This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

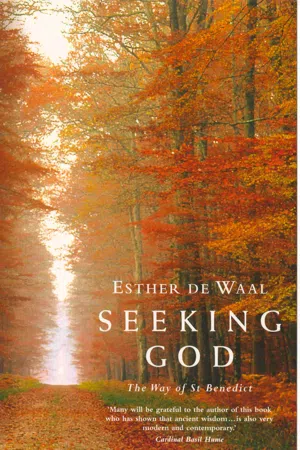

A new edition of this contemporary spirtitual classic in which the ancient and gentle wisdom of the Rule of St Benedict is explored in realtion to the demands of modern living and the importance of balance between prayer, work and study.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Seeking God by Esther De Waal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

IX

AUTHORITY

‘the utmost care and concern’

‘Advice from a Father who loves you’, a phrase in the second sentence of the Rule, follows immediately the opening sentence ‘Listen carefully, my son, to the master’s instructions’ and qualifies it. The juxtaposition of the two is significant; it sets the scene from the start. Here is authority of a master exercised with the loving solicitude of a father. So the first thing that defines the abbot is not his position at the head of an institution but his relationship with sons. The way in which this was lost in the Middle Ages when the abbot became less and less the loving father and more and more the wealthy, industrious prelate, administrator and public figure, only helps to make the point that this type of leadership demands constant watching if it is not to become institutionalized, the structure taking precedence over people. But this is not the pater familias of the later Roman society, the role which gave the head of his household control over his slaves and children to the point of life and death. To see it in terms of a patriarchal relationship is to miss much that is sensitive, and we today, as we question the Victorian father-figure and yet cannot find a wholly adequate alternative, are well placed to appreciate this. But the fullness of the portrait can only really emerge when we add to it the other titles which the Rule gives to the abbot, master and shepherd, and when we see how he also exercises the functions of doctor and administrator. There is gentleness here but there is also firmness. This man who will so often be exercising mercy towards those under him must know that it is not always in the best interests of either individual or community to fail to reprove or to say enough is enough. Those who challenge his authority need to know how far they can go; without that there is no security, and growth into responsible maturity needs that security – as parents know. If I am too much of a permissive mother there is a point at which I may do my children an active dis-service by not taking a firm stand or giving them a framework to family life which asks of them that they observe certain limitations.

What St Benedict expects from his abbot, as from his monks, is obedience, listening to the Word, to the Rule, to the brothers. So from the first his power is curtailed, for no dictator can emerge from a person earthed in the demands made by true obedience. But more than this, the abbot reflects Christ whose place he holds, the Christ who throughout the Prologue was offering the ‘way of life’. The love that he expresses is the love of Christ; the teaching that he is to deliver is the teaching of Christ himself. So what does it mean when the abbot is a teacher and the monastery a school? The best analogy is of a father teaching his children or a master his apprentices. The term ‘school’ as it is used in ‘school of the Lord’s service’ is misleading if it carries any suggestion of formal education. Originally the word was used for a room or a hall in which people assembled for a common purpose, and in the Rule its usage means a group who have come together for the common purpose of seeking God. So it is both a place and a human group. But the learning process is more analogous to that of apprenticeship by which one person learns a skill from another. In the ancient world, skills were handed down from father to son, and so apprenticeship also carries with it the implication of a father-son relationship. It involves imitation, and long, patient watching and copying, a shared learning that owes much to the fact of daily living together.

Then St Benedict introduces another subtle hint, showing a delicacy about education and learning that is far more sensitive than much that is practised in schools and colleges today. The abbot’s guidance and teaching has to be introduced almost imperceptibly into the minds of the disciples, almost like leaven, so that they think they have taught it themselves (2.5). He uses an example which makes the point vividly to those who are today again making their own bread and thus familiar with that mysterious action of the yeast, first breaking into life itself and then animating that dull mass of flour until it is transformed and becomes something quite other, while still remaining in essence the same material.

This is not theoretical knowledge but practical knowledge of how to live, not formal and structured but given through personal contact, often in subtle ways. So the abbot’s primary qualification is not intellectual or academic but ‘goodness of life and wisdom in teaching’ (64.2). He communicates by word and by deed, but even more by example; the message of his own life is more effective than what he says. St Benedict clearly thinks little of dry theological speculation and academic knowledge acquired through books, and in this, as so often, he reveals his firm grasp on reality. Ask anyone what really brought them to the Christian faith and enabled them to live and grow in it, and it is unlikely that they will say ‘intellectual understanding’. It is more probable that their answer will be either some person whose way of life proved an inspiration, or that the practice of faith with all its demands of the lived life carried them along the way.

The abbot then is a man concerned to encourage his disciples to grow into their unique fullness as creatures of God and since no two are alike his daily nourishing, sustaining, correcting will be different in each case. In saying that he should ‘love as he sees best for each individual’ (6.14) the Rule coins a happy phrase. This is the good shepherd who knows his sheep and who adapts his loving care to the needs of each. St Benedict makes frequent use of the vocabulary of love, and it comes across nowhere more strongly than in the great image of the abbot as a good shepherd, the good shepherd of St John’s gospel who cares for his sheep.

