![]()

ONE The Sacred Right to the Elective Franchise, 1848–1861

It was a hot July Sunday in 1848. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, thirty-three years old and the busy mother of three rambunctious boys, was invited to tea at the home of Jane Hunt. Cady Stanton and Hunt lived in the twin towns of Seneca Falls and Waterloo, just off the bustling Erie Canal in upstate New York. The gathering was in honor of Lucretia Coffin Mott, in town from Philadelphia to see her sister, Martha Wright. Three other local Quaker women—Mary Ann M’Clintock and her two daughters Elizabeth and Mary Ann—joined them at the round parlor table.

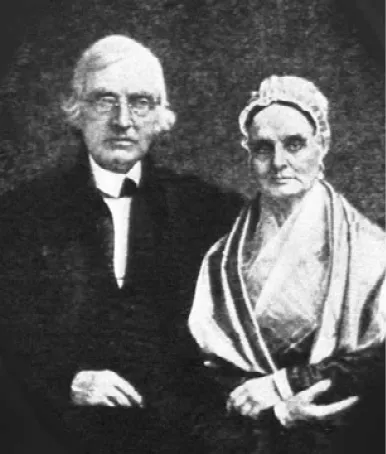

Lucretia Mott was a tiny, serene fifty-year-old whose modest Quaker dress and demeanor belied her standing as one of the most courageous, widely respected—and radical—female voices in the world of American social reform. Along with her Quaker convictions, her roots in the whaling community of Nantucket had taught her about the strength and capacities of women. Her marriage to James Mott was, by all accounts, exceptionally loving and compatible. They had five children and shared strong reform commitments, beginning with a passionate hatred of slavery. James gave up his business as a cotton trader, and their household was kept absolutely free from anything produced by slave labor. Despite Mott’s pacifist convictions, she was no stranger to violence. When a wild Philadelphia mob attacked an 1838 meeting of abolitionist women and burned the meeting hall to the ground, Mott calmly led the women outside to safety. Her reform convictions were broad. While visiting her sister in western New York, she took time to investigate the conditions and heard the concerns of nearby Seneca Indians and inmates at Auburn Prison.

That afternoon, the tea talk soon turned to a discussion about women’s wrongs. Many such discussions no doubt took place around many such tables, but this time the outcome was different. The discussion was led by Cady Stanton, recently relocated from exciting Boston to relatively sleepy Seneca Falls, her growing family and modest middle-class resources leaving her little time or energy for anything else. Her torrent of emotions was still vivid to her a half century later when she wrote her autobiography. “I suffered with mental hunger,” she wrote, “which, like an empty stomach, is very depressing.… Cleanliness, order, the love of the beautiful and artistic, all faded away in the struggle to accomplish what was absolutely necessary from hour to hour. Now I understood, as I never had before, how women could sit down and rest in the midst of general disorder.”1 Housewives from then until now would recognize themselves in her description.

Cady Stanton’s unhappiness had reached a breaking point, and finding herself surrounded by a sympathetic group of women like herself, she “poured out, that day, the torrent of my long-accumulating discontent, with such vehemence and indignation that I stirred myself, as well as the rest of the party, to do and dare anything.”2 The small group was determined to organize a “convention,” a term that had recently come into usage for public meetings to discuss and take action around compelling issues. Political parties held conventions and so did established reform movements such as temperance and antislavery. But this convention would be different; it would be the first to focus on women’s wrongs and women’s rights.

Time was short if they wanted to take advantage of Lucretia Mott’s presence, experience, and reputation. The women placed an announcement in the local paper of a two-day public meeting for protest and discussion, to be held ten days hence at the Wesleyan Chapel, a progressive religious congregation in Seneca Falls. They would discuss “the social, civil, and religious conditions and rights of women”—note the absence of “political” in the list.3 Then they began to consider what to do next, for they had few days to prepare. Only Lucretia Mott had ever planned such a public event, so they were a combination of bold and timid in calling this one. They did not sign their names to the announcement, and when it came time, none of them, not even Lucretia Mott, was willing to chair the proceedings. Writing with her characteristic verve, Cady Stanton looked back: “They were quite innocent of the herculean labors they proposed.… They felt as helpless and hopeless as if they had suddenly been asked to construct a steam engine.” But the power of the Declaration they produced belies that modest memory.

