![]()

Chapter 1

1850–1890

The Dawn of Modern Clothing

Fashion in the period 1850–1890 reflected the latest developments in engineering, chemistry, and communications. During the second half of the 19th century, the growth of photography and inventions such as aniline dye and the sewing machine all had impact on the design, manufacture, and distribution of clothing. This period witnessed the development of the “fashion designer” as a profession, and the birth of the haute couture system. Family businesses dominated the fashion world. Worth, Creed, Redfern, and Doucet were all dynasties that lasted through several generations. International politics and social and economic fluctuations strongly affected fashion as well; changes in government and trade relations, urbanism, and increased social mobility all influenced dress. Visitors to any of the international expositions of the 1850s – including the Great Exhibition in London’s “Crystal Palace” in 1851, the subsequent Great Exhibition in New York in 1853, or the Exposition Universelle of 1855 in Paris – could not have failed to notice that the world of material pleasures was rapidly expanding.

By the 1850s the use of sewing machines in the commercial manufacture of clothing was widespread, and models for home use, as shown here, were widely marketed as well.

The Road to 1850

By the late 18th century the phenomenon of fashion had developed into a progression of silhouettes that typically evolved from the previous style; these silhouettes began to change at a faster rate than ever before in the history of fashion. Style setters such as Queen Marie Antoinette of France and George, the English Prince Regent, wore fashions that were quickly copied by others. Subsets of fashionable people devoted to a particular look were well established, and popular culture influenced clothing as the stylish imitated famous performers and fictional characters. Colored fashion plates were significant to the development of a fashion press.

From the beginning of the 19th century historicism and orientalism were recurrent themes in fashion and the arts. Influences from India and Central Asia were popular, and styles of the past (including the Middle Ages, the Elizabethan era, and the 17th century) were revived. The lure of the exotic and of the past were by-products of the prevailing artistic movement, Romanticism. Fashion leaders for women included Joséphine Bonaparte, Empress of France, and Dolley Madison, wife of the American president. Men’s fashion was dominated by two personalities and their contrasting points of view: George Bryan “Beau” Brummell was known for tailored restraint, while Lord Byron advocated a poetically disheveled look. The progression of styles for men and women produced periodic undulations in skirt shapes and lengths, necklines, sleeves, waists, shoulders, and cravats.

1837 saw the beginning of the sixty-three-year reign of Queen Victoria, the most powerful and influential monarch in Europe, who set social standards until her death in 1901. For her marriage to her cousin, Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, on February 10, 1840, Victoria chose a white wedding dress and orange blossoms, solidifying an important dress custom. Victoria’s emphasis on conservative social values represented a pendulum swing from the permissive society of the Regency period in Britain. The impact of the Industrial Revolution, and economic depressions in parts of the world (including Australia and the United States) were reflected in clothing of the 1840s. Silhouettes for both men and women became simpler, and decoration and colors became more subdued. Modesty was a priority and sartorial sobriety was typical, especially in the United Kingdom and the United States.

During the 1840s, women’s clothing was characterized by a jewel neckline and long sleeves. Sleeves were commonly simple and straight; as the decade progressed bodices sometimes had flared sleeves, with cotton or linen undersleeves, usually with a matching collar. Décolletage was seen in women’s eveningwear, but was most often in the form of a wide bateau neckline and seldom showed cleavage. Skirts became longer, usually reaching the floor, after shorter lengths had been popular in the 1830s, and petticoats maintained a bell-shaped silhouette. The waist was slightly dropped and bodices typically came down to a center front point. The poke bonnet was the dominant hat style and its closely fitted sides and brim were in keeping with the prevailing focus on modesty.

Men typically wore the frock coat; trousers were straight with fly fronts. Colors were dark and somber. For formal wear (outside of court dress), black tailcoats were the standard of elegance, sometimes still worn with knee breeches although long pants began to be common in the evening as well. The top hat was the most widespread hat style.

Social and Economic Background

In Britain, under the long rule of Queen Victoria, industrialization continued at a rapid pace. The development of railroads, the migration of workers into cities, and the expansion of colonial influence in China, Africa, Southeast Asia, and India all contributed to the prosperity and self-image of the British and were important to evolutions in taste. The scope of the British Empire was reflected in the availability of goods from all over the world and the adoption of particular items of dress. By the mid-19th century Paris was the undisputed center of fashion despite the turbulent state of French politics.

An illustration from American Fashions from 1847 depicts a family in styles typical of the mid-19th century.

