eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Postcolonializing God

New Perspectives on Pastoral and Practical Theology

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Postcolonializing God examines how African Christianity can be truly a postcolonial reality and explores how people who were colonial subjects may practice a spirituality that bears the hallmarks of their authentic cultural heritage, even if that makes them distinctly different from Christians from the colonizing nations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Postcolonializing God by Emmanuel Y. Lartey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 God Postcolonializes

And what is Christianity but a great hybrid, comprised at the urban crossroads of the Roman Empire? It exploded into mission on Pentecost: A vision of a multilingual understanding dancing in dissident flames upon the heads of its first community.1

A postcolonial reading of the ‘Tower of Babel’ story

The aetiological story recorded in Genesis 11.1–9 seeks to offer a narrative explanation of the diversity, especially in languages, observable in the world. The story is of a migratory people united in language travelling from the east and settling – doubtlessly for a period until the resources for sustenance ran out – in a fertile plain. These migratory people appear to have found a place where they might settle for a significant duration of time. Alongside their desire to ‘settle’ (v. 4c ‘lest we be dispersed over the face of the whole earth’) is also a wish to be remembered and honoured by their descendants (v. 4b ‘let us make a name – shem – for ourselves’). For this reason they may be described as ‘Shemites’, a people seeking to make a name for themselves. ‘Colonialism’, declares Brazilian-born US theologian Vítor Westhelle, ‘operates by interest (i.e. financial gain) but is motivated by desire to make a name for oneself’.2 Their chosen means of achieving these goals was to ‘build a city and a tower’ (v. 4a). Their settling in one place bespeaks their desire to uphold a unity of place. So as to ensure that they are not scattered they appeal to the security of being in one place. They embark on a project to make themselves great, be remembered as a powerful people, remain securely in one place and be a united people. Now, none of these desires can be construed as being ignoble in itself. Troublesome, exacting and rather a humbug (‘hubris’) perhaps, but by no means dishonourable or destructive. These ‘Shemites’ (name seekers), then, are seeking security of place, greatness of name and the power of oneness, without reference to or relationship with the God of All Creation, whose wishes and purposes in creation they appear to have lost sight of.

The narrative continues by asserting that YHWH comes down to visit and take a look at what they had built, perhaps, as the story implies, disturbed by the tower which had its top ‘in the heavens’ (v. 4a) suggesting an intrusion into the heavenly realm. YHWH’s curiosity has been ignited by that which the ‘children of man’ (v. 5) had built. The divine response is both enigmatic and purposeful. It is premised on the unity of the people and especially their one language. This kind of unity and oneness of language has given them the means to intrude upon the divine realm. The Shemites are seeking for themselves that which transcends the bounds of their humanity in relationship to God, while also flying in the face of the divine will and desire for all humanity. Here, on a postcolonial reading of this story, it is my view that what the Creator recognizes in the resolve of the Shemites is a departure from the diversity of creation. The oneness of language and culture had produced a hegemonic, power-hoarding, name-seeking group of humans whose intention to dominate would be unchallenged (v. 6). Their desire to control, dominate and conquer all, even the heavenly realm, would be unstoppable. The divine purpose implicit in the diversity of all creation, that there would be ‘checks and balances’, many different voices to listen to, and a range of possible cultures to embrace, had been endangered. The variety that was intended to be the characteristic of humanity was at risk. Instead of ‘filling the whole earth’ (Gen. 1.28), the express desire and purpose of the Creator repeated to Noah and his family after the Flood (Gen. 9.1), these people wanted to settle and not be dispersed throughout the earth. This group of humans desired total control, hegemony, prime place currently and for posterity. They would debase and obliterate any differences among them – in point of fact they would not allow or recognize any differences. They had one language. They would insist on their way alone as being the way for all to follow. This is the essence of colonization. The language, customs and ways of life of one group are imposed on all. Everyone who comes under the influence of the colonizer must succumb to the colonizer’s way or else be crushed. Everyone must ‘speak the same language’ – a supremely monoculturalist insistence – or be brought into line, forcibly if necessary, eliminated, expelled or else considered uncultured, uncouth, deviant even deranged. God, the Creator of diversity, cannot abide such hegemonic control. God ‘confuses (babel) their language’ (v. 7). Now each must have their own voice. Each must speak for themselves. The many voices of creation would sound again. God also disperses them over all the earth. God pluralizes their discourse, their culture and their manner of life. The diversity of creation is re-affirmed. The ‘filling of the whole earth’ is promoted. This action of God has been interpreted by many commentators as ‘punishment’. It need not be punitive. Moreover, it need not be seen as the action of a fearful, insecure deity. Instead I see this divine action as a re-affirmation of the purpose of creation, a revalorizing of the diversity built into the very sinews of creation.