They started by drawing up a statement of principles. Instead of writing something from scratch, they decided to use as their model the Declaration of Independence, perhaps because they had just heard it a week earlier at local July 4th celebrations. We are used to hearing the Declaration of Independence cited and read often, but in the 1840s Americans had just begun to turn back to it as a powerful statement of the democratic ambitions of their still young country. What they finally produced was a bold choice, a thoroughly political statement, lacking any of the moralistic or religious flourishes expected of the “gentler” sex. And, by supplying both language and legitimacy, the Declaration of Independence also made their task easier.

They incorporated the original Preamble with a few alterations, but these were enough to make their document enduringly memorable. To the “self-evident” truth that “all men are created equal” they added the words “and women.” And instead of the “repeated injuries and usurpations… of the present King of England,” they charged the actions of “man toward woman, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny.”

Next came the grievances. Few Americans study the eighteen grievances of the 1776 Declaration, which cite imperial taxation, standing armies, impressment, and other concerns no longer relevant to us. But many of the grievances cited in the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments, the document that the women wrote, remain meaningful to this day. Marriage leaves woman man’s subordinate, obliges her to obey him, and turns her into an “irresponsible being,” unable or unwilling to be accountable for her own actions. Men have “monopolized nearly all the profitable employments,” exclude women from “the avenues to wealth and distinction” which they most prize, and provide only “scanty remuneration” for the work left. A different moral standard punishes women severely for “moral delinquencies… not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man.” The last two grievances, expansive in their reach, remain particularly powerful: that man usurps the right to define the “sphere of action” appropriate to woman; and that he does all he can “to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.” Their target was not “men” but “man” in the aggregate; they might have spoken of “patriarchy” if the word was then used that way.

Finally, the group listed thirteen powerfully worded resolutions. At the core was a grand statement of autonomy and equality: “All laws which prevent woman from occupying such a station in society as her conscience shall dictate, or which place her in a position inferior to that of man, are contrary to the great precept of nature, and therefore of no force or authority.” Once the Declaration had been drafted, Cady Stanton returned home to reflect on what the group had done. It seemed to her that something was missing. The document protested woman’s obligation to “submit to laws, in the formation of which she has had no voice,” but wasn’t this grievance the core of all the others? If so, something must be done. She resolved to call for a collective effort by women to confront women’s ultimate political powerlessness, so out of place in a democratic society. She returned the next day with a proposal for a final resolution: “that it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.”4

The right to vote eventually became the central demand of the American women’s rights movement for the next three quarters of a century, changing women’s lives and American politics in the process. In retrospect, this development might seem inevitable, that American democratic rights would eventually have to be extended across the gender divide to incorporate the omitted half of the nation’s citizens. But at the time it was voiced by that small group of women, it had rarely been expressed anywhere. During the French Revolution, radical clubs of women had demanded the right to vote, but to no avail. In the United States, only in New Jersey between 1776 and 1807 were unmarried, property-holding women able to vote. In general, women’s equal right to the franchise was a controversial and by no means obvious proposition.

An occasional advocate of women’s rights or political democracy had previously contended that women should be men’s political equals. But for the most part, the notion of women voting was considered ludicrous, counter to common sense, and beyond the limits of the democratic community. Political democracy, still a radical experiment in human government, required independent and rational citizens, and women were considered neither of these things. “Men bless their innocence are fond of representing themselves as beings of reason…,” Cady Stanton said just after the convention, “while women are mere creatures of the affections.… One would dislike to dispel the illusion, if it were possible to endure it.”5 It was widely assumed that women were an emotional, not a rational, sex, and wives were thoroughly—and properly so—dependent on their husbands. How could they be trusted to cast an intelligent vote? Often the possibility of women voting was discussed only to call into question other efforts to expand the franchise. Allow black men to vote? You might as well allow women! The absurdity of the notion was enough to shut down all discussion and leave voting rights in the hands of white men.

