![]()

CHAPTER ONE

YOU ARE NOT A LOAN:

RECOGNIZING OUR POWER IN THE AGE OF DEBT

Most people are not in debt because they live beyond their means; they are in debt because they have been denied the means to live.

The fact that employers refuse to provide living wages enables creditors to loan more money, with interest, to desperate workers. In this sense, our bosses and lenders collude to rob us twice: first, by underpaying us, and then by charging us interest to borrow the money we need to make ends meet.

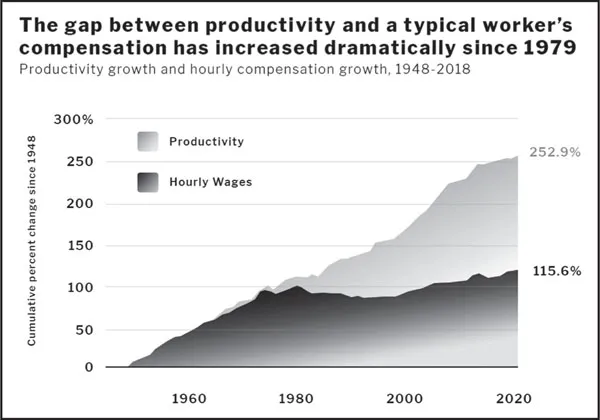

Look at this graph illustrating the relationship between productivity and wages.

Since World War II the wealth we produce has been going up and up and up, but our wages have remained stagnant since the mid-1970s. Although we are working longer hours, a growing number of us are forced to cobble together multiple jobs and side hustles. While our work is producing more wealth than ever before, that wealth is being captured by the 1 percent. The pie has been getting bigger, but our slice has stayed the same or shrunk. A full eight out of every ten dollars we produce goes into the pockets of the richest 1 percent.

The Coronavirus pandemic revealed just how out of touch elites are when it comes to most people’s household budgets. In the spring of 2020, after millions had lost their jobs and food banks were feeding record numbers of people, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi appeared on a late night comedy show to joke about how much gourmet ice cream she had stored in one of her two freezers. That same week, treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin appeared on cable news to tout the Trump administration’s “stimulus” package, consisting largely of one-time $1,200 payments to individuals. In a “let them eat cake” moment for the ages, Mnuchin said he believed the package would “provide economic relief for about ten weeks.” He failed to mention that the US Treasury made it legal for banks to seize those meager checks for outstanding debts.

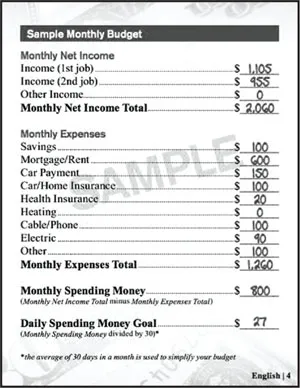

Our lives cannot be improved by following the glib prescriptions that have long come from on high. Consider the sample budget created by financial advisors at the Visa credit card company for McDonald’s employees, which claimed to show how it was possible to live on a fast-food worker’s income.

The first thing to notice is that they immediately concede that living on a McDonald’s salary can’t be done. The budget requires a second job that pays almost as much as the primary one. No worries, they seem to be saying, you’ll sleep when you’re dead! Some of the budget lines are impossible flights of fancy, like monthly rent of $600 a month, something less likely in many major cities than finding a unicorn. Even more absurd, the budget allows $0 for heat and it doesn’t mention food. It seems being responsible means freezing and not eating.

Visa’s guidelines demonstrate why the advice of experts who preach financial “literacy” and “responsibility” is so insidious. To personal finance gurus, whose existence is dependent on not criticizing the rules of the game, being a good person means working multiple jobs, taking on debt to fill the gaps, and never questioning the arrangement. They want you to work and to be as obedient and profitable to bosses and creditors as possible.