The Second Empire began in 1852 when President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte proclaimed himself Emperor Napoleon III. Members of the French court, especially Napoleon’s attractive wife, Empress Eugénie, were influential in matters of style. Other European royals, including Elisabeth, Empress of Austria, and Princess Pauline Metternich, the wife of the Austrian ambassador to the French court, were also fashion leaders. However, the aristocracy vied with new fortunes made in finance, real estate, transportation, and manufacturing. Royals, aristocrats, and nouveaux riches all took part in the spectacle of fashionable life in Paris, which was transformed into a modern city of wide boulevards and impressive open spaces. Following the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 the Second Empire came to an end, and by 1872 the Third Republic was in place. Elsewhere in Europe, following a series of upheavals in 1848, the various small kingdoms of Germany were consolidated under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. In Italy, the Third War of Independence in 1866 made Giuseppe Garibaldi a national hero.

Other parts of the world experienced similar disruptions. Changes in international relations affected technological developments and trade. The American Civil War (1861–1865), and the abolition of slavery, had a significant impact on the American economy, westward expansion, and the textile industry. During the war, the mobilization of over three million servicemen necessitated the mass production of clothing and led to the beginnings of industry sizing standards. In addition, profits generated by the war helped establish a new class of wealthy industrialists. Unable to import cotton from America during the Civil War, Britain turned to Australian sources, giving a boost to cotton production in the colony.

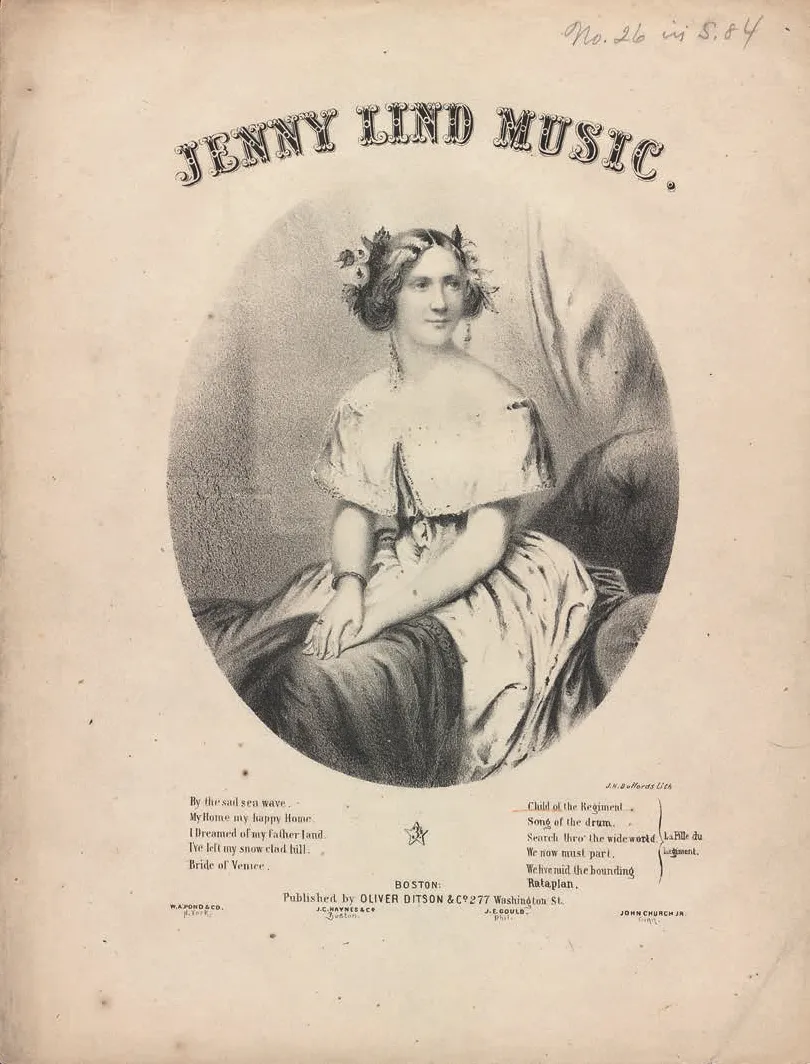

JENNY LIND

Swedish soprano Johanna Maria “Jenny” Lind (1820–1887) was known for her concert performances in Europe during the 1840s and the United States during the early 1850s, the latter produced by flamboyant circus promoter P. T. Barnum. Lind was contracted for previously unheard-of fees. Barnum orchestrated remarkable advance publicity and succeeded in creating a cult figure playing to sold-out houses on her American tour. The “Lindomania” (or “Jenny Rage”) caused by her American popularity led to frantic audiences and rioting in oversold concert halls. One night when Lind’s veil fell off the stage and into the audience “it was ripped to shreds by relic hunters.”1 Jenny Lind’s style was widely imitated by fashionable women, and some fashion historians have even credited her with popularizing the style for the three-tiered skirt of the early 1850s. The media circus surrounding Lind, her rabid fan base, and the official souvenir merchandise were unprecedented for a musician, anticipated only by the enthusiasm that had surrounded pianist Franz Liszt in Europe the decade before. Lind’s career is especially important as a prototype for pop culture iconography, and the extent of this extreme musical fandom and hype foreshadows the “Beatlemania” of the 1960s and other similar 20th-century phenomena.