The convention was scheduled to begin on Wednesday, July 19, at 11 a.m. That morning the planners assembled early. Lucretia Mott came the fourteen miles from Auburn with her sister and husband. Elizabeth Cady Stanton walked less than a mile from her house on the outskirts of town to the Wesleyan Chapel, accompanied by her five-year-old son Henry Jr., her sister Harriet, and Harriet’s son Daniel. In all the difficult work that the women had done to draft their declaration, they had forgotten a small detail, to make sure that the door of the church was opened, which it wasn’t. Daniel was small enough to crawl through an open window and unlock it. Then they waited to see whether they would have an audience for their ambitious undertaking.

They did. Two-thirds of them were women, some publicly associating themselves with the convention by signing their names to its Declaration of Sentiments. Probably two or three times as many as signed actually attended. Of the hundred signers, one quarter were associated (as were the Motts) with the radical “Hicksite” wing of Quakers, and the rest were varieties of Methodists. Economically, they ranged from wealthy town-based families to farmers and their wives and daughters, who came in horse-drawn carts from villages as far as fifteen miles away. Immigration and slavery were two of the big political issues of the day, but there were no immigrants and only one second-generation young Irishwoman there. And there was one ex-slave. Ten years earlier Frederick Douglass had escaped his Maryland master. Eventually he would become one of the most famous African American men in history. In 1848, he was living and editing a weekly newspaper in nearby Rochester. He had met Elizabeth Cady Stanton seven years earlier in Boston, and each had been impressed with the other. Douglass had advertised the upcoming convention in Seneca Falls in his paper, and on the first morning he was present. Everyone else was native born, white, and Protestant.

Most of those who listened that day and the next are lost to history. But one, Charlotte Woodward Pierce, who was just eighteen at the time, lived to the age of ninety, when she was able to witness the final victory of the woman suffrage movement and to share her memories. She was one of the few working girls in the audience, though working for her meant sitting alone in her home, hand-sewing precut gloves and then returning the finished goods to the manufacturer in the aptly named village of Gloversville. “I do not believe that there was any community anywhere in which the souls of some women were not beating their wings in rebellion,” she recalled. “For my own obscure self, every fiber of my being rebelled, although silently, all the hours that I sat and sewed gloves for a miserable pittance which, after it was earned, could never be mine. I wanted to work, but I wanted to choose my task and I wanted to collect my wages.”6 She brought five friends with her, and as their wagon neared Seneca Falls they joined a large flow of traffic headed for the chapel. Charlotte Woodward Pierce was an advocate of woman suffrage through the entirety of her long life.

Although the first day of the meeting had been called for women only, Charlotte and her friends found a group of men, leaders of the village, waiting to get into the church. How to involve men had put the organizers in a bind. Women meeting in public in the company of men was still considered morally questionable, in the disturbing phrase of the period, a “promiscuous assembly.” Also the organizers expected that as difficult as it would be to get women to speak, the presence of men would make it that much more so. On the other hand, excluding men seemed to violate their most fundamental principles, that of sexual equality and individual rights. They decided on a compromise, to admit men but to allow only women to speak on the first day. Men would be able to speak—and they did so at considerable length—on the second day.

Lucretia and James Mott, c. 1842.

This last-minute small-town gathering on behalf of women’s rights was not, at the time it was held, a historic event, and there are only scant records of what actually went on during those two days. Of all the women there, only a handful dared to speak. Mott, a seasoned speaker, gave a version of remarks on “the Law of Progress,” which she had delivered at an antislavery meeting two months before. She spoke of the thrilling cascade of developments—chief of all the progress of the antislavery movement—“of ‘peace on earth, and good will to man.’ ”7 Now she added her hope that women’s rights would soon find a place in the pantheon of reform. For all her fierce convictions, Cady Stanton dared to make only some impromptu humorous remarks meant to soften any lasting impression that the convention was set against “the Lords of Creation.”8

As Cady Stanton recalled, woman suffrage was the only point on which there was any disagreement. Quakers, a large minority of the audience, found the realm of politics too corrupt, the government too sullied by its collusion with slavery, political parties too self-serving, for women to seek involvement. Others may have found it a step too far outside of woman’s traditional sphere. Even Lucretia Mott, usually unwilling to give way to conservative popular opinion, thought the notion of women’s equal political rights would “make us seem ridiculous. We must go slowly.”9 If they were not careful, they would undermine the entire women’s rights effort they were daring to initiate.

But Cady Stanton was de...