- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

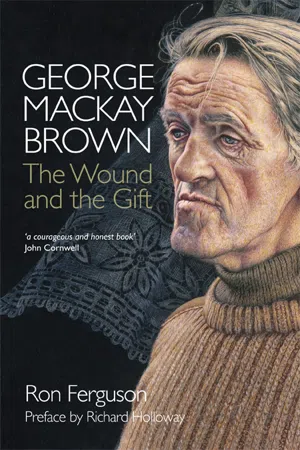

George Mackay Brown is one of the 20th century's finest writers. This biography sweeps us along on an enriching literary and spiritual journey..Draws on unpublished letters, conversations with the enigmatic Bard's friends and well-known writers. Shortlisted for the Saltire Award Best Research Book of the Year.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access George MacKay Brown by Ron Ferguson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Sweet

Georgie Broon

Wearing pyjamas and dressing gown, Georgie Broon – as he is known in Stromness – lies on top of his bed, looking at the ceiling, wondering what will become of him.

He is a serious man. Before his life changed for the worse, his adolescent self used to mooch around the tombstones of Warbeth cemetery on the edge of Stromness, reading the inscriptions. He wishes he were free to do that now.

Warbeth is one of his favourite haunts. Down near the sea, with its clashing tides and the cliffs of Hoy as dramatic backdrop, it has an elemental feel. He runs yet again in his mind the tape loop of his now-dead father saying to him: ‘There are more folk lying dead in this kirkyard than there are living nowadays in the whole of Orkney’.

He pictures his father. He misses him.

In his reverie, the image of one particular tombstone that has held his imagination in thrall since he frst stumbled upon it comes again unbidden. It is the memorial of a girl, Ellen Dunne, who died in 1858 at the age of 17. He can see the words, which both draw him and appal him, on the ceiling. He knows them off by heart. He vocalises them silently.

Stop for a moment, youthful passer-by,

On this memento cast a serious eye.

Though now the rose of health may fush your cheek,

And youthful vigour, health and strength bespeak,

Yet think how soon, like me, you may become,

In youth’s fair prime, the tenant of the tomb.

At a time when other young men were playing football or seeking to persuade comely Orcadian lassies that they might be more comfortable with their clothes off, George had been worrying about human transience and death. He would write a beautiful poem, ‘Kirkyard’, on this subject:

A silent conquering army,

The island dead,

Column on column, each with a stone banner

Raised over his head.

A green wave full of fish

Drifted far

In wavering westering ebb-drawn shoals beyond

Sinker or star.

A labyrinth of celled

And waxen pain.

Yet I come to the honeycomb often, to sip the finished

Fragrance of men.

Now he is in a sanatorium in Kirkwall, for the second time, suffering from tuberculosis. His exquisitely painful reverie is interrupted by a familiar, irritating sound: the other patient in this small ward has switched on his radio. George can hardly bear it. He sighs. He wants silence.

He also wants to hit this man. Why can people not tolerate quietness? Why do they have to fill up every bloody minute with loud noise? He must speak to the superintendent to complain.

Some of the patients get on his nerves. not long ago, a young man had put snow down his back. George had punched him with a ferocity that surprised both the other man and himself.

His violent thoughts trouble him. They seem to come out of nowhere.

He picks up a book, and tries to read, but he cannot concentrate. Mercifully, his room-mate switches the radio off and goes out for a walk. He is hardly out of the door when George rolls off his bed, lifts the offending radio and beats it violently against the wall.

Tuberculosis had first been diagnosed in 1941, when George Brown presented himself at Kirkwall’s hospital for a medical examination after receiving his call-up papers for military service. The army doctor sent him straight to Eastbank Sanatorium.

There had been hints and shadows. As well as being uncomfortably close to the lit-up sights and sounds of random death – flying shrapnel at a hamlet near Stromness had caused the first civilian death of the Second World War – George had also inhabited a personal war zone. In the aftermath of a debilitating bout of measles, his battle was fought in chest and heart and mind. The weakness in his lungs had been compounded by his cigarette-smoking. He often found himself gasping for breath.

Now, lying on his bed, George had time to reflect on his life so far.

