eBook - ePub

Becoming Bulletproof

Protect Yourself, Read People, Influence Situations, and Live Fearlessly

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

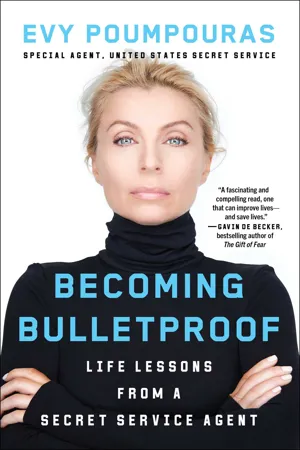

Becoming Bulletproof

Protect Yourself, Read People, Influence Situations, and Live Fearlessly

About this book

Former Secret Service agent and star of Bravo’s Spy Games Evy Poumpouras shares lessons learned from protecting presidents, as well insights and skills from the oldest and most elite security force in the world to help you prepare for stressful situations, instantly read people, influence how you are perceived, and live a more fearless life.

Becoming Bulletproof means transforming yourself into a stronger, more confident, and more powerful person. Evy Poumpouras—former Secret Service agent to three presidents and one of only five women to receive the Medal of Valor—demonstrates how we can overcome our everyday fears, have difficult conversations, know who to trust and who might not have our best interests at heart, influence situations, and prepare for the unexpected. When you have become bulletproof, you are your best, most courageous, and most powerful version of you. Poumpouras shows us that ultimately true strength is found in the mind, not the body.

Courage involves facing our fears, but it is also about resilience, grit, and having a built-in BS detector and knowing how to use it. In Becoming Bulletproof, Poumpouras demonstrates how to heighten our natural instincts to employ all these qualities and move from fear to fearlessness.

Becoming Bulletproof means transforming yourself into a stronger, more confident, and more powerful person. Evy Poumpouras—former Secret Service agent to three presidents and one of only five women to receive the Medal of Valor—demonstrates how we can overcome our everyday fears, have difficult conversations, know who to trust and who might not have our best interests at heart, influence situations, and prepare for the unexpected. When you have become bulletproof, you are your best, most courageous, and most powerful version of you. Poumpouras shows us that ultimately true strength is found in the mind, not the body.

Courage involves facing our fears, but it is also about resilience, grit, and having a built-in BS detector and knowing how to use it. In Becoming Bulletproof, Poumpouras demonstrates how to heighten our natural instincts to employ all these qualities and move from fear to fearlessness.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Becoming Bulletproof by Evy Poumpouras in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781982103774Subtopic

Business SkillsPart 1 PROTECTION

Chapter 1 How We Fear

Courage is knowing what not to fear.—PLATO

Don’t Panic!

As the cold water rushed in, I gasped for one final breath before I was completely submerged. I remember the whole cockpit tipping over, the sinking sensation in my stomach, my body straining against the harness strapping me to my seat before I hit the water sideways. My body lit up with adrenaline, ready to panic. And then everything went quiet.

I unclenched my hands and took a mental pause. Panicking would only make it harder to think, wasting valuable seconds I didn’t have. Blackness obscured my vision—there was no way to see my way to safety. If I was going to get through this, I knew I would have to feel my way out. I reached down for the release on the seat belt harness to my left… or was it my right? Was I completely upside down now? I had to be—I had lost my bearings and couldn’t find a reference point.

Don’t panic. Find the latch. Pull to release. Swim to safety.

I repeated these words as I fumbled in the dark. Damn it, where the hell was that release? My fingers finally grasped hold of the U-shaped harness lever, yanking it to the open position. As the two-inch nylon straps slowly loosened around me, I wiggled free and pulled myself through the cockpit door. I knew I had to swim clear of the cabin before making my way to the surface. My lungs were burning now, my heart pounding. A few more seconds and I would be free. I finally kicked hard and forced myself upward. As I broke through the water’s surface, I gasped for my first breath of air in what seemed like an eternity.

