- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

A Faithful Presence

About this book

A Faithful Presence shows how churches work together and of the range of social action undertaken by churches locally and nationally – pastoral, advocacy, campaigning. It is designed to be of interest to clerical and lay audiences across denominations, including those who create, manage and implement social justice initiatives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Faithful Presence by Hilary Russell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Beginnings

[T]he Church represented an enduring, faithful presence … so that the flux and uncertainty all around could be more bravely confronted … In effect, the churches stood for an alternative way of life to that of the individualism and materialism which threatened our survival as a human society.

Don May and Margaret Simey 1989

What is the purpose of this short book? The impetus for it was to bring together and explore some of the themes underpinning the Together for the Common Good (T4CG) initiative. However, insofar as these reflect themes that have lingered with me over the past several decades, the book has a more personal flavour than originally intended. And because I have lived here for nearly all my adult life, the Liverpool context has very much informed my experience and thinking.

Scouse roots

Together for the Common Good began from the idea that there was still something to be learnt from the partnership of the church leaders here on Merseyside from the 1970s through to the 1990s, when the Roman Catholic Archbishop Derek Worlock, the Anglican Bishop of Liverpool David Sheppard and their Free Church colleagues, such as John Williamson, Keith Hobbs and Eric Allen and especially John Newton, worked so closely together.

Liverpool then was a very different place religiously, politically, socially and economically; and, as all cities are distinctive, it was different from other cities in England. Although sectarian tension between Protestants and Catholics was already on the wane, there were other social and economic pressures. Steep rates of poverty stemmed from, and were accompanied by, other problems. Unemployment was high. A lot of the housing in the city and surrounding areas was in poor condition. Population loss as the better qualified moved out in search of more promising opportunities meant growing disparity between income from rates and the city’s infrastructure costs. Although many members of the black community had roots in the city over several generations, they remained on the fringe of the social and economic mainstream. A succession of minority and coalition administrations over the 1970s and early 1980s meant a lack of strategic direction in the City Council. When the Militant Tendency came to power, the determined clash between local and central government further worsened the city’s reputation, deterred investors and distracted from properly serving the interests of residents and businesses. There were faults on both sides. On the one hand, the council exploited the city’s problems as part of a wider political agenda. On the other, the government’s punitive grant system made claims of unfair treatment persuasive and ‘even the Government’s own Audit Commission delivered a withering attack on the unpredictability and irrationality of the system which wholly reinforced Liverpool’s arguments’ (Parkinson 1985, p. 176).

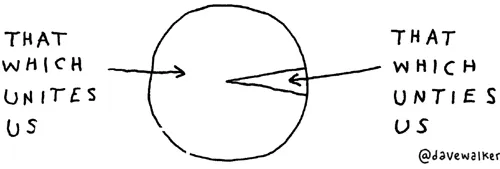

Liverpool at that time, therefore, desperately needed advocates and bridge builders, and it found them in these church leaders. They set aside what might have divided them in church terms to concentrate on what united them. Theirs was not a navel-gazing, inward-looking ecumenism focusing on the finer points of theological difference and negotiating institutional interest, rather it was an ecumenism of kingdom building. They wanted to bring practical improvements to people’s lives and to local neighbourhoods. And through their ‘better together’ ministry, they brought a gospel that really spoke to people, especially those who were disadvantaged and marginalized.

Reflection, conversation …

Reflection and action for change are complementary aspects of what T4CG is about. It is not just retrospective. It has become a growing movement of people and organizations interested in building commitment to the flourishing of all and exploring what this might mean and how it might be achieved in today’s social, economic and political circumstances. One focus is on engaging with people in a position to bring about change and who are open to collaborating with others to address social problems.

But it was also always intended that the initiative should result in different sorts of written materials and other tools for analysing the present-day context and exploring how different traditions of Christian thought can enlighten our search for social justice today. The website – www.togetherforthecommongood.com – lists resources and contains a range of opinion pieces and case studies.

An important book was published in 2015, Together for the Common Good: Towards a National Conversation, edited by Nicholas Sagovsky and Peter McGrail. Accompanied by a study guide, this assembles essays by academics, politicians and others contributing very varied perspectives on the common good, mainly from different Christian denominations and traditions but also including Jewish, Muslim and secular contributions and spanning different political perspectives. The word ‘conversation’ in the title is significant. Conversations took place among the contributors during the time they were writing, and the essays themselves are intended to prompt further conversations. The book’s timing was significant, coming as it did a few months before the General Election.

True godliness don’t turn men out of the world but enables them to live better in it and excites their endeavours to mend it. Christians should keep the helm and guide the vessel to its port; not meanly steal out at the stern of the world and leave those that are in it without a pilot to be driven by the fury of evil times upon the rock or sand of ruin.

William Penn 1682

Whether in the creation of manifestos or in the decisions of electors about how to cast their votes, elections always pose questions about reconciling self-interest and the common good. But in a time when politics often seem dominated by management-speak, the pertinence of reawakening debate on principles and values is not confined to the run-up to elections, rather it has to be part of a longer-term attempt to change the terms of the debate and move towards re-imagining politics.

… and action

The essays in Together for the Common Good represent attempts to interpret the world today from a UK standpoint. But the imperative behind the book is the need for action: action based on clear-eyed recognition of the reality facing us and wise judgement about a good way forward.

To say this is to say something about the quality of ‘conversation’ which must take place before there can be well-judged action which serves the common good. Conversation of this quality must be patient, attentive, well-informed and robust. It must be rooted in the needs and experience of local communities. It must be rooted in action and lead to action. Conversation of this quality is intended to change the world, in a transformative way to serve the common good. (Sagovsky and McGrail 2015, p. xviii)

Together for the Common Good primarily addresses the ‘common good’ part of T4CG. This present book focuses more upon the ‘together’ dimension, the relationships that can foster or inhibit joint working towards the common good. It draws in part on research that I led prior to and immediately following the T4CG conference in 2013, which included a large number of fieldwork interviews conducted by Gerwyn Jones of the European Institute for Urban Affairs, Liverpool John Moores University. This book has been informed by the research findings and includes quotes – with their permission – from some of the interviewees.

