eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

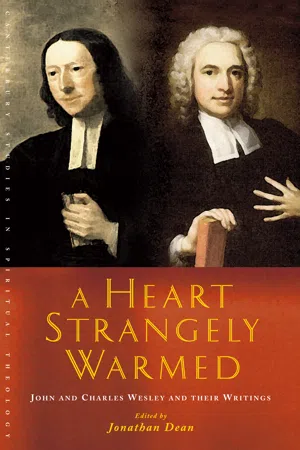

Canterbury Studies in Spiritual Theology

John and Charles Wesley and their Writings

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

John and Charles Wesley generated a heritage that reaches well beyond the worldwide Methodist movement which they founded. This collection of their essential writings shows how they harnessed resources from across the breadth of Anglicanism (and beyond) to forge a distinctive, dynamic and influential approach to religious experience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Canterbury Studies in Spiritual Theology by Jonathan Dean in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘A Disposition of the Heart’:

Finding Faith

Hark! the wastes have found a voice,

Lonely deserts now rejoice,

Gladsome hallelujahs sing,

All around with praises ring.

Lo! abundantly they bloom,

Lebanon is hither come,

Carmel’s stores the heavens dispense,

Sharon’s fertile excellence.

A Country Childhood

The foundations for John and Charles Wesley’s remarkable careers and of their distinctive practice of Christianity were laid in childhood in Epworth. Raised in this remote fenland environment and with a father busy about parish duties and encumbered by debt, the company of their siblings and the guidance of their mother were crucial. Susannah’s ordering of the Epworth Rectory, born out of the mixture of the necessities of their life and the deeply held Puritan inheritance of her own formation, was critical. We do not know much at first hand about their childhood, apart from some reminiscences from later life. At the time of his mother’s death in 1742, however, John did include in his journal reflections two letters from his mother: one to his father during one of Samuel’s absences from Epworth, and another to John himself, in response to a request for her method of child-rearing. Both offer a vivid portrait of the kind of life the Wesley children lived. Both equally give us a glimpse of how, for John especially, the child made the man, in self-reflection, rigorous religious practice and a keen sense of the need to be self-aware and accountable to God and others for one’s conduct and life.

To her son, Susanna outlined her parental regime thus:

24 July 1732

Dear Son,

According to your desire, I have collected the principal rules I observed in educating my family, which I now send you as they occurred to my mind, and you may (if you think they can be of use to any) dispose of them in what order you please.

The children were always put into a regular method of living, in such things as they were capable of, from their birth: as in dressing, undressing, changing their linen, etc. The first quarter commonly passes in sleep. After that, they were, if possible, laid into their cradles awake, and rocked to sleep; and so they were kept rocking, till it was time for them to awake. This was done to bring them to a regular course of sleeping, which at first was three hours in the morning, and three in the afternoon, afterward two hours, till they needed none at all.

When turned a year old, (and some before,) they were taught to fear the rod, and to cry softly,1 by which means they escaped abundance of correction they might otherwise have had, and that most odious noise of the crying of children was rarely heard in the house: but the family usually lived in as much quietness, as if there had not been a child among them.

As soon as they were grown pretty strong, they were confined to three meals a day. At dinner their little table and chairs were set by ours, where they could be overlooked, and they were suffered to eat and drink (small beer) as much as they would, but not to call for any thing. If they wanted aught, they used to whisper to the maid which attended them, who came and spake to me; and as soon as they could handle a knife and fork, they were set to our table. They were never suffered to choose their meat, but always made to eat such things as were provided for the family.

. . . The children of this family were taught, as soon as they could speak, the Lord’s Prayer, which they were made to say at rising and bed-time constantly; to which, as they grew bigger, were added a short prayer for their parents, and some collects, a short Catechism, and some portion of Scripture, as their memories could bear.

They were very early made to distinguish the Sabbath from other days, before they could well speak or go. They were as soon taught to be still at family prayers, and to ask a blessing immediately after, which they used to do by signs, before they could kneel or speak.