“Good job, Poumpouras. You didn’t drown!” shouted the Secret Service instructor. “Now get out of the pool. Next!”

The Academy training scenario for the day was a simulated helicopter crash in the Olympic-size training pool. Each recruit was first blindfolded, then strapped into the seat of a mock helicopter cockpit. The cockpit was then flipped upside down, submerging the agent, who then had to release themselves from the safety harness and swim through an underwater maze before surfacing. The training was designed to teach us how to survive should we ever find ourselves in that exact situation.

But the simulation wasn’t just a “what-if” scenario. It became part of our training after a Secret Service agent died in a real-life helicopter crash on May 26, 1973. That evening, twenty-five-year-old Special Agent J. Clifford Dietrich, along with six other agents and three Army crew members, were flying from Key Biscayne, Florida, to the Grand Cay Islands in the Bahamas for their overnight presidential protection assignment for President Nixon. Shortly before landing, the twin-engine Sikorsky VH3A helicopter crashed into the Atlantic Ocean. Although the aircraft initially remained afloat, it soon capsized, causing the cabin to quickly fill with water. While the other passengers climbed to safety on top of the overturned helicopter, Agent Dietrich never made it out.

When his body was recovered, he was found still strapped into his safety harness. According to the medical examiner, Agent Dietrich’s cause of death was asphyxia, due to drowning. Our training instructor also told us that both of the agent’s thumbs were broken. That meant Agent Dietrich had been alive and conscious when the helicopter hit the water, but ultimately drowned because he was unable to free himself from the seat belt. Under stress, the agent would have reverted to what he knew about seat belts—you push the release button with your thumbs, like in a car. But in a helicopter, the seat belt mechanism is completely different, something the agent most likely couldn’t remember in his final moments of panic.

Even though I logically knew that I probably wouldn’t die in a simulated helicopter crash, there was no way around the instinctual onset of panic that flooded through me. My mind didn’t care that this was a controlled exercise, which meant the fear of drowning was as real as anything I’d ever experienced. This exercise had nothing to do with physical strength or agility. While I was looking for a way to physically Houdini myself out of the contraption and not drown in the process, the simulation was teaching me how to maintain control of my emotions.

Fear is a healthy and natural response to a perceived threat. On the other hand, panic causes us to lose control of our faculties. When we panic, we can’t think, can’t reason, can’t process or plan. And under extreme circumstances, panic is likely to kill you faster than whatever it is you’re afraid of. If you’ve ever experienced a panic attack—heart beating rapidly, hyperventilating, trembling, feeling like you’re about to die—then you may understand what that agent felt as he hung upside down in the darkness underwater, one simple click and brief swim to his survival. He probably had minutes to assess his situation, form a plan, and escape to safety, but his panic made that impossible.

Think about car accidents. Most people, when in a car accident, will take their hands off the wheel. At a time when logic says we most need to keep our hands at ten and two, panic causes us to take our hands away from the very thing that might save us. And where do people’s hands go? Over their face. In the moments when we most need our steering wheel and our vision, panic causes us to abandon both.

This book is not about never feeling fear. It’s about understanding fear and learning to control it. I want to help you master your fear so that it doesn’t turn to panic in a moment when you need to be able to think clearly. Fear can also be a limiting influence in our lives. It can prevent us from pursuing goals that we long to go after, from speaking openly and honestly, from being who we’re truly meant to be. When we feel threatened or exposed, our fear can confine us and cut us off from the world. If that feels familiar, I’m going to help you change your relationship to fear. I’m going to show you how to get to know your fear, trust your instincts, and make choices that will keep you safe and strong.