Caring is a word in such constant use – community care, a child in care – that it has become difficult to get back to its full meaning. It is a word much used in the second chapter in describing the role of the abbot, and it occurs elsewhere when the Rule discusses the abbot’s care for the monk in trouble (27, 28). The image of the good shepherd brings this out, for it is the mark of the hireling to care nothing for the sheep while the good shepherd in contrast knows his own and his own know him, that reciprocal personal knowledge without which any complete caring is impossible. Caring involves healing, and the work of the abbot is also that of the physician, the skilful doctor. For St Benedict is setting up a caring community and when in his great chapter at the end, chapter 72, he concludes by laying down the supreme principle that what actually counts is love, he is giving a blueprint for any caring community. He knows that it is hard work, and that the brothers will have to labour hard at it. Nothing could be less vague or romantic than his treatment throughout the Rule of the way in which real love is to be fostered between members of the community, and that great panegyric at the end must not be taken out of the context of all the other places in which he talks about love in its most practical terms (as for example in the case of hospitality). The abbot, who is the exemplar of the qualities that all the brothers should have, must in the first place actually be good and loving rather than being able to talk about it, and he must show equal love to all. Only against this secure background of love can healing begin to take place, that life-long process which everyone needs. The abbot must know both how to heal his own wounds and those of others (46.6). In the first place he has to be skilled at diagnosing individual ills, so that he does not take the easy short cut of handing out the same cure to each. Instead the Rule is insistent that someone needs kindness, someone else needs severity, and while one will respond to reproof another will respond to persuasion.

It is never easy to live with other people; it is much simpler to be a saint alone. In a community, or a family, or a parish, or a group of friends, it is inevitable that we are going to be hurt time and again by others, sometimes so deeply that the pain retains its power for years afterwards. We wound each other so easily and so quickly. The Rule knows that these small cuts and bruises, these knocks and blows, the strange and hurtful things that we do to one another, can, if they are left untended, soon develop into running sores. That is why St Benedict orders the Lord’s Prayer to be said twice a day so that ‘forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us’ will be a constant reminder of the vital necessity of practising forgiveness. To go round like Cain with hate of our brother leads to disaster. So the heart of community is forgiveness. We can only be healed through forgiveness, and we can only gain freedom through it. ‘Forgiveness is the greatest factor of growth for any human being.’ But it is demanding; it is an exercise which asks of us honesty and love. It brings us face to face with our pain, it forces us to confront it and deal with it, and St Benedict would add, the sooner the better, since unless they are cauterized wounds grow and fester. It is only too easy to keep up an internal conversation by which I chew over that hurting remark, or that undeserved happening, or I refuse to forget some slight, or I go on saying ‘It isn’t fair’ over and over again to myself. Then what began as quite a small grudge or resentment has been nursed into a brooding cloud that smothers all my inner landscape, or has become a cancer eating up more and more of my inner self. St Benedict is absolutely adamant about this. He describes it as murmuring or grumbling in the heart, and he is quite clear that it must be rooted out before it starts to do terrible damage. ‘First and foremost, there must be no word or sign of the evil of grumbling, no manifestation of it for any reason at all’ (34.6). For he knows that it is destructive of peace of mind, both for the individual and the community. Peace is an overriding objective of Benedictine life, and pax has become a Benedictine watchword. ‘Let peace be your request and aim’ (Prol. 17); ‘seek peace and pursue it.’ Lack of interior peace threatens the whole fabric of the community and that is why St Benedict starts here, where that lack of peace begins, inside ourselves, with this murmuring which fragments and destroys us. When there is so much concern today with the peace of the world, when peace movements multiply and peace groups proliferate, and the discussion of peace-making becomes more and more urgent and insistent, St Benedict brings us back to this very simple and basic root: peace must start within myself. How can I hope to contribute to the peace of the world when I cannot resolve my own inner conflicts? When I am torn apart by my own internal stress? St Benedict is saying once again that I must take responsibility for myself, and that if I hope to achieve great things in the cause of peace I must start with peace at home, within myself. The chain of violence must end in me; this is the start of peace and where world peace must begin.

When things go wrong in the community and there is failure of one sort or another then this same readiness to take responsibility must not be evaded. After failure comes confession and then finally forgiveness. St Benedict chooses to illustrate this with the most practical of all occasions, damage in the storeroom. ‘If someone commits a fault in the kitchen, in the storeroom, in serving, in the bakery, in the garden, in any craft or anywhere else – either by breaking or losing something or in any other way in any other place, he must at once come before the abbot and the community and of his own accord admit his fault and make satisfaction’ (46.1–4). In other words, he is insisting on owning up at once. What a childish phrase! And yet it means recognizing the real importance of taking responsibility for one’s actions, being ready to say we are sorry, being w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Author biography

- Title page

- Dedication page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Forewords

- Preface to the New Edition

- Explanation

- I St Benedict

- II The Invitation

- III Listening

- IV Stability

- V Change

- VI Balance

- VII Material Things

- VIII People

- IX Authority

- X Praying

- Notes on Further Reading