eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

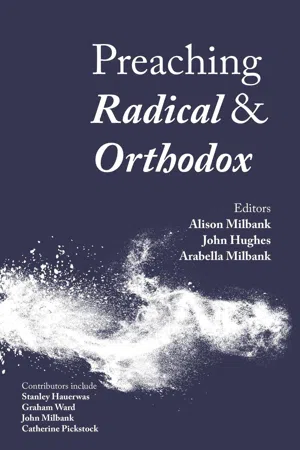

Preaching Radical and Orthodox

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Preaching Radical and Orthodox

About this book

Since its beginning in the 1990s, Radical Orthodoxy has become perhaps the most influential, and certainly the most controversial, movement in contemporary theology. This book offers an introduction to the Radical Orthodox sensibility through sermons preached by some of those most prominent figures in radical orthodoxy. Accessible, challenging and varied, the sermons together help to suggest what Radical Orthodoxy might mean in practice. Contributors include Andrew Davison, John Milbank, John Inge, Catherine Pickstock, Martin Warner, Graham Ward and Stanley Hauerwas

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Preaching Radical and Orthodox by Alison Milbank, John Hughes, Arabella Milbank, Alison Milbank,John Hughes,Arabella Milbank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Pratiche e rituali cristiani. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

V

For the Time Being:

Trinity Season and Christian Lives

Ordinary or ordered time turns attention to the Christian living out of the life of Christ, once the cycle of mimetic imitation of his earthly life opens out to the Feast of Corpus Christi and beyond. As a day of ‘Thanksgiving for Holy Communion’, Corpus Christi has again been owned by the Anglican Church, but its particular richness comes from the idea of ourselves as taken up with the elements into the transformative act of God in the sacrament, so that we as a body become the body of Christ. The communal nature of our life in Christ is central to this feast and to the saints’ days, which adorn this time, leading up to All Saints. In our introduction, we were unrepentant about the sometimes legendary developments of the lives of holy men and women, because such lives are generative of faith and further story. We still need St George to point out the dragons of want and greed, and tell us to fight them in society and in our own souls. The holy angels remind us that we are not God’s only creation, and that the world is charged with his love and knowledge, mediated to us through hidden powers.

Ecological concerns, as well as the rise of neo-paganism, have also drawn the Church back to the cycle of the agricultural year, upon which we all depend, and in which preaching can help to bring out the theological richness of Lammas and Harvest, and the challenge to our greed and injustice.

Our final section offers examples of sermons to accompany occasional offices and rites of passage. They reveal how the personal opens to the ecclesial, and how a life, lay or clerical, becomes exemplary and generative. This whole section is inflected by the theology of gift, which is a central feature of radically orthodox thought. In contrast to much gift theory, we stress not only the originating gift of God but its call for response and being taken up as gift and giver in acts of reciprocal exchange.

Preaching itself is never an originating act by the one speaking, but a response to the divine Spirit whose gifts make possible our speech. It aims to empower the people of God to respond to the Word heard in our words, and to be formed by the Spirit into active receivers, who themselves will share those gifts with others. Thomas Aquinas believed that we are made in the image of God as the one who gives life and freedom, so that we too may give life and freedom to that which we make. May our words too share that generative generosity, to fly from us, to be shaped and remade in the thoughts and actions of others.

Consume and Be Consumed

Feast of Corpus Christi

St Michael’s Church, Abingdon

John 6.47–52

THE REVD DR GREGORY PLATTEN

Last December saw the World Mince Pie Eating Competition, held at Wookey Hole in Somerset. The winner was a surprisingly diminutive young girl – Sonya Thomas – who consumed a record 46 mince pies in under ten minutes. I later worked out that’s an incredible 11,500 calories in ten minutes. If you are interested, that is six days’ worth of energy for the average female, all eaten in under ten minutes.

Calories are, of course, the scientific measurement of energy. At this Eucharist tonight, though, here in Abingdon, we are to eat food that, superficially, contains only a tiny few calories, and yet it has within it the raw energy of God. This bread and wine is indeed the very leaven of immortality. Thanksgiving for Holy Communion, therefore, is not thanking God for the gift of a service, weekly or daily enjoyed. It is, rather, thanksgiving for God’s gift of himself in his enfleshed Son; thanksgiving for his incarnation, for Jesus, through whom he has led us to share in the divine world.