The youngest of five surviving children, he was born on 17 October 1921 in Stromness, with the sea lapping against a pier outside the door of the family house. The town, with its twisting, narrow main street and its tiered closes – made even more romantic by names like Khyber Pass and Franklin Place – grew up, as the writer known as George Mackay Brown was to say, ‘like a salt-sea ballad in stone’.

Stromness’s prosperity had grown during the expansion of trade in the eighteenth century. The town’s rise to prominence as the principal recruiting ground for the Hudson’s Bay Company in Canada in the nineteenth century increased its importance. The residents of Stromness had become used to the sight of visiting mariners and – during the First World War – soldiers in uniform making their noisy and unsteady way through the town. By the 1920s, however, Stromness was less prosperous and certainly less boisterous, especially after all its thirty-eight taverns were closed by a public vote. Describing the Stromness of his birth as ‘old and gray and full of sleep’, George would later observe: ‘It was a very depressed local community that I was born into’.

Young Georgie grew up in a world of stories. He heard tales about the notorious Stromness-born pirate John Gow, and about the doings of Orcadian midshipman George Stewart, who sailed on the Bounty and joined the mutineers. He also learned about the adventures of John Rae, who was blacklisted by the London naval establishment when he came back from Canada with strange stories about the fate of the expedition to find the northwest Passage, led by Sir John Franklin. Well-founded reports by the highly regarded Orcadian explorer, suggesting that the starving Franklin crew had engaged in cannibalism, caused outrage in London. Lady Franklin and novelist Charles Dickens made sure that Rae would receive none of the awards that his pioneering work merited.

Tales about press-gangs, shipwreck and smuggling were part of a communal folklore which was a wonderful resource for a would-be poet and novelist.

As a boy, Georgie had what he remembered as a secure childhood in Stromness. As a child between the ages of fve and eight, he would say, Stromness seemed to be like Bethlehem, where a child might not be surprised to meet angels, shepherds or kings on a winter night. He would later mythologise Stromness, using its norse name of Hamnavoe – ‘haven inside the bay’ – to situate it as a fabulous place in a fabled time.

Contemporaries said that he had inherited the sweetness of his naturally cheerful Gaelic-speaking mother, Mhairi Sheena Mackay. Brought up in the strict Calvinist ethos of the Free Presbyterian Church, Mary Jane – as she was known in Stromness – had moved to Orkney from Strathy in Sutherland at the age of 16 to take up work in the Stromness Hotel.

George was a confident and aggressive footballer; but there were shadows over his childhood. At the age of four or five, he woke up one night and discovered that his mother wasn’t there. He later described his fear: Probably she was out visiting a neighbour, or at a concert or kirk soiree. I was overwhelmed by a feeling of desolation and bereavement: she was gone, she would never never come back again … I made the night hideous with my keening. On another occasion, he was sitting on the doorstep at home when a tinker woman came to the door selling pens and haberdashery. He fainted. For years thereafter, he had nightmares about being abducted by tinkers.

Another vivid memory was of the crew of an Aberdeen trawler staggering drunk in the street. The image of those out-of-control strangers on a quiet street filled young George with dread. One new Year’s Day, he saw two local fishermen making their way unsteadily and rowdily along the street. He knew them both as peaceable men, and the sight of them behaving in this troubling way sent him hurrying home, white in the face.

When he was 14 years old, he was more seriously destabilised. His depressive uncle, Jimmy Brown, who believed there were fairies in his garden and who often reported seeing apparitions of ships’ masts leaving Stromness, went missing; a few days later, his body was fished out of Stromness harbour.

George’s imagination was haunted by Jimmy Brown. While there was a sweetness and shy charm about the boy, it was accompanied by fearfulness and by a taste of grey depression in the mouth.

School was not a happy place for him. He described Stromness Academy as an immense, forbidding building, more like a prison. There was no room, he said, for delight or wonderment – even in the teaching of English. The boy who would become one of the finest poets and prose stylists of his generation hated the instruction in grammar. Even late in life, he maintained that he could not parse a sentence.

He remembered writing his first poem, at the age of about 10, on a scrap of paper. It was in praise of Stromness; his parents were very pleased. Sombre and morbid poems came in a spate during an adolescence which, he said, was full of shame and fears and miseries. One symptom was that whenever my mother left the house to go shopping, I was convinced every time that she would never come home again. I would shadow her along the street, and dodged into doorways if she chanced to look back. I can’t remember how long this state of affairs went on, but it’s certain that a part of my mind was unhinged.