THE MYTH OF THE “GOOD”DEBTOR

Our economy is built on lies. We are told that debt offers an opportunity to get ahead when, in reality, most people spend their entire lives stuck on the debt treadmill. Take out student loans to go to college so you can graduate and get a good job; borrow money so you can build your credit score and buy more stuff; take out a mortgage so you can become a homeowner; become an entrepreneur with a small business loan. Debt is presented as a crucial rung on the ladder to a better life, a stepping stone to the American dream. If we can’t dig our way out of these “good” debts, we are to blame. But the fact is that most people can’t dig themselves out—three-quarters of people take their debts to the grave. On average, Americans die holding $62,000 of debt.

The capitalist fable of upward mobility has always been an illusion. While leveraging debt has lifted some out of poverty (access to credit was a cornerstone of policies that helped create the white middle class), the majority has been left behind or pushed into predatory contracts they can never escape. Debt, however, is more than a trap. It’s a form of social control. To give just one example, in 2019 the US Army actually admitted that they exceed their recruiting goals by targeting students in debt. As army recruiting Command Major General Frank Muth put it, “One of the national crises right now is student loans, so $31,000 is [about] the average. […] You can get out [of the Army] after four years, 100 percent paid for state college anywhere in the United States.” To be indebted makes us vulnerable to predators of all kinds, including predatory lenders, predatory debt collectors, and predatory military recruiters.

In myriad ways, debt erodes our freedom and forces unbearable choices on us: should I pay my mortgage or pay for my chemotherapy? Should I take out loans to pay for college or enlist in the army to get financial aid? Should I put the groceries on a credit card or be late with rent? Should I go to a payday lender or sleep in my car? We internalize the narrative that we have taken on debt freely and the burden is ours alone to bear when nothing could be further from the truth.

To be indebted is typically a shameful experience. We are hounded by collectors via telephone and mail, our credit scores plummet, and, along with them, our chances for housing, loans, and even employment. Our self-esteem, self-worth, and physical and mental health take a dive too. Being indebted weighs on the body and the mind, stressing us out and making us ill. That’s not an accident.

A loan is a weapon for making us feel powerless. Mortgages are a good example. In 1914 Ford Motor Company embarked on a new experiment that gave it nearly dictatorial power over its workers. Henry Ford created his own secret police force and gave it the Orwellian name “Ford Sociological Department.” The job of this department was to spy intrusively on factory workers and their families to make sure they were sufficiently conforming to Ford’s ideas about the American way of life. This meant an emphasis on thrift and upright moral living (no gambling and certainly no political agitating). Among other things, they wanted to know how much money each worker had saved, in which banks, how much debt they owed, and to whom.

The investigators especially discouraged renting out rooms, even to recent immigrants who were also working at Ford, and pressured employees to buy their own homes and helped them find a mortgage. Why would they care about this? What difference did it matter to management if their employees rented or owned a home? First, they discouraged taking on boarders because, despite the gospel of thrift, they didn’t want the workers to have additional sources of revenue. They wanted workers to be completely dependent on the income from their factory job. They also discouraged workers’ wives from working for money, both to serve the ideal of a lone male breadwinner and to make the entire household dependent on a single factory income. Second, forcing people into mortgages made them docile workers, unlikely to join a labor strike or cause trouble because doing so might jeopardize their ability to pay their mortgage. Anyone who didn’t conform to the Ford Sociological Department’s strict standards could have their pay docked and be placed on probation until they “turned their lives around,” or they could be fired outright if they resisted this control over their daily lives. Mortgage debt meant that Ford could take away more than just workers’ jobs—he could threaten their shelter, too.

Today our privatized healthcare system serves a similar function, even if it is less explicit. Linking medical coverage to employment keeps workers docile and forces unions to spend more of their resources fighting for adequate and affordable health care instead of higher pay, shorter shifts, and real worker ownership of businesses. Many people are tethered to jobs they despise and can’t leave because they need the privatized insurance accessed through their employer. After all, one thing worse than a job you hate may be not having one, especially if you have a pre-existing condition that puts your life at risk. Everyone knows that if you are not insured, a single accident can lead to a mountain of hospital bills. More than a third of Americans have medical debt.

