This book is available to read until 4th February, 2026

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 4 Feb |Learn more

About this book

Over the last five years, transgender people have seemed to burst into the public eye: Time declared 2014 a 'trans tipping point', while American Vogue named 2015 'the year of trans visibility'. From our television screens to the ballot box, transgender people have suddenly become part of the zeitgeist.

This apparently overnight emergence, though, is just the latest stage in a long and varied history. The renown of Paris Lees and Hari Nef has its roots in the efforts of those who struggled for equality before them, but were met with indifference – and often outright hostility – from mainstream society.

Trans Britain chronicles this journey in the words of those who were there to witness a marginalised community grow into the visible phenomenon we recognise today: activists, film-makers, broadcasters, parents, an actress, a rock musician and a priest, among many others.

Here is everything you always wanted to know about the background of the trans community, but never knew how to ask.

This apparently overnight emergence, though, is just the latest stage in a long and varied history. The renown of Paris Lees and Hari Nef has its roots in the efforts of those who struggled for equality before them, but were met with indifference – and often outright hostility – from mainstream society.

Trans Britain chronicles this journey in the words of those who were there to witness a marginalised community grow into the visible phenomenon we recognise today: activists, film-makers, broadcasters, parents, an actress, a rock musician and a priest, among many others.

Here is everything you always wanted to know about the background of the trans community, but never knew how to ask.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Trans Britain by Ms Christine Burns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Survival

My childhood was spent every evening praying that God would put right this terrible mistake and that the following morning I would wake up a proper girl.

Carol Steele, chapter 3

Is There Anyone Else Like Me?

The sixties began in much the same way as the fifties had ended as far as trans people were concerned. It was a time when the chances are that a person feeling like Michael Dillon or Roberta Cowell might not even know there were other people like themselves.

There was no Internet. There was nowhere to find out information, unless you had access to a medical library. What you found in such a library would not be very encouraging. Biographies about trans people were many years away. Conundrum, the first British mainstream trans autobiography, by historian and writer Jan Morris, would not appear until 1974. The most likely way for a newcomer to hear about trans people before that was through the salacious revelations that were becoming the stock-in-trade of the popular Sunday newspapers. The outing of Michael Dillon in 1958 had been pursued without any regard to the effect that it might have upon him, or anyone like him. The same was true when April Ashley’s story was splashed across a front page in 1961.

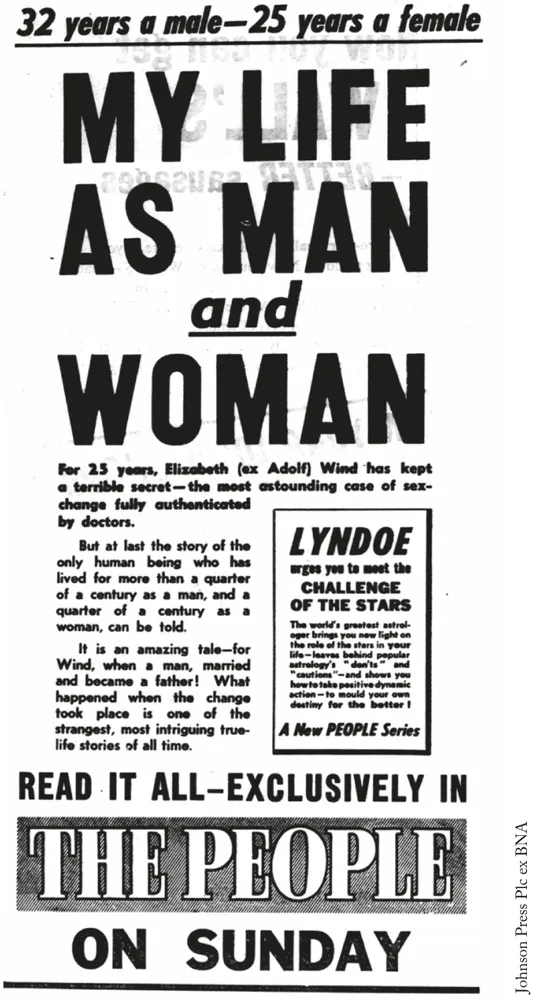

Not every newspaper story in those days was an ‘outing’. It is said that Roberta Cowell sold her story to the Picture Post in March 1954 to derive some income for herself – perhaps noting how Christine Jorgensen was monetising her status over in the United States. That is far from the norm, however. ‘Outing’ is more commonplace, and if the choice is between being splashed without consent or agreeing to cooperate, exert a little influence over the copy and be paid, most people would probably cut their losses. What we do know is that such stories were not one-offs. In what looks like a ‘me too’ story, the Sunday People were advertising in January 1955 a confessional feature about someone called Liz Wind.

