dewey’s experiential education model, universities are still grappling with how to integrate community-based learning (CBL) in higher education (Winterbottom & Mundy, 2016). CBL is a pedagogical practice that has been outlined as student volunteerism, experiential learning, and curriculum for academic credit (Mooney & Edwards, 2001). CBL models have also incorporated problem-based service learning, direct service learning, and community-based research (Mooney & Edwards, 2001; Dallimore, Rochefort, & Simonelli, 2010).

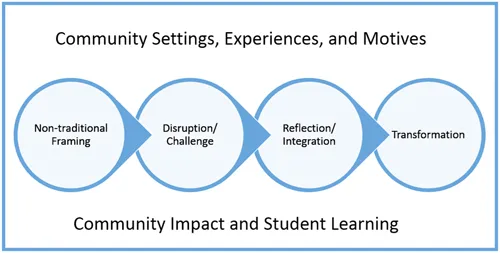

In this book, we posit that for students to have meaningful experiences at university, the CBL experiences should have transformational components integrated into the community-based activities. Figure 1.1 illustrates the approach in which community-based settings, experiences, and motives, built in reciprocal partnership with the community, lead to community impact and student learning through a transformational learning framework. The pedagogical approaches of service-learning advocacy (Mooney & Edwards, 2001), community-based research (Dallimore et al., 2010; Strand, 2000), and praxeological learning (Winterbottom & Mazzocco, 2016) could be considered synonymous with community-based transformational learning to many faculty, administrators, and students. Indeed, these activities include service learning, CBL, community engagement thinking and education, each of which has an extensive literature on its effectiveness and best practices.

Figure 1.1 The transformational pathway for students engaged in community-based transformational learning.

Components of Community-Based Transformational Learning

The foundations of CBL experiences (including service learning as well as community engagement thinking and educational practice) extend well beyond the beginning of the twentieth century (Speck & Hopp, 2004). The term “service learning” was first created in the 1970s (Sigmon, 1979) and was understood as a learning experience in which members of academia and the community receive mutual benefit. The concept that community service and volunteering in and of itself could be a learning experience dominated the early conceptions of service learning. As a way to refine the concept of service learning as an educational practice, Bringle and Hatcher (1995) defined service learning specifically as a curricular, course-based experience, where course content was connected to activities that serve the needs of the community, where students reflect on those experiences, and the experience results in an “enhanced sense of personal values and civic responsibility” (p. 112). Curricular-based service learning often is contrasted with extracurricular or cocurricular service and engagement experiences, which might not connect with course content or student learning objectives.

In this manner, models of service learning and community engagement have been varied, each emphasizing different components of community engagement connected to student learning. The often-nuanced differences among these approaches are important to researchers and experts in each perspective but may be less of a concern to those looking to facilitate community engagement for student benefits. The concept of community-based transformational learning (CBTL) broadens the reach of each of these approaches. The nuanced components of CBTL can help those researching and applying this approach to analyze how to design a successful experience, or how to tease apart why a community experience was unsuccessful in leading to desired student outcomes.

In CBTL, transformational experiences occur in authentic community-based settings. The challenges and disruptions faced by students are authentic to the community within which they are situated, and the reflection occurs either with others in the community or with community as the context for those reflections. In this book, we present many different kinds of CBL experiences and approaches; however, each chapter presents a course experience with a potential transformational learning component, connecting to the work of influential theorists in this field. Thus, the majority of the examples provided in this book are related to course-based experiences. This is not to imply that other forms of community-based and service-learning experiences cannot be transformational. Instead, we would argue that community-based experiences are transformational when they incorporate transformational elements as outlined by transformational learning theory.

Mezirow (2000) focused on experiential learning in adults, where new perspectives are gained from practical experience and reflective practice. Kiley (2005) built on Mezirow’s work to describe the transformational components of international service learning within the context of global citizenship. Freire (1970, 2000) had a distinctive community-engaged, contextual, and emancipatory perspective to this type of experiential learning, whereas Boyd and Meyers (1988) recognized the importance of integration on new perspectives into one’s personal and professional identity. We will expand upon each of these theorists, with examples from the work in this book, to convey their influence on our CBTL framework.

