- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

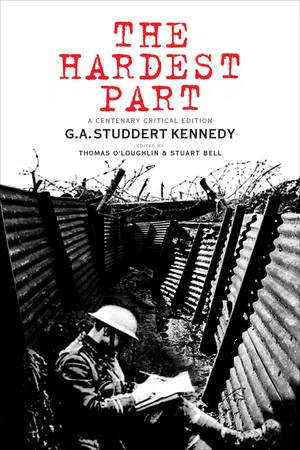

The Hardest Part

A Centenary Critical Edition

About this book

Stark, moving but with glimmers of humour amongst the wreckage, "The Hardest Part" asks perhaps the hardest question of all when faced with the horrors of the 1st World War - where was God to be found in the carnage of the western front? Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy's answer, that through the cross God shares in human suffering rather than being a 'passionate potentate' looking down unmoved by death, injury and destruction on an immense scale, was, and still is, revolutionary.Marking the centenary both of the end of the First World War and the original publication of The Hardest Part, this new critical edition contains a contextual introduction, a brief biography of Studdert Kennedy, annotated bibliography and the full text of the first edition of the book, with explanatory notes.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

| Draft manuscript of chapter 3 | The published text |

| In a German concrete shelter. Time, 2.30 a.m. All night we had been making unsuccessful attempts to bring down some wounded men from the line. We could not get them through the shelling. One was blown to pieces as he lay on his stretcher. | |

| I wonder how much this beastly thing would stand. I guess that it would come in with a 5.9. That’s a near ’un. Somebody light the candle. I wish we could have got some of them. It was rotten missing all three, and that poor chap all blown to bits. To be wounded is bad enough, but to [be] left out two days and then blown up in the end, that’s the limit. | I wonder how much this beastly shanty would stand. I guess it would come in on us with a direct hit, and it looks like getting one soon. Lord, that was near it. Here, somebody light that candle again. I wish we could have got those chaps down. It was murder to attempt it though. That poor lad, all blown to bits – I wonder who he was. God, it’s awful. |

| The glory of war, what utter blather it all is. That chap in the “Soldiers Three” was about right: Says Mooney, I declare, The death is everywhere; But the glory never seems to be about. War is only glorious when you buy it in the Daily Mail and enjoy it at the breakfast-table. It goes splendidly with bacon and eggs. Real war is the final limit of damnable brutality, and that’s all there is in it. It’s about the silliest, filthiest, most inhumanly fatuous thing that ever happened. It makes the whole universe seem like a mad muddle. One feels that all talk of order and meaning in life is insane sentimentality. | |

| What a perfectly filthy business this war is. And it is not as if this were the only war. It is not as if war were really abnormal or extraordinary. In England just before the war, we’d got to think it was. We read the [G]reat Illusion and we said that war was an anachronism in a civilised world. We’d got past it. It would not, could not, come again. I still think it is The Great Illusion. I still think it’s an anachronism in a civilised world. But it has come again all right. | It’s not as if this were the only war. It’s not as if war were extraordinary or abnormal. It’s as ordinary and as normal as man. In the days of peace before this war we had come to think of it as abnormal and extraordinary. We had read The Great Illusion, and were all agreed that war was an anachronism in a civilised world. We had got past it. It was primitive, and would not, could not, come again on a large scale. It is “The Great Illusion” right enough, and it is an anachronism in a civilised world. We ought to have got past it; but we haven’t. It has come again on a gigantic scale. |

| Shut that door the light can be seen. | I say, keep that door shut; the light can be seen. I believe they are right on to this place. There was a German sausage up all day just opposite, and they must have spotted movement hereabouts this morning. There it goes again. Snakes, that’s my foot you’re standing on. Anybody hurt? Right-o, light the candle. It’s no fun smoking in the dark. |

| And war is not really abnormal or extraordinary. It’s as normal and as ordinary as sin. The history of man is the history of War as far back as we can trace it. It’s all wars. Calvary made no difference to that. Christ could not kill the God of War. Men simply turned and waged them in His name. The head of the Church made wars. There’s a war on now – and there have not been in the history of | Yes, war has come again all right. It’s the rule with man, not the exception. The history of man is the history of war as far back as we can trace it. Christ made no difference to that. There never has been peace on earth. Christ could not conquer war. He gave us chivalry, and produced the sporting soldier; but even that seems dead. Chivalry and poison gas don’t go well together. Christ |