When COVID-19 hit, people weren’t just afraid of contracting a deadly illness—they were also afraid of losing their jobs along with their insurance, and tens of millions did overnight. In the months before the outbreak, centrist Democrats and their allies worked hard to attack universal health care. For example, in early February 2020, the leadership of the Culinary Union, which represents casino workers, came out against Medicare for All, arguing that it would cause their membership to lose their private insurance. (In the end membership bucked their leaders and voted overwhelmingly for senator Bernie Sanders, who supported Medicare for All.) One month later the casinos were shut down by the crisis. Even though these casinos got a hefty bailout, more than sixty thousand culinary workers were out of a job and without health care coverage. The pandemic put the pathologies of the American employer-driven, for-profit, debt-producing system of private insurance on display for all to see. In response to the global crisis, industry analysts predicted that health care premiums were set to rise by 40 percent, ensuring ever more people will pay for medical treatment with credit cards.

Debt, in this sense, is a kind of cover-up. Our private contracts, and our desperate attempts to be “good” debtors, all work to conceal a larger crime: the crime of treating health care, shelter, and education as profit centers. Think about the idealistic young student who wants to become a lawyer so they can fight for justice and protect those who have been harmed. By the time they get out of law school, they are looking at six figures of student debt. They could become a public defender—or they could enter corporate law. A corporate law salary allows them a path to pay off their loans. Suddenly the whole reason they wanted to study law in the first place has been replaced with its polar opposite. Eighty percent of Harvard Law School students, to use just one example, enter law school saying they want to practice public interest law. Yet, upon graduation, 80 percent of them go on to practice corporate law. (“But there’s a Public Service Loan Forgiveness program to address just this problem!” you might say. To date, the government has denied more than 99 percent of those who have applied to get their loans discharged through this program.)

This isn’t just the brainwashing of the Ivy League—although there certainly is a fair amount of that, too—this is the disciplinary function of debt. Most of us want to be better people than we are allowed to be. We are forced to do things we are ethically opposed to, just to survive. We have to service our loans instead of serving the greater good.

FROM DIVESTMENT TO DEBT

The myth of the debtor as an individual who made a bad choice obscures the reason that we are in debt. Medical debt doesn’t exist in countries with nationalized health care systems, and student debt is unheard of in parts of the world where public college is free. In the US, the problem is public disinvestment, or what is often called “austerity.” Millions who should be eligible for Medicaid, for example, have been pushed off the rolls in recent years. According to one analysis, the number of uninsured children in the US rose by more than four hundred thousand between 2016 and 2018. Disinvestment in the things people need to survive and thrive opens space for profit-hungry predators. In the midst of the Coronavirus outbreak, the public was shocked to learn that some hospitals were laying off hospital workers and cutting staff salaries while price-gouging patients. Why? Because the hospitals had been acquired by private equity firms, which are in the business of buying companies in order to “restructure” them. For investors, the emergency rooms were not vital public resources but simply cash machines.

Public higher education has also been damaged by “austerity.” Public college was free or low cost for much of the twentieth century, and student debt was too insignificant to measure until the 1990s. Things began to unravel in the 1970s, when more people, particularly Black and brown people, demanded access to educational opportunities. In response, states started reducing subsidies to public colleges, and elected officials began talking about public education as a private benefit. A main architect of this shift was California governor Ronald Reagan, who declared war on students at the University of California, whom he called “beatniks, radicals, and filthy speech advocates.” He sent in the National Guard to put a stop to student protests and insisted that raising tuition was necessary to quell dissent. Since then, state revenue at public institutions has cratered. Subsidies to schools like Michigan State, the University of Illinois, and the University of California at Berkeley were reduced by more than half between 1987 and 2012. The University of California as a whole now receives only 9 percent of its budget from the state, a massive, decades-long disinvestment campaign that has caused tuition to skyrocket.