Surviving Fear

We are born with two kinds of fears hardwired into our system for survival—two fears that scientists call innate: the fear of falling and the fear of loud sounds. Most of us have had a dream where we’re falling and then startle awake. This fear of falling has been with us since birth. Newborns are quickly wrapped in a blanket because they can’t immediately distinguish where their body ends and the world begins, which causes them to constantly jerk as if they are falling, a fear that eventually diminishes once their depth perception develops. Beyond their startle reflexes, studies show that infants refuse to crawl over a platform made of clear Plexiglas even when their mothers are at the other end calling to them. They will stop at the edge and cry rather than risk going over the “visual cliff.” Their innate fear of falling is strong enough to override even that powerful bond between mother and child.

Loud noises are the other stimulus that humans innately equate with danger. When we hear a loud noise, our acoustic startle reflex kicks in and our bodies instantly react. That’s why we jump when a car backfires, why children cry at firework shows, and why we immediately drop to the ground when we hear anything that sounds like a gunshot.

Beyond the fear of falling and the fear of loud noises, all other fears are learned fears. These are the fears that we inherit from our parents or acquire while growing up. If your mother is afraid of dogs, chances are you are going to grow up being afraid of dogs as well. Learned fears come from everywhere—our family, our friends, our culture, the news we watch, the harm we’ve witnessed or experienced. We are taught to be afraid of failing or afraid of trying at all. There is no limit to the fears we can accumulate in our lifetime.

Every generation seems to grow up with some type of societal fear. In the 1950s, it was the Red Scare and communism. The 1960s became a decade of fearing for personal safety with the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy. In the 1970s, it was the foreign oil crisis, the political upheaval with the impeachment of President Nixon, and the skyrocketing of crime throughout the United States. In the 1980s, it was the fear of external threats against the United States, particularly with Iran and the Soviet Union. In the 1990s it was the Y2K scare, fearing that all life and technology would cease once the calendar year hit 2000. The early 2000s ushered in a global threat unlike anything before it—terrorism.

Today we have mass shootings. A 2018 Pew Research Center study found that more than 50 percent of teenagers were concerned that a shooting would happen in their school, with 25 percent of them being “very worried.” This fear persists despite the statistical improbability of any one student becoming a school-shooting victim. With more than 50 million American youths attending public K–12 schools for roughly 180 days of the year, the chance of being killed by a school shooter is about 1 in 614 million. By contrast, the likelihood of being struck by lightning in any one year is 1 in 1.2 million. Highlighting this mathematical implausibility, however, usually won’t diminish the worry of students or their parents, any more than it would diminish the fear of being attacked and killed by a shark (1 in 3.7 million) or being in an airline crash (1 in 5.4 million).

The debilitating nature of any fear, especially unlikely ones, can drastically limit our ability to simply enjoy life. These fears can make some people too afraid to board a plane or swim in the ocean. Perhaps those people would be willing to drive to the beach, so long as they don’t wade into the water past their knees, or take a long road trip rather than take the risk of flying. They might choose these deceptively “safer” options despite the fact that there is a far greater chance of being injured in a car crash than a shark attack or plane crash. In fact, there is a 1 in 102 chance that you could be killed in a car accident in a given year.

So why aren’t people more afraid of dangers with a higher statistical probability, like car accidents? Why do we become so preoccupied with threats that have an incredibly low chance of ever occurring? Our fears have to do with several things, the first of which is the sensationalizing nature of the incidents by the media. When things that rarely happen, happen, they become newsworthy. You are more likely to see, and thus remember, the social media post or evening news story about the victim of an unlikely tragedy—a surfer attacked by a great white shark off the coast of California—than you are about the two-vehicle accident that sent one driver to the hospital, something so common it likely won’t even make the news. Exposure to those kinds of stories make those unlikely threats feel more real to us, and that fear overrides our ability to logically assess the probability of those things actually happening.

Additionally, we are genetically predisposed to avoid things that can cause instant death—a big fish with teeth, a 1,000-volt bolt of lightning, or falling out of the sky. My intent here is not to make you more afraid of driving, but to get you to reflect on those things that you are most fearful of, to assess why you are afraid of them, and look at them logically, rather than enduring a clouded sense of dread amplified by sensationalized stories.