‘Me too’ for the Sunday People? An advertisement from January 1955 for a newspaper feature bearing a strong resemblance to the Picture Post’s story about Roberta Cowell.

If you harboured trans feelings in the fifties and early sixties, this was the most accessible way you could possibly find out that there was anyone else remotely similar. And it wasn’t high-quality information. Roberta Cowell had constructed a fiction about her background – the claim that she had been born with a physical intersex condition – in order to enable Sir Harold Gillies to operate on her without censure. The claim also played a part in her bid to have her birth certificate altered. Michael Dillon’s clinical history was portrayed in a similar way. Those transitions reported in the 1930s – Mark Weston and Mark Woods, for instance – were reported as magically spontaneous natural changes of sex. And if you clung on to every breathless word about April Ashley in the Sunday papers then you would have been led to believe that in order to pursue gender reassignment surgery without the supposed hand of God then you would have to get a plane ticket to Casablanca. Even a decade later, in Jan Morris’s 1974 autobiography, that was the clear implication.

This was also a world where homosexuality was still completely illegal, and trans people – whether occasional cross-dressers or those who fitted the clinical definition of transsexual – were seen as a sort of subcategory.

The Sexual Offences Act was passed in 1967 after lengthy and tortuous public and parliamentary debate. The act legalised homosexual contact between two men over the age of twenty-one in private, although Stonewall co-founder Lord Michael Cashman CBE has pointed out how, in practice, the early years after that act was passed saw anyone perceived as gay being harassed more rather than less. James Anderton, who served as chief constable of Greater Manchester from 1976 to 1991, was notorious for policies that seemed to target the city’s sexual minorities – cross-dressers and transsexual people included. In the 1980s he famously accused homosexuals, drug addicts and prostitutes – all part of the HIV/AIDS epidemic – of ‘swirling in a human cesspit of their own making’. The words were not directly aimed at cross-dressers or transsexuals, but the general perception that such people were gay or otherwise seeking men for paid sex meant that trans people throughout that era perceived that the threat applied to them too. A common assumption about transsexual women at that time was that they transitioned just in order to access sex with men. Even some gay men bought into that narrative in those days, deciding that trans women were simply gay men who had gone too far or were looking to make their desire for men more acceptable.

Incidentally, the lumping together of transvestites (episodic cross-dressers) and transsexual people (permanent transitioners) may offend some trans readers. Many transsexual people have spent their lives trying to explain to strangers that these two like-sounding terms for superficially similar people mean a world of difference – even though trans people of all stripes would at one time casually use the expression ‘transvestites and transsexuals’ (TV/TS in the vernacular) as though it were a single concept.

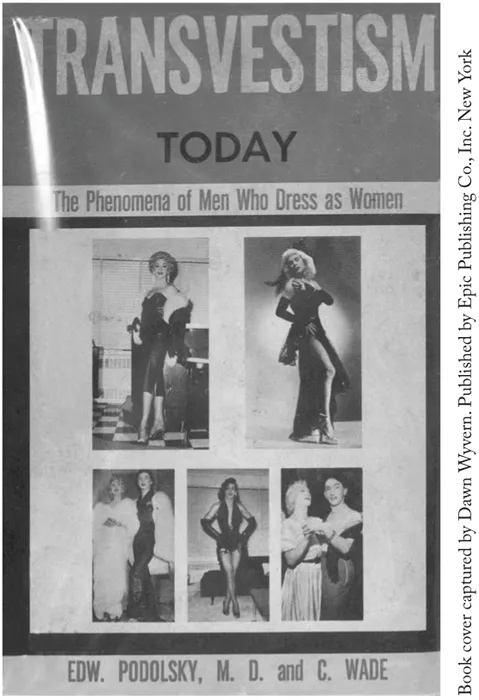

An American medical textbook from 1960. A note on the rear cover instructs that this was ‘only to be sold to members of the medical profession’. The book is ostensibly about cross-dressing but the author casually labels many obviously transsexual women as ‘Professional Female Impersonators’ and reduces discussion of transsexualism as a distinct phenomenon to a seven-page chapter.