His anxieties were not helped by the bout with measles, which affected both hearing and sight, at the age of 15.

To learn more, I drove out to Quoyloo in rural Orkney to talk to Morag MacInnes, Orcadian poet and writer of short stories, whose father was George’s best friend at school. Ian MacInnes, who would grow up to be a gifted artist – and a passionate atheist and socialist – would play a continuously significant part in George Mackay Brown’s journey.

‘When George got ill, it happened fairly quickly that he couldn’t kick a ball any more,’ Morag told me. ‘When he discovered that he did like literature, gates and doors opened for him, but it was a very solitary pursuit. My dad didn’t discover literature, and George wasn’t particularly close to anybody else in the class. There wasn’t anybody else who was finding the beauty of Keats and Shelley and Wordsworth the way George was. Increasingly, as he got depressed, he had that whole adolescent thing where he had a terrible distaste for physical contact, and he was ashamed of his sexuality – whereas by that stage my dad was having innocent tumbles in the heather, and the other boys were too. From about the age of 15, George was really untouchable and untouched.’

George’s fragile state worsened on the morning of 11 July 1940, when he was awakened by a sound he had never heard before. His brother, Hughie, was weeping downstairs. The police had called on Hughie at his place of work and told him that his father had died suddenly of a heart attack earlier that morning.

John Brown, who was 64 years old, had retired from his job as a postman in 1936, crippled with arthritis. He had managed to find work as a ‘hut-tender’ on the island of Hoy. His cheerful demeanour masked a depressive tendency. Young George had been much troubled by hearing his father pace backwards and forwards in his room – ‘the man inside was a stranger to me’ – speaking to himself about his troubles. After his retirement as a postman, when he had no pension and felt himself to be a burden on his family, he had largely lost his desire to live. ‘My next suit will be a wooden one,’ he had said when he bought a new outfit. now he lay in his coffin in the little bedroom downstairs, ‘more remote than a star’. George Mackay Brown would later write: ‘Touch the forehead,’ said someone. There was a belief that you must touch a dead brow, otherwise pictures of the person would linger and disturb you in some way or other. I have never felt a coldness so intense as that touch. He had travelled such a far way from the wells and fires of the blood.

His father’s sympathy for people on the fringes of society – tinkers, tramps, fairground people, eccentrics – made a big impression on George, who would write: A quintessence of dust, he lies in a field above Hoy Sound among all the rich storied dust of Stromness. The postman had left the last door, he had quenched the fame in his lantern. The tailor had folded the finished coat and laid it aside. He was at rest with fishermen, farmers, merchants, sailors and their women-folk – many generations. I wish there was a Thomas Hardy in Orkney to report the conversations of those salt and loam tongues in the kirkyard, immortally.

Orkney’s own Thomas Hardy felt that his father had never been given his due. George would put that right in 1959 with the publication of his elegaic tribute to John Brown in his collection of poems, Loaves and Fishes. The poem, ‘Hamnavoe’, which George had started writing in 1947, celebr...

Table of contents

- George Mackay Brown

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- George Mackay Brown: Timeline

- Prologue

- CHAPTER 1 Sweet Georgie Broon

- CHAPTER 2 The View from the Magic Mountain

- CHAPTER 3 Scarecrow in the Community

- CHAPTER 4 Ministering Angels

- CHAPTER 5 'Men of Sorrows and Acquainted with Grieve’

- CHAPTER 6 The Odd Couple

- CHAPTER 7 A Knox-ruined Nation?

- CHAPTER 8 Home at Last

- CHAPTER 9 Poet of Silence

- CHAPTER 10 Tell Me the Old, Old Story

- CHAPTER 11 Making the Terrors Bearable

- CHAPTER 12 Orkney's Still Centre

- CHAPTER 13 Heidegger's Biro

- CHAPTER 14 Lost in the Barleycorn Labyrinth

- CHAPTER 15 The Trial of George Brown

- CHAPTER 16 Poetic Dwelling on the Earth as a Mortal

- CHAPTER 17 April is the Cruellest Month

- Epilogue

- Notes