| the world three consecutive years when their1 has not been a war on somewhere. That much the militarist historians have got in their favour. Progress has been everywhere and at all times accompanied by war. That is not a theory that’s a fact – as certain as my mother’s mangle. As the longwinded Johnnies would put it Progress and War are invariably concomitant Phenomena in human history and what is it that chap on the train said Invariable concomitance is incompatible with complete causal independence.2 Which means that if war and progress always go together, either war must cause progress or progress must cause war, or they must act and interact like drink and poverty. It sounds to durn reasonable for words. But I’m not sure it’s true. | Himself was turned into a warrior and led men out to war. Few wars have been so fierce and so prolonged as the so-called religious wars. Of course a deeper study of history reveals the fact that they were not really religious wars. Religion was not the real, but only the apparent cause of them. They were just political and commercial struggles waged under the cloak of religion. I don’t believe that religion had anything to do with the Inquisition, it was a political business throughout. Still these struggles, with all their sordid brutalities, proved Christ helpless against the God of War. He is helpless still. God is helpless to prevent war, or else He wills it and approves of it. There is the alternative. You pay your money and you take your choice. |

| Christians in the past have taken the second alternative, and have stoutly declared that God wills war. They have quoted Christ as saying that He came not to bring peace upon the earth, but a sword. Bernhardi did that quite lately. Luther did it too, I believe. If you cling to God’s absolute omnipotence, you must do it. If God is absolutely omnipotent, He must will war, since war is and always has been the commonplace of history. Men are driven to the conclusion that war is the will of the Almighty God. | |

| It’s got an enormous lot to say for itself. I guess Mr Treitsch[k]e has said it about as well as it can be said. He has the whole Darwinian theory of evolution as expounded by Ha[e]c[k]el behind the struggle for existence and the survival of the fittest. He can go back to the amoeba and show that the struggle has been the cause of progress right away down – or at any rate that they have always gone together. He can bang away at Christianity with a battery of perfect reason and perfect logic. The philosophy of militarism like the logic of determinism is perfect – it is the most impressive intellectual edifice ever constructed. And if God is Almighty – if the way the world has grown has been in continual accordance with his will [–] I don’t see how we can escape it. It is irresistible. God is on the side | |

| of the Big Battalions, and the man or nation who can conquer is the chosen of God. Might is right – and war is God’s method – God’s appointed medicine for the healing of the nation’s ills. The militarist philosophy of history is absolutely sound – and Prussian action is practice is the logical outcome of Prussian theory. The one duty of the state is to be strong and he who will not face that fact must keep his hands off politics. The Prussian Kaiser is not a hypocrite when he speaks of God as his ally – his chief supporter – he is not a hypocrite – he is perfectly sinie [sic – meaning ‘sincere’], perfectly logical – and perfectly damnable Prussian frightfulness also is perfectly logical – perfectly sincere – and perfectly damnable. | |

| We cry out against it – I cry out against it – I hate it – I am ready – quite ready to die – fighting it. That’s why I’m here. I’m not here because I’m a patriot. I don’t care a hang for England apart from what I believe England stands for. I’ve not got an ounce of loyal sentiment in me. I respect King George because I believe him to be an honest – painstaking – public servant – and a suitable head of the Anglo Saxon republic of free nations. If he were not a decent man – and good public servant – I would want to kick him ... |

Table of contents

- Copyright information

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Man, the Padre and the Theologian

- Gone and Almost Forgotten: The Reception of The Hardest Part

- Original Text

- Dedication

- Preface

- Author’s Introduction

- Map of the Battle of Messines Ridge.

- I. What is God like?

- II. God in Nature

- III. God in History

- IV. God in the Bible

- A chaplain’s grave

- V. God and Democracy

- VI. God and Prayer

- VII. God and the Sacrament

- VIII. God and the Church

- IX. God and the Life Eternal

- Postscript

- A crucifix

- Appendix 1: An Early Manuscript Version of Chapter 3

- Appendix 2: Author’s Preface to New Edition, 1925

- Appendix 3: Studdert Kennedy’s Poems on Divine Suffering

- References and Further Reading

- Books about Studdert Kennedy