eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Spirituality, Theology and Mental Health

Multidisciplinary Perspectives

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Spirituality, Theology and Mental Health provides reflections from leading international scholars and practitioners in theology, anthropology, philosophy and psychiatry as to the nature of spirituality and its relevance to constructions of mental disorder and mental healthcare.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Spirituality, Theology and Mental Health by Cook, Christopher Cook in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Psychology of Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Controversies on the Place of Spirituality and Religion in Psychiatric Practice

Summary

Recent controversies concerning the place of spirituality in psychiatry in the UK have reflected a variety of concerns among mental health professionals and service users. On the one hand, research and clinical interest in spirituality as a positive factor in mental healthcare has been on the ascendant. On the other hand, there have been concerns that the inclusion of spirituality within the practice of psychiatry crosses important professional boundaries. Boundaries are important for good professional practice, and three particular boundaries emerge in this debate as being of especial concern: the boundary of specialist expertise, the boundary between secular and religious spheres of interest, and the boundary between personal and professional values. Proper professional observance of these boundaries does not require that spirituality or religion be excluded from psychiatry (an impossible aim, in any case) but it does require that they be examined carefully and critically, both by individual clinicians in the course of their practice and by the professional community in the course of ethical, academic and clinical debate.

Spirituality and religion have attracted increasing interest in the field of mental healthcare in recent years, among academics, clinicians and service users. Research evidence suggests that better attention to spirituality might improve treatment outcomes, and service users have expressed a desire that spirituality and religion should be addressed during the course of treatment. However, there has been significant professional and academic debate as to the merits and dangers of this trend. This chapter will consider the nature of spirituality, the increasing interest given to it in academic and professional debate and the nature of the controversies that have arisen. In particular, attention will be given to examining the nature of the professional boundaries that have been identified as a concern where spirituality and religion are to be addressed in clinical practice and their proper management.

The nature of spirituality

Spirituality is not easily defined and represents a disputed concept about which there has been much debate (Cook 2004; Sims and Cook 2009). Some would argue that it is distinct from religion and others that it amounts to much the same kind of thing. But, religion is also not easily defined, and the oft promoted view that spirituality is individual, subjective and experiential, as contrasted to the institutional, traditional and doctrinal nature of religion, does justice neither to the social and traditional aspects of spirituality nor to the individual experience of religion. For many, spirituality and religion are about meaning and purpose in life, but it is doubtless the case that meaning and purpose are often found by others without spirituality or religion ever being mentioned. Similarly, even though many people understand spirituality in terms of relationships (for example with self, others and a higher power or wider order), it is difficult to define those relational aspects of spirituality that cannot otherwise be framed in purely psychological terms, unless perhaps they are concerned with transcendence (and even here, psychological accounts abound).

Despite these observations, spirituality is preserved here as a term that is seen to be useful, partly because it is so widely used (and hardly likely to be abandoned in the foreseeable future) but also because it is thought to retain some validity. Further, it is useful to have a term that can be employed to refer to a universal aspect of human well-being (even if it is not universally accepted), without introducing the specificity and particularity that religion usually implies.

Spirituality and mental health

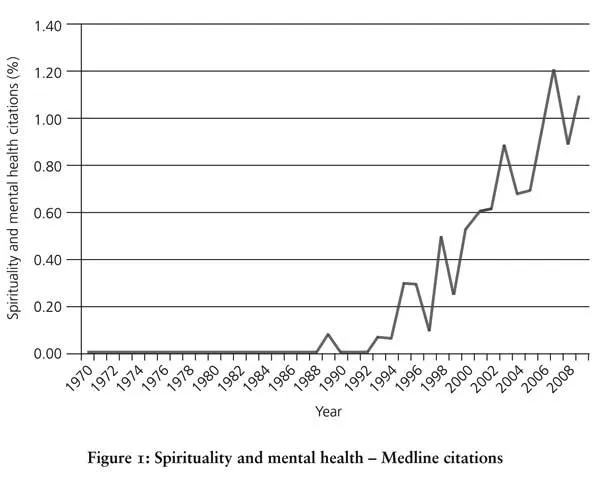

A search of Medline citations reveals that increasing numbers of papers on spirituality have been published in the healthcare literature since the early 1980s (Cook 2004). The proportion of papers on spirituality and mental health has similarly been rising year on year, and this increase does not simply reflect the increasing numbers of papers published year on year but actually represents a growing proportion of papers in the database (see Figure 1).