The Feast of Corpus Christi emerged in the mediaeval period. Of course, the other great day when we remember the eucharistic foundations of our faith is Maundy Thursday. We recall the final supper of Christ with his friends in an upper room, hidden away from the anger of resentful doubters. Yet it is not possible to celebrate with true elation and ecstasy when the following day we remember the goring passion of our Lord on Good Friday. It was a rather persistent nun, one Juliana of Liège, who received mystical visions in which God had suggested that there ought to be a feast day for the Eucharist. After lengthy petitioning, she persuaded an influential local Dominican, the Archdeacon of Liège and the Bishop to introduce a grand local feast purely for the ‘Mass’ (such was the independence of bishops in those days in the Church of Rome) in 1246. Later on, following claims of a miracle involving a consecrated chalice of Christ’s blood, the same local archdeacon (one Jacques Pantalaéon) who, now made Pope Urban IV, finally decided that Corpus Christi, the body of Christ, should be a feast celebrated throughout the Church. That was in 1264.

We may not call it Corpus Christi in Anglican speak, just as we prefer Communion or Eucharist to Mass, some even drearily limiting it to the ‘Lord’s Supper’, which makes it sound like a special at the local Harvester. And yet, despite our Anglican reserve, it is quite right and proper that Anglicans celebrate our Lord’s great and simple command uttered in the upper room, ‘do this in remembrance of me’; those words are still followed in most churches and in most lands throughout the world.

This is mysterious and mystical, for this is not simply a set of words and actions; this is a feast that brings us into God’s nearer presence, to be participants in the divine life. Let us never forget how scandalous and extraordinary the gospel words of Christ must have sounded to the ears of those who first heard, when he calls himself the ‘bread of life’:

Very truly, I tell you, whoever believes has eternal life. I am the bread of life. Your ancestors ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. This is the bread that comes down from heaven, so that one may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live forever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh. (John 6.47–51)

There is no currency in the words of those who seek to soften this message, for it is stark and unnerving, the sundering of the divisions between earth and heaven. There is the physical and there is the spiritual; the boundaries between each are firmly drawn. That is, until Christ. Suddenly, what is divine, above and beyond, breaks in. Suddenly that which is intangible and ‘of the soul’ has cut through the thin veil and become physical incarne, there in meat, in flesh. In Christ, there is no nature and supernature; all is one cosmos, one whole. It is his flesh that he offers for our food and for our salvation. That is at the heart of the Eucharist and Communion. As the hymn goes: ‘types and shadows have their ending; for the newer rite is here’.

We eat Christ, we actually eat him, and take him into ourselves. But it is not cannibalism. Cannibalism is eating another fellow human; to eat Christ is to take God into ourselves. And here is when we need to worship with awe the mystery at the heart of the Eucharist. Christ promises us, as he did to Paul and his other earliest followers, that in bread broken and shared, in wine blessed and drunk from the cup, he is here with us. God transforms himself, through his Son, so that he can be as one with us, bone of our bone, flesh of our flesh, as close to us as the blood in our veins.

Lives have been lost, churches torn apart trying to define this great and tremendous mystery, hours spent trying to describe the technical details. Some have bought into the Aristotelian terms of transubstantiation, while others preferred the reformed memorialism of Zwingli. These extremes have rather missed the point. That bread becomes body and wine becomes blood is no problem to be solved, rather it is a mystery to be adored and praised. For it is this extraordinary transformation that means we take into ourselves, into our bodies, the body of Christ. Christ is physically incorporated within us; and through his dwelling within us, we are sanctified, drawn up inescapably into the divine. And as each is united with Christ, we are all united as one. This is communion by consumption. St John Chrysostom, in a homily on this same gospel passage, wrote:

We become one Body, and ‘members of His flesh and His bones’. (Eph. 5.30). Let the initiated follow what I say. In order then that we may become this not by love only, but in very deed, let us be blended into that flesh … He hath mixed up Himself with us; He hath kneaded up His body with ours, that we might be a certain One Thing, like a body joined to a head.20

We give thanks for the Eucharist, because the Eucharist is itself the giving thanks. In this service, word and action unite the divided parties of the world kneeling at one rail, bonded by one bread and body. At the same time earth and heaven unite too, witnessing the thin veil lifted. In this service, we are gathered up into the incarnation and redemption of Christ. This is no re-enactment, nor replay. This is none other than a foretaste of the heavenly banquet and we are fed with resurrection food.

Call it Mass, call it Communion, call it the Eucharist if you will. For me, they will always be known as the Holy Mysteries. For what can be more mysterious than the fact that the one we consume each time we meet together to give thanks is the very one that consumes us utterly, enfolding us in love, and giving us abundant life beyond decay and death. This truly is a fascinating and awesome mystery.

Note

20 St John Chrysostom, Homily 46 in 2004, Homilies on St John, trans. Philip Schaff, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series I, 14 vols, Peabody MA: Hendrickson, XIV, p. 166.