An album of “Jenny Lind Music,” c. 1850, published in Boston.

In one of the most significant global events of the 19th century, Japan opened its borders in 1853–1854. The end of more than 250 years of isolation led to new diplomatic missions and had a notable impact on Western tastes. Trade treaties were signed with the United States, followed by other major countries, and several Japanese port cities became open to trade. Japanese goods entered the Western market.

The Arts

While this period was marked by a spirit of experimentation – even rebellion – in the arts, historicism and orientalism continued to be major factors in art and design. The Académie des Beaux-Arts of Paris and the Royal Academy of Arts in London promoted history painting as the most important genre, while depictions of contemporary life were considered the lowest level of endeavor. In a gesture of independence from the academy, the Impressionist movement officially began in Paris in 1874 with an exhibition organized by the Anonymous Society of Artists, whose members included Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Gustave Caillebotte, and Berthe Morisot. Taking their subject matter from the world around them, these artists created scenes of boating parties, people at the beach, vibrant views of the countryside, and images of the movement and sparkle of life in their fast-paced world. Just as synthetic dyes made mid-century fashions brighter, new chemical pigments became available for artists who exploited spectacular new hues. Fashion was integral to modern life and the Impressionists captured stylish men and women at sun-dappled picnics, cafes, theaters, and racetracks.

Romantic artists such as Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérôme perpetuated a romanticized view of Asia as well as Egypt and North Africa. Performing arts contributed to the orientalist vogue. In 1871 Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi created his idealized version of ancient Egypt in Aida. The Parisian taste for theatrical excess was whetted by Jules Massenet, who took audiences to South Asia with Le Roi de Lahore (1877) and to Byzantium with Esclarmonde (1889). Giacomo Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine (1865) and Léo Delibes’ Lakmé (1883) depicted forbidden love between European men and Eastern women. Ballet also contributed to the trend of orientalist entertainments: among many such productions, Cesare Pugni’s The Pharaoh’s Daughter (1862) was particularly ludicrous, involving opium-induced hallucinations and reanimated mummies.

Portrait photography became increasingly popular not just among the wealthy but also among the growing middle class. Celebrities such as the Countess di Castiglione and Lillie Langtry understood the power of photography as a means of manipulating public image. French photographers such as Nadar chronicled the age, while Julia Margaret Cameron captured the Aesthetic dress of the British intelligentsia. Even ordinary citizens posed for their local photographer and the resulting cartes de visite, portraits, and group photos record the enthusiasm for this new medium.

The Fruits of Industry

While a rigid social hierarchy was still in place in Europe, North America experienced greater social mobility. In the United States, only one hundred years old in 1876, social position was increasingly determined by wealth, rather than birth. Though descended from Dutch farmers in colonial New York, the Vanderbilts established themselves as leaders of New York society. Likewise, the Astors, originally a merchant family from Germany, created an important real estate empire. These prominent families constituted a sort of American equivalent to Old World aristocracy. The Astors, Vanderbilts, and other prominent New Yorkers such as J. P. Morgan were instrumental in the founding of major cultural institutions. Throughout North America fashion leaders emerged from fortunes made in a great variety of industries; they were important to Paris fashion. Isabella Stewart Gardner of Boston was the heiress to a textile and mining fortune. Chicago society followed Mrs. Cyrus (Nettie) McCormick, whose husband invented a mechanical reaper, and Bertha Honoré Palmer, wealthy from her husband’s real estate empire. Potter Palmer founded a dry goods store, Potter Palmer and Co., that became retail giant Marshall Field & Co. American millionaires married their heavily dowered daughters into aristocratic European families. Titles ennobled the sometimes ill-gotten gains of the wealthy “Robber Baron” families and American “Dollar Princesses” brought much needed capital to impoverished aristocrats.

Industrialization also contributed to the growth of cities and an urban middle class. Improvements in production methods led to an unprecedented choice of consumer goods. The first practical sewing machine came from Elias Howe (1819–1867). Howe received a patent in 1846 and steadily improved his model. When Howe’s competitor John Bachelder sold his patent to I. M. Singer (1811–1875) in the early 1850s, the machine had been improved to the point where Singer could successfully modify and actively market it. Commercial models were in use during the 1850s and the first Singer model for the hom...