When the first edition of the widely cited and influential Handbook of Religion and Health was published in 2001 (Koenig, McCullough et al. 2001), it reported that almost 80 per cent of 100 studies on religion and measures of well-being such as happiness, life satisfaction and morale found a positive correlation. Religious involvement was found to be associated with (among other things) low hostility, higher levels of hope, optimism and self-esteem, less delinquency among young people and greater social support and marital stability.

The Handbook reviews of research on specific psychiatric disorders generally demonstrated positive effects of religiosity. For depression, for example, it was concluded that religious affiliation and social involvement (where associated with intrinsic religiosity) were generally associated with less depression, that religious people recover more quickly and that religious involvement helps people to cope with stress. Of 68 studies, 84 per cent showed an inverse relationship between religious involvement and suicide. Intrinsic religiosity was, on the whole, found to buffer against anxiety. Nearly 100 studies were found to support a deterrent effect of religion against substance misuse. While religion was not thought to influence the occurrence of the psychoses, it was thought to provide an important coping resource to people suffering from such conditions. In general, however, it was also acknowledged that the methodology of many studies left much to be desired, and particularly that more longitudinal studies were needed.

When the second edition of the Handbook was published, just over ten years later (Koenig, King et al. 2012), the conclusions of the first edition generally seemed to be reaffirmed and supported by more recent research. Thus, for example, 78 per cent of 224 studies on well-being undertaken since the year 2000 found positive associations with greater religiousness. But as in the first edition, not all findings were positive. For example, out of a total of 443 quantitative studies on depression included in the first and second editions, 61 per cent found that greater religious/spiritual involvement was associated with less depression or faster recovery, but 22 per cent found no association and 6 per cent found an association with greater depression. Furthermore, some of the studies finding no association or finding an association with greater depression were rated as being of good quality methodology. The authors note a variety of possible reasons for this. For example, in contrast to the United States, in less religious but affluent countries it is suggested that people suffering from depression might turn to religion as a coping mechanism and thus that an apparent association between religion and depression might emerge.

The rising numbers of published research papers internationally and the associated scientific debate have been paralleled by an increasing level of public and professional debate. Much of this has taken place in the United States, but the debate in the United Kingdom will be taken here as an example of the way that spirituality has become a topic of increasing interest in the field of mental health. In particular, interest in this topic within the Royal College of Psychiatrists is taken as an example and indicator of professional and academic interest generally, but it is of note that during the same period the debate has also reflected the interests of service users, policy makers and other professional groups (Mental Health Foundation 1997; Mental Health Foundation 2002; Mental Health Foundation 2007). Indeed, service user concerns and policy initiatives are almost certainly among the key factors that have fuelled interest and driven change in services (Eagger, Richmond et al. 2009).

In 1991, HRH The Prince of Wales, addressing the Royal College of Psychiatrists as its patron, drew attention to the spiritual task that is at the heart of mental healthcare:

We are not just machines, whatever modern science may claim is the case on the evidence of what is purely visible and tangible in this world. Mental and physical health also have a spiritual base. Caring for people who are ill, restoring them to health when that is possible, and comforting them always, even when it is not, are spiritual tasks. (HRH The Prince of Wales 1991)

In 1993, successive presidents of the Royal College of Psychiatrists addressed the subject of spiritual care in their lectures at College meetings. Professor Andrew Sims, in his valedictory lecture, warned members that they ignore the topic at their patients’ peril:

For too long psychiatry has avoided the spiritual realm, perhaps out of ignorance, for fear of trampling on patients’ sensibilities. This is understandable, but psychiatrists have neglected it at their patients’ peril. We need to evaluate the religious and spiritual experience of our patients in aetiology, diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. (Sims 1994)

Reflecting on why psychiatrists neglect the spiritual, he suggested that there might be several reasons:

(a) It is considered unimportant.