Decades of disinvestment in public education has opened up space for predatory for-profit colleges, which are notorious for preying on low-income students, people of color, first-generation students, veterans, and single mothers. Promising a better future, these companies do little more than load students up with loans in order to line the pockets of executives and shareholders.

In area after area, what should be public goods are financed by private debt, with disastrous consequences. Invisible webs of debt wrap around every asset and siphon value from every exchange, allowing the richest among us to profit from the relative poverty of others. Never forget: your debt is someone else’s asset. Bits of our student loan, mortgage, credit card, and auto loan payments are pooled in order to make money for investors around the world. Bundled with the debt of others, your promise to repay is bought and sold, sliced and diced and speculated on.

And yet we are still sold the lie that debt is a moral relationship between a single creditor and a single debtor. In reality, when a bill collector calls and harasses you, they are probably working for a company that bought your debt for pennies on the dollar from a debt broker. Vultures preying on you to make a buck, they are often willing to break the law to do so. The vast majority of collectors lack the basic paperwork they need to collect legally, yet they issue threats, take people to court, and sometimes land debtors in jail.

Debtors are not just in the red, we’re in the dark. This is one important problem that debtors’ unions can address. Many debtors don’t know who profits when they pay their debts, or who stands to lose if they don’t. Creditors don’t want us to understand our debts, which is why we’re always told that finance is too complex for regular people to understand. The powerful don’t want their schemes to be exposed.

We’re in the dark in another sense. Debtors don’t know one another. We are isolated and kept apart. Unlike workers organized in a labor union, where a workplace provides a common meeting place, debtors are dispersed far and wide. This is another challenge debtors’ unions must overcome— helping people who are being taken advantage of by common creditors to find each other, so we can fight back together instead of being picked off one by one.

Historically, credit means trust—the act of letting someone borrow resources with the good faith they’ll pay you back later when their circumstances have improved. But today, credit is not about trust; it’s about extraction. It is hard to overstate just how fundamental trust is to being human. Even the financial terminology hints at this. A financial “trust” is, underneath it all, about real trust. Debtor organizing and debt strikes, just like labor strikes, require building a different kind of trust in one another.

To be clear, relationships of credit and debt are not essentially evil. In fact, debt and credit can and should expand the possibilities of the present, allowing households and communities to access the goods and services they need to thrive. Imagine a city or state borrowing from public banks, not Wall Street, to build infrastructure, such as high-speed trains or schools, so residents can live better in the long term. Too often, though, debt limits our prospects, binding us in chains of compound interest. We mortgage our individual lives for the chance of making it through the day instead of enriching our collective future.

THE TIE THAT BINDS

Disinvestment in public health and welfare has deadly consequences. When people don’t earn enough money to care for their families, when they lack access to quality health care, education and other resources, they seek relief any way they can. Drug and alcohol addiction have seen a precipitous rise in recent years, resulting in an increase in what authors Ann Case and Angus Deaton called “deaths of despair.” In 2017 alone the number of such deaths totaled 158,000. “The equivalent,” the authors wrote, “of three full 737 MAXs falling out of the sky every day, with no survivors.” Suicide rates have also exploded, increasing every year for the last thirteen years. Unsurprisingly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned that working-class people were at highest risk of premature death. In 2016, a landmark study showed that the richest American men now live an average of fifteen years longer than the poorest 1 percent of the population.

Though some are better off than others, economic insecurity and its attendant physical and psychic costs are cross-class phenomena. The fear of being laid off or of being unable to access health care when you need it impacts people higher up the income ladder, too, sparing only the truly affluent. Even those who have a financial cushion—a decent salary and maybe some savings or family support to fall back on— are increasingly aware that their own livelihoods are precarious and may be snatched away in an instant, as we saw when the Coronavirus pandemic swept the country.

Many professionals who could formerly count on a decent, secure standard of living have seen their fields decimated. College degree holders are supposed to be insulated from economic downturns. But in recent years, they have felt the squeeze. According to the Economic Policy Institute, some graduates now earn lower wages than they did ten years ago. Anyone who tells you that a co...