I take for granted that faith encompasses social action. It can take many forms: opening up the Church to the local community, taking part in neighbourhood projects, volunteering in a foodbank, spending time cleaning up the environment, sleeping out to raise funds for a homeless charity, or supporting social justice campaigns – the list is endless. But ‘social action’ is not something that can be boxed off; not a particular brand of Christian witness confined only to people with certain callings or inclinations, rather it encompasses our ways of living in the world. And as such it takes us beyond one-to-one relationships – though, of course, these too are ‘social’ – to our role in wider society.

Engagement towards transformation

Given that David Sheppard and Derek Worlock largely inspired T4CG, it is serendipitous that 2015 marks two anniversaries separately linked with them. First, it is 50 years this year since the end of the Second Vatican Council, which was such a major event in the history of the Roman Catholic Church. Vatican II took place at an influential time in Archbishop Derek Worlock’s formation, and he attended as Secretary to Cardinal William Godfrey. Second, in December 2015 it will be 30 years since the publication of Faith in the City, the report of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Commission on Urban Priority Areas, of which Bishop David Sheppard was vice chair. Both in different ways were landmarks. Vatican II was concerned with the fitness of the Roman Catholic Church for its engagement in today’s world. The purpose of the Council was to equip the Church to transform the modern world, though this was sometimes mistakenly interpreted as ‘adapting the Church to the modern world by making it more like the modern world’ (Ivereigh 2014, p. 90). Faith in the City was prompted by what was happening in England’s inner cities and on outer housing estates. Concern that had been mounting for some time was brought to a head by the disorders in different cities in the summer of 1981 and again in 1985. The report raised questions about the impact of public policies on urban priority areas (UPAs) but it also drew attention to aspects of church life that were seen as a recipe for alienation between the Church of England and people living in UPAs. The dual focus was important: ‘Only when the church is serious about setting its own house in order can it call on the state to do justly and love mercy’ (Forrester 1989, p. 86).

What does it mean for Christians and the Church to ‘do justly, and to love mercy’ (Micah 6.8 KJV) and to have the integrity to call on others to do likewise? The rest of this book seeks to examine these questions. Chapter 2 continues this introductory section by giving a brief introduction to the common good. The following four chapters look at different dimensions of how Christians pursue the common good and the nature of their collaboration: trends in ecumenism today, aspects of church involvement in the world, examples of social action and the task of speaking out in public life. The final chapter brings together the various threads and poses questions that I hope might continue this ‘conversation’.

2

Common Good:

Conversation and Transformation

A current concern

Although Christian teaching can give no policy prescriptions, it can provide values and principles to guide us as well as giving the motive force for change. The concept of the common good is closely linked with that of social justice. It has been especially prominent in Roman Catholic teaching … Such a guiding concept is clearly open to differing interpretations and its application must inevitably be modified in relation to historical and cultural circumstances. [But] it articulates a challenge which must always be faced.

Hilary Russell 1995, pp. 264–5

Since I wrote that passage 20 years ago, the idea of the common good has come into much wider use and not just among Roman Catholics or even just among Christians. The idea of the common good extends beyond faith groups to secular bodies. Wherever and whenever people are critical of the status quo and searching for alternatives, they need some binding concept that can help shape their vision and frame their thinking. A recent example was when, in 2013, a group of civil society organizations sent out a Call to Action for the Common Good addressed to the voluntary, public and private sectors and proposed a national debate to stimulate people to apply the principles within their organizations and within their sphere of influence. It came out of a wish to develop a more hopeful national story of change to address many of the big challenges faced across the country. Two seminars and a report followed in 2014. It continued to engage change makers across the sectors in order to define common good principles more sharply and find practical applications.

Steve Wyler asks what it would mean to work together for the common good. It is not simply a matter of combining common sense and good management to tackle a shared problem, or of better co-operation, reducing ‘silo’ working or building alliances. Vested interests, inertia and obstruction all make it more difficult. And there are hard questions about who decides priorities, how people with conflicting interests can work together and who will be included.

Can common good be accomplished from on high, or does it require a local people-sized community approach? The common good reveals itself as something which must be deeply contested, subjected to deliberative debate, if it is to mean anything worthwhile. (Wyler 2014, p. 41)

However, when people do work together for the common good it can be intensely liberating.

Power and ownership and risk and reward are distributed more widely, trust and friendships are built, new forms of solidarity emerge. And at the centre of this, as Catholic social teaching asserts, is always the quality of relationships between people and the commitments they are prepared to make to each other. Like myself, you don’t have to be a Catholic, or religious at all, to realize that this could be quite important. (Wyler 2014, p. 41)

This secular view underlines that the common good does not happen of itself, rather it has to be made and continually remade and is not something that can be imposed by an elite, however well-meaning. How then can people-powered change be brought about? This chapter seeks to explore some of the concepts that underpin the idea of the common good; subsequent ones examine ways it may be pursued.

What are the key ingredients of the common good?

The common good challenges us to address the fundamental, and essentially religious, question of what it means t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- 1 Beginnings

- 2 Common Good: Conversation and Transformation

- 3 ‘More Together, Less Apart’: Ecumenism Today

- 4 A Church Shaped by the Periphery

- 5 Who is My Neighbour?

- 6 Voices in the Public Square

- 7 Doing Justice to Our Faith?

- Bibliography

- Copyright