In postcolonial terms, at least three lessons can be derived from this narrative. First, that the existing diversity of human languages and cultures is the result of divine redemptive action. God acts to ensure that there is diversity in humanity’s culture. Second, that diversity is preferred by God to hegemony. Unity or uniformity directed towards the hubris of intrusive power and self- (or people-) aggrandizing control contradicts the Creator’s will and purpose in humanity. Stated simply – God prefers diversity. Third, that God acts within the global community to affirm human diversity. God is not inactive in the face of hegemonic control by any human community. God acts to dispel and diffuse hegemony. God not only decolonizes (scatters the people) but also postcolonizes (confuses the language) of human community. It is as such perhaps in the confusing (babel) of the language of the people that we see most clearly the postcolonializing intent of God. Language, one of the most salient characteristics of culture and politics, is what is diversified, symbolic of God’s counter-hegemonic and pluralizing activity.

Jesus and people of other faiths: Practical theology and religious pluralism in the Gospels

One intriguing aspect of the life of Jesus portrayed for us in the Gospels has to do with his encounters with people of different faiths. On several occasions, and we shall consider only four here, Jesus either meets with a person of a faith other than his own Jewish tradition or else he makes reference to people of other faiths in stories and parables he tells to illustrate his teaching.

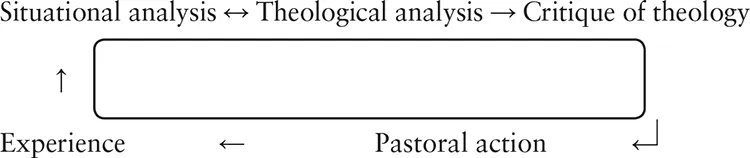

I am approaching these testimonies of Jesus’ encounters with people of differing faiths as a practical theologian and so do so with the methodologies most favoured by practical theologians. Practical theologians typically recognize that the starting point of their practice as well as their academic work lies in the exigencies of people’s experiences of life – especially life’s pains, sorrows, losses, traumas and disasters. Pastoral theologians in particular seem to deal mostly with experiences of pain and loss. Occasionally the joys as well, but by and large pastoral theologians come into the picture most critically when and where there is or has been some suffering, loss or tragedy. The experience, the case study, the self report, the client’s narrative – these are the points of entry for most pastoral care (and counselling) as well as pastoral theological work. My pastoral theological work tends to flow in a pastoral cycle that I have described in the following way.3

Although any of the nodal points in this diagram could notionally be the starting point, more often than not the experiential tends to be the point of entry into the pastoral cycle. I am always at pains to point out that regardless of the starting point it is imperative, if a truly pastoral engagement is desired, that all the phases (or stations) in the cycle be ‘performed’ or gone through. As I have pondered the issue of religious pluralism, an increasingly observable feature of our postcolonial global scene, I have found it useful to start with a theological mediation, specifically an exploration of the Gospels, Christian scriptural references that report directly on the practice, experience and life style of Jesus of Nazareth. For Christians these texts are foundational for their life, faith and practice. It is illuminating therefore to ask, ‘What was Jesus’ attitude to persons of other religious faiths? How do the Gospels portray Jesus in the practice of engaging people of faiths other than his own?’ For many Christians this is a question they warm to. It finds resonance with their theological orientation to life. I find however that they have hardly ever been asked or else asked themselves these particular questions in relation to the following Gospel texts, and they are often at a loss as to how to begin to address them.