What Fear Looks Like

When I was sixteen, my family and I moved from Long Island City into a better neighborhood in Queens. Although crime in that part of New York wasn’t nonexistent, it wasn’t nearly as bad as where we came from. Because money was always tight, my little brother, Theodoros, and I helped our parents clean office buildings on the weekends after they each finished their day jobs. One Sunday night, after finishing early, my mom and I drove back to our house while my father and brother stayed a few minutes longer to lock up.

When we pulled into our driveway, I noticed the vertical blinds in the living room were open and the lights were on.

“Why are the lights on?” I asked my mom. “And the blinds open?”

She looked confused. “I don’t know. We always close them.”

We didn’t completely register that something was amiss until my mom unlocked the front door and we walked in. And that’s when I saw him—a man running through our house toward the side entrance.

My mom immediately froze—literally went motionless, as if her feet were cemented into the floor. I, on the other hand, didn’t hesitate—I charged inside.

“No!” my mom screamed. “Stop!” But she wasn’t yelling at the intruder. She was yelling at me. I was already running after him. When I got to the side door, I saw him leap over the neighbor’s fence and into the black of night. Gone.

“Maybe there are others still here!” I shouted back to her and began checking every room in the house.

“No,” my mom pleaded. “Stop, just stop.”

She was terrified for me, but her cries somehow sounded far off in the distance. I was mad going on furious as I first cleared the basement and then worked my way back upstairs. I was going to protect my mom, protect our home, no matter what. I may have only been a teenager, but God help whoever was still in this house. I didn’t know how, but I was not going to let them get away until the police arrived and took them to jail.

Now, at this point in the story you might be thinking Wow, you’ve got some balls!, or maybe Listen to your mother, you idiot. You’re gonna get yourself killed.

Regardless of what you’re thinking about my level of bravery—or stupidity—I share this story with you for an entirely different reason. First, let’s go back to the start of the story: we pulled up to the house together in the car and immediately knew something was wrong. Our sense of fear and uncertainty began to build. When we walked inside, we saw a man running through our house. Fear built faster alongside the slightly delayed recognition that we were being burglarized. Now what happened? What did my mom do? What did I do? My mom froze in her tracks. I ran after the guy. Bravery? Hardly.

My mom and I experienced the exact same exposure to a threat, yet we had two completely different reactions. These reactions are called our Fight, Flight, or Freeze responses, also known as the F3 response. My mom went into Freeze mode, whereas I went into Fight mode. And you could argue that the intruder I was chasing was in Flight mode.

Researchers say our Fight, Flight, or Freeze response activates even before we are aware of it as a way of assessing danger. If it’s a threat we think we can overpower, we go into Fight mode. If it’s a threat we think we can outrun, we go into Flight mode. If it’s a threat where we think we can do neither—we Freeze. People may have a different response to the same stimuli—as my mother and I did—but no matter what your particular response to fear may be, the most important thing is to know and understand it so you can control it.

Fight, Flight, or Freeze

F3 is your body’s way of arming itself to help protect you. It is your physiological response to help you deal with the situation at hand. It’s you—but a heightened version of you. A more aware and alert version. Your heartbeat increases so as to pump more blood throughout your body, which will make it easier to punch someone (Fight) or run away (Flight).

For people like myself who naturally go into Fight mode when faced with a threat, our natural instinct is to immediately combat whatever is threatening us—whether or not it is safe to do so. If someone hits you, you hit back. If someone yells at you, you yell back. It’s a response in which you retaliate with an aggressive behavior to protect yourself. You make the decision to take a defensive stance against the threat, whoever or ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Prologue

- Introduction: Harder to Stop

- Part 1: Protection

- Part 2: Reading People

- Part 3: Influence

- Conclusion: Becoming Bulletproof

- Afterword: Fear and Courage

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Index

- Copyright