Mezirow (2000) identified ten stages of transformational learning; however, the transformational learning approaches can be summarized into three major components. The first component is that experiential learning involves experiences outside the classroom, and for transformational learning, the experience must be different from the traditional and typical experience of the students. These challenging experiences produce a disruption (Mezirow’s second component) in the student’s existing understanding of the world, an epistemic challenge, that the model and framework the students had prior to the transformational experience is insufficient to explain. Critical to how the students’ made sense of this disruption is the third component of Mezirow’s work, where students are able to integrate new knowledge into their existing knowledge frameworks through the process of reflection. The successful integration occurs when the level of reflection is commensurate with the level of disruption and when reflection touches on the personal or professional dimensions of identity. For example, in this book, Richard (Chapter 3) outlines the disruption of student perspectives associated with a simulation experience that asks them to experience the realities of ex-offender transition. The students reflect on how they would adjust to the challenges faced by ex-offenders if they were to transition from jail to society. The students address the personal and emotional dimensions of their experience as they empathize with the difficulties of everyday life of an ex-offender. Thus, practical experience outside the classroom, reflection, and integration produce a transformational learning experience for students.

Kiley (2005) identified transformational dimensions of service learning, which could be considered the foundation for CBTL. His model emphasized the importance of reflection to process the experience of difference, disruption, and challenge that is part of CBL environments, especially in the context of international engagement. In this book, authors, such as Winterbottom (Chapter 18), have examined student reflections on a course with a collaborative study-abroad with a university in the UK. The transformational experiences of the students included traveling and teaching in classrooms in a country with different cultural expectations. In addition, the study-abroad included an unexpected component of being in a city that had just experienced a major terrorist attack.

In contrast to Kiley’s international focus, Freire (1970, 2000) proposed an emancipatory approach to community engagement and transformational learning within the local community. His approach addressed the social structures that maintain and reinforce oppression that perpetuate challenges of the poor. For Freire, the goal of CBL is to disrupt the notions, understandings, and biases that exist because of these oppressive structures and to provide a challenging and awakening experience that leads students to social action. Kaplan (Chapter 5) provides an application of Freire’s pedagogy in which first-year college students were provided a potentially shocking experience with a local refugee population to discover their civic identity. The course was designed to provide students with an awakening experience to the plight or challenges of the refugee population and discover their civic identity and agency in empowering those individuals to address their needs. The chapter highlights that some students may not be prepared for the disruptive transformation that could result from a community experience that challenges their preconceived ideas about immigrants.

Boyd and Myers (1988) focus their transformative pedagogy on framing personal competency, emotional learning, and professional identity. In their theory, students transform through stages, with increasing awareness, personal reflection, and integration at each stage of professional and personal development. This transformative approach is more developmental and incremental than Mezirow (2000) and Freire (1970, 2000) and is reflected in Chapter 2. The authors expand upon the benefits and challenges of integrating community engagement in introductory psychology courses, applying a stage theory related to community engagement.

What is in a name? When describing CBTL, the name requires nontraditional pedagogical practices, incorporates community engagement that serves community needs, integrates reflective practice, and embraces challenging and disruptive aspects that lead students to a broader understanding of their role in the community (see Figure 1.1). Although many aspire for service learning and CBL to reach transformational outcomes, teaching practices implemented at the higher education level do not always achieve these objectives. For example, students who experience a disruptive experience in the community-based setting but who do not have structured reflection around those experiences could end up reinforcing prior stereotypes about people in the community who are different from themselves (Endres & Gould, 2009; Mitchell, Donahue, & Young-Law, 2012).

About the Book

This book was designed with multiple types of readers in mind to facilitate and ameliorate the development and refinement of CBL experiences. The book focuses on curricular community-based and service-learning experiences as opposed to cocurricular community service. In service learning, students relate community-based service experience to course objectives using structured reflection and learning activities in a regular academic course; CBL includes planning, activity, and reflection, all of which are interconnected with service learning. Some may want to learn from a chapter in a specific discipline—the book ranges from STEM-based programs (psychology, Chapters 2, 3, 4, and 14; computer science, Chapter 8; and engineering, Chapter 9) to public health disciplines (nursing, Chapter 7; physical therapy, Chapter 9) and education (Chapters 11, 14, 15, and 16). Multiple chapters present an interdisciplinary experience (Chapters 9, 10, and 15). The interdisciplinary nature of community engagement work has the potential for being transformational for students’ professional and civic identities (Hatcher, 2008; Schon, 1983). Alternatively, readers from different disciplines may be more interested in the types of experiences provided—and the experiences covered within the chapters are generalizable to many disciplines and programs. Within every chapter, readers of this book can glean information on how to design CBTL experiences, the types of community partners to use, and how to evaluate student outcomes.

E...