Let us look at four New Testament pericopes that introduce Jesus’ interactions with or reference to persons of different religious and ethnic origins, namely: the Roman centurion (Matt. 8.5–13; Luke 7.1–10); the Canaanite (Syro-Phoenician) woman (Matt. 15.21–8; Mark 7.24–30); the Samaritan leper (Luke 17.11–19) and Jesus’ parable of the ‘Good’ Samaritan (Luke 10.30–7). The point of referring to these Gospel stories is that in each of them Jesus encounters or engages someone of a different religious tradition than his own.

The greatest faith in Israel: A Roman centurion (Matt. 8.5–13)

It is very likely that the Roman centurion encountered in this story adhered to a form of the Roman religion practised at the time. Roman religion in the time of Jesus was conceived of and practised as a contractual relationship between humans and the forces believed to control people’s existence and well-being. Roman religion was a mixture of rituals, taboos, traditions and observances gathered over the years from a number of different sources. The result of such religious attitudes was two particular forms of practice. One, a state cult which had influence on political and military events, and the other a private/domestic practice in which the head of the family oversaw rituals and prayers in a manner analogous to the way representatives of the people performed public ceremonials. A pontifex maximus headed up Roman state religion with a pontifical college made up of the rex sacrorum (chief of rites and rituals), pontifices (priests), flamines (priests to individual gods) – with the flamen dialis (the priest of Jupiter) at the head, and the vestal virgins, who kept the flame of religion alive through their virginity and ongoing chastity.

Most of the Roman gods and goddesses were a blend of several religious influences. The Greek and the Roman pantheon looked very similar but for different names. Ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses were often also identified with them. Religious festivals were held throughout the year, the earliest forms being games. The commonest form of religious activity for the Romans required some kind of sacrifice, usually animal sacrifice. Worship of dead ancestors by families during the parentilia in the month of February was a deeply sacred occurrence. Since Roman religion was not founded on some core belief which ruled out other religions, foreign religions, e.g. the goddess Cybele (circa 204 bc) and the worship of the Egyptian gods Isis (Auset) and Osiris (Asar) (beginning of the first century bc), found it relatively easy to establish themselves in the imperial capital itself.

While the text does not specifically name the type of practice the Roman centurion was engaged in, in all likelihood he was a participant to some degree in the religion of his nation, culture and time period. In spite of the mélange that probably constituted his religious practice and its marked difference from the Jewish faith of Jesus, the Roman centurion is held up as an ideal exemplar of faith. Surprisingly, without urging him to repudiate his faith or convert to the faith Jesus proclaimed and lived, Jesus says: ‘Truly, I tell you, in no one in Israel have I found such faith’ (Matt. 8.10). This must have been a tantalizing statement to many. On a postcolonial reading, however, it suggests that Jesus was far more ready to recognize faithfulness wherever (and in whomever) he found it and to be less concerned about having everyone believe in the same way. The faith being commended was indeed faith in Jesus. However it was coming from a very different culture, nationality and religious heritage. It was from a foreigner, an uncircumcised, oppressive foreigner at that. Yet, Jesus finds n...

Table of contents

- Postcolonializing God

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 God Postcolonializes

- 2 Postcolonializing God in the USA

- 3 Postcolonializing Liturgical Practice: Rituals of Remembrance, Cleansing, Healing and Re-connection1

- 4 Transcending Colonial Religion: Brother Ishmael Tetteh and the Etherean Mission

- 5 Postcolonializing Pastoral Care

- 6 Postcolonializing God: A Theological Imperative

- Bibliography

- Index