They were quickly made to understand, they might have nothing they cried for, and instructed to speak handsomely for what they wanted. They were not suffered to ask even the lowest servant for aught without saying, ‘Pray give me such a thing;’ and the servant was chid, if she ever let them omit that word. Taking God’s name in vain, cursing and swearing, profaneness, obscenity, rude, ill-bred names, were never heard among them. Nor were they ever permitted to call each other by their proper names, without the addition of Brother or Sister.

. . . When the house was rebuilt [after the fire of 1709], and the children all brought home, we entered upon a strict reform, and then was begun the custom of singing psalms at beginning and leaving school, morning and evening. Then also that of a general retirement at five o’clock was entered upon: when the oldest took the youngest that could speak, and the second the next, to whom they read the Psalms for the day, and a chapter in the New Testament, as, in the morning, they were directed to read the Psalms and a chapter in the Old, after which they went to their private prayers, before they got their breakfast, or came into the family. And, I thank God, the custom is still preserved among us.2

Perhaps even more revealingly, Susanna had written to her husband in 1712 describing both her management of the household and her growing role in the spiritual formation of the village in his absence, a role that clearly fitted her prodigious gifts but must have seemed improper in the culture of rural England at the time. Her arrangements immediately reveal much of the inspiration for the organization of the Methodists 30 years later.

. . . As I am a woman, so I am also mistress of a large family. And though the superior charge of the souls contained in it, lies upon you, yet, in your absence, I cannot but look upon every soul you leave under my care as a talent committed to me under a trust by the great Lord of all the families both of heaven and earth. And if I am unfaithful to him or you, in neglecting to improve these talents, how shall I answer unto him, when he shall command me to render an account of my stewardship?

As these, and other such like thoughts, made me at first take a more than ordinary care of the souls of my children and servants, so, knowing our religion requires a strict observation of the Lord’s day, and not thinking that we fully answered the end of the institution by going to church, unless we filled up the intermediate spaces of time by other acts of piety and devotion, I thought it my duty to spend some part of the day, in reading to and instructing my family. And such time I esteemed spent in a way more acceptable to God, than if I had retired to my own private devotions.

This was the beginning of my present practice. Other people’s coming and joining with us was merely accidental. Our lad told his parents: they first desired to be admitted, then others that heard of it, begged leave also. So our company increased to about thirty, and it seldom exceeded forty last winter.

But soon after you went to London last, I lit on the account of the Danish Missionaries. I was, I think, never more affected with any thing; I could not forbear spending good part of that evening in praising and adoring the divine goodness, for inspiring them with such ardent zeal for his glory. For several days I could think or speak of little else. At last it came into my mind: though I am not a man, nor a minister, yet if my heart were sincerely devoted to God, and I was inspired with a true zeal for his glory, I might do somewhat more than I do. I thought I might pray more for them, and might speak to those with whom I converse with more warmth of affection. I resolved to begin with my own children, in which I observe the following method: I take such a proportion of time as I can spare every night, to discourse with each child apart. On Monday, I talk with Molly; on Tuesday, with Hetty; Wednesday, with Nancy; Thursday, with Jacky; Friday, with Patty; Saturday, with Charles; and with Emily and Suky together on Sunday. With those few neighbours that then came to me, I discoursed more freely and affectionately. I chose the best and most awakening sermons we have. And I spent somewhat more time with them in such exercises, without being careful about the success of my undertaking. Since this, our company increased every night; for I dar...

Table of contents

- A Heart Strangely Warmed

- Contents

- ‘In All Things to Abound’: Editor’s Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 ‘A Disposition of the Heart’: Finding Faith

- 2 A Kingdom Set Ablaze: The Rise of Methodism

- 3 ‘Real’ Christianity and Wesleyan Theology

- 4 ‘Thou Universal Love’: The Wesleys and Predestination

- 5 ‘Changed from Glory into Glory’: Towards Perfection

- 6 ‘Names and Sects and Parties’: Opposition and Division

- 7 A ‘Catholic’ Spirit

- 8 ‘Wise and Faithful Stewards’: Justice, Economy and the Colonies

- 9 ‘My Remnant of Days’: Family, Friendship and Old Age

- Epilogue

- Suggested Further Reading