(b) It is considered important but irrelevant to psychiatry – like assuming the hospital has a safe water supply.

(c) We feel we know too little about it ourselves to comment, or even to ask questions.

(d) The very terminology is confusing and hence embarrassing; it is not respectable.

(e) There may also be an element of denial in which it is easier to ignore this area than explore it as it is too personally challenging. (Sims 1994)

Professor John Cox, as the incoming president in the same year, emphasized the importance of religious perspectives as an aspect of culturally aware psychiatry in a plural society:

[I]f mental health services in a multi-cultural society are to become more responsive to ‘user’ needs then eliciting the ‘religious history’ with any linked spiritual meanings should be a routine component of a psychiatric assessment, and of preparing a more culturally sensitive ‘care plan’. (Cox 1994)

In 1997, the Archbishop of Canterbury was invited to address an annual meeting of the College (Carey 1997). In the course of asking how the barriers between religion and psychiatry might be transcended, he noted the common inheritance that they share. Both recognize health as something ‘beyond the physical’. Both value faith, hope and love (although psychiatry might not so often use this language). Because they share so much and yet retain their own distinctiveness, he argued that religion and psychiatry actually need each other. On the one hand, religion needs the psychological and professional insights of psychiatry. On the other hand, psychiatry needs to understand the experiences associated with the religious quest, at least if its practitioners are to find any empathy with the many users of mental health services who are themselves associated with or engaged in this quest. Moreover, the Archbishop asserted, society needs religion and psychiatry to work together for the good of people who suffer from mental disorders if it is to respond effectively to the needs of people with mental disorders in primary care and in local communities.

In 1999, a Special Interest Group for Spirituality and Psychiatry (SPSIG) was formed within the College, under the founding chairmanship of Dr Andrew Powell, with a view to promoting professional debate on spirituality and psychiatry (Shooter 1999; Powell and Cook 2006; Powell 2009). Among other things, the group was established as a forum within which to discuss:

- ‘the significance of the major religions which influence the values and beliefs of the society in which we live, also taking into account the spiritual aspirations of individuals who do not identify with any one particular faith and those who hold that spirituality is independent of religion’;

- ‘specific experiences invested with spiritual meaning, including the meaning of birth, death and near-death, mystical and trance states to distinguish between transformative and pathological states of mind’;

- ‘protective factors which sustain individuals in crisis and otherwise contribute to mental health’. (Shooter 1999)

At the time of writing, the membership of the SPSIG stands at nearly three thousand.

Within a decade, the topic of spirituality had thus moved from something rarely or never mentioned within public and professional discourse at College meetings to being a topic that attracted sufficient interest to warrant the forming of a new Special Interest Group. In 2009, just a decade after this, a book conceived and written largely by members of the SPSIG and published by Royal College of Psychiatrists Press outlined the current state of the field of spirituality and psychiatry in clinical practice (Cook, Powell et al. 2009). Two years later, the College adopted as policy a position statement making recommendations for psychiatrists concerning spirituality and religion (Cook 2011), a statement that had also been drafted and proposed by the SPSIG.

The contemporary debate

The contemporary debate about spirituality and mental health arises in the context of a much longer history of tension between religion and psychiatry. From the very birth of psychiatry there seems to have been a desire to establish a distance from religion, perhaps as a part of the need to affirm scientific credentials for this new medical speciality (Koenig, King et al. 2012, pp. 30–1). This distance became coupled with more active antagonism on the basis of various allegations that religion is associated with emotional immaturity, guilt, neurosis or even major mental illness (Neeleman and Persaud 1995). However, the relationship has...

Table of contents

- Copyright information

- Contents

- Author Affiliations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Controversies on the Place of Spirituality and Religion in Psychiatric Practice

- 2. ‘I’m spiritual but not religious’

- 3. What is Spiritual Care?

- 4. Augustine’s Concept of Evil and Its Practical Relevance for Psychotherapy

- 5. Exorcism

- 6. The Human Being and Demonic Invasion

- 7. Religion and Mental Health

- 8. Transcendence, Immanence and Mental Health

- 9. Thriving through Myth

- 10. Spirituality, Self-Discovery and Moral Change

- 11. ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’

- Conclusions and Reflections