The Sound of Silence

First Sunday of Trinity

Church of the Holy Family, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

1 Kings 19.1–15; Psalms 42 and 43; Galatians 3.23–29; Luke

8. 26–39

STANLEY HAUERWAS

There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. And if you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to the promise (Gal. 3.28–29).

‘Finally,’ like me, you have to be thinking, ‘finally’! Finally we have a Paul that does not embarrass us. We have had to struggle with Paul’s seeming indifference to slavery; we have cringed at some of his judgements about the place of women in the Church; we have had to put up with his judgemental attitude about sex; but now it seems we have a Paul with whom we share some fundamental convictions.

After all, what could be more precious to us than the democratic commitment to treat all people equally? We want everyone to be treated fairly. We want to be treated fairly. Not only at work and home, but also in church. The Church accordingly should be inclusive, excluding no one. In this passage from Galatians Paul seems to be on the side of equal treatment. He finally got one right.

There is just one problem with our attempt to read Paul as an advocate of democratic egalitarianism. As much as we would like to think that Paul is finally on the right side of history, I am afraid that reading this text as an underwriting of egalitarian practice is not going to work. Paul does not say Jew or Greek, slave or free, male or female are to be treated equally. Rather he says that all who make up the Church in Galatia, and it is the Church to which he refers, are one in Christ Jesus. It seems that Jew and Greek, slave and free, male and female have been given a new identity more fundamental than whether they are a Jew, slave or free. In so far as they now are in the Church they are all one in Christ.

For Paul our unity in Christ seems to trump equality. Let me suggest that this is not necessarily bad news for us, because one of the problems with strong egalitarianism is how it can wash out difference. In truth, most of us do not want to be treated like everyone else because we are not simply anyone. Whatever defeats and victories have constituted our lives they are our defeats and victories and they make us who we are. We do not want to be treated equally if that means the history that has made us who we are must be ignored. For example, I think being a Texan is one of the determinative ontological categories of existence. I would never say I just happen to be a Texan because being a Texan, particularly in North Carolina, is a difference I am not about to give up in the hope of being treated fairly.

But what does it mean to be ‘one in Christ Jesus’? Some seem to think being one in Christ means Christians must be in agreement about matters that matter, and especially about the beliefs that make us Christian. The problem with that understanding is that there has been no time in the history of the Church when Christians have been in agreement about what makes us Christians. To be sure, hard-won consensus has from time to time been achieved, but usually the consensus sets the boundaries for the ongoing arguments we need in order to discern what we do not believe.

This disagreement is not necessarily the result of some Christians holding mistaken beliefs about the faith. We are a people scattered around the world who discover different ways of being Christian, given the challenges of particular contexts and times in which we find ourselves. If we were poor we might, for example, better understand the role of Mary in the piety of many that identify themselves as Roman Catholics.

If unity was a matter of agreement about all matters that matter, it clearly would be a condition that cannot be met. We certainly cannot meet the demand here at Holy Family. For example, I happen to know some of you are fans of the New York Yankees. Clearly we have deep disagreements that will not be easily resolved. So it surely cannot be the case our unity in Christ Jesus is a unity that depends on our being in agreement about all matters that matter.

There is another way to construe what it might mean to be one in Christ Jesus that I think is as problematic as the idea that our unity should be determined by our being a people who share common judgements about what makes us Christian. Some, for example, seem to think that unity is to be found in our regard for one another. We are united because we are a people who care about one another. Some even use the language of love to characterize what it means for us to be united in Christ.

The problem with that way of construing our unity is it is plainly false. We do not know one another well enough to know if we like, much less love, one another. Of course it is true that you do not have to like someone to love them, but I suspect that, like me, you tend to distrust anyone who claims to love you but does not know you. If love, as Iris Murdoch suggests, is the nonviolent apprehension of the other as other, then you cannot love everyone in general. The love that matters is that which does not fear difference. Christians are, of course, obligated to love one another and such love may certainly have a role to play in our being one in Christ Jesus. But that does not seem to be what Paul means in this letter to the Galatians.

Paul seems to think that what it means for us to be one in Christ Jesus is a more determinative reality than our personal relations with one another make possible. Indeed when unity is construed in terms of our ability to put up with one another the results can be quite oppressive. For the demand that we must like or even love one another can turn out to be a formula for a church in which everyone quite literally is alike. A friendly church can be a church that fears difference. As much as we might regret it, I suspect it remains true tha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Introduction

- I. Reclaiming Time: Advent

- II. Preaching Paradox: Christmas to Candlema

- III. Unfolding the Story: Lent to Easter Sunday

- IV. Real Resurrection: Eastertide to Trinity Sunday

- V. For the Time Being: Trinity Season and Christian Lives

- Further Reading

- Copyright