This book is mostly about the people who change permanently, but we have to talk about cross-dressers too – not only because they are part of the ‘trans umbrella’ but also because the two were deeply co-dependent for a while. Also, some transsexual people pass through a period of experimentation to find who they really are. Trying out the possibility that you might be happy just cross-dressing now and then sounds a whole lot less frightening than acknowledging the need to permanently transition. It’s only through experimentation in that way that some people may conclude that there really is no simpler alternative to the realisation that they need to transition permanently.

The main point about the early sixties was that trans people had nowhere of their own to go; nothing of theirs to belong to. If they wanted somewhere safe – transvestite or transsexual – then the only places available were those where the gays and lesbians and drag queens hung out. Some people were happy with that, some were not.

Dr Tracie O’Keefe is a lesbian transsexual woman who remembers that period well. She would later go on to marry her cisgender (non-trans) female partner Katrina in 1998 – an officially sanctioned same-sex marriage – because, even though she had transitioned almost thirty years earlier in 1970, the law at that time still regarded her as a man. In the sixties she liked to party:

In the late sixties we used to go to a pub in Peckham that had drag shows. I remember going there on the back of my boyfriend’s Lambretta at fourteen years old with my feather cut hair do and my Parka coat thinking I was way cool. We would also go to the Black Cap pub in Camden town. With enough make-up I could pass for older. They had the funniest drag in London, with Jean Fredricks and Mrs Shufflewick. However it was always tricky being trans and going into gay pubs and clubs because you knew the staff might ask you to leave at any time, telling you trans people were not allowed. In Chelsea it was safe to go to the Queen’s Head – or was it the King’s Head? – anyway it was full of queens. Ron Storm used to hold balls in East London in the seventies and Andrew Logan ran the Alternative Miss World too. Trans people who were part of the fashion and music set would also socialise in clubs like the Sombrero where I would go with my friend Ossie Clarke the designer in Kensington High Street. Sometimes Amanda Lear would come down. In the seventies you could go to the Vauxhall Tavern, run by a fabulous woman called Peggy who was the salt of the earth and welcomed everyone.

Partying is all very well, but sometimes people needed support and information. As we’ve seen, in the early sixties the only public information about trans people seemed to be in the tabloids – conveying the impression that trans people were rare, shocking and needed to go to North Africa to get their ‘freakish’ changes.

The first big milestone in British trans history – the spark that arguably set in motion the chain of events that led to today’s very different world of confident, diverse, well-informed and articulate trans people – was when a scattered handful of pioneers came across one another and founded the first ever organisation to support and help people like themselves. And the inspiration for that came from across the Atlantic…

In the late 1950s a US pharmacist called Dr Virginia Prince (1912–2009) began a correspondence-based network for (primarily) transvestites. The organisation she set up had the trappings of a college sorority. The name Phi Pi Epsilon was the Greek-lettered acronym for Full Personality Expression (FPE) and it was organised into geographic ‘chapters’. Members of the group received a periodic magazine called Transvestia, first published in 1960 by Prince’s own Chevalier Publications.

Prince had radical views (for the time) about her identity. She carved an alternative path between the classic understanding of transvestism and transsexualism, arguing that a person could transition permanently – live all the time as a woman, maybe even using hormones to develop breasts and curves – and yet do so without resort to genital reassignment surgery. It is not agreed whether she coined the term, but she undoubtedly popularised the word ‘transgender’ and it became initially attached to the idea of her middle-ground, non-operative way of transitioning. These days ‘transgender’ has acquired a much broader meaning and it is stressed to people seeking medical help that reassignment surgery is an option, not compulsory. The rise of a culture of non-binary expression in recent years only serves to reinforce the idea of options. Yet in the early sixties, Prince’s views were not universally welcomed.

Nevertheless, it was through international distribution of Prince’s magazine Transvestia that Phi Pi Epsilon indirectly encouraged the creation of the first support organisation for cross-dressers and transsexuals in Britain – the Beaumont Society – and, with it, sowed the seeds for a trans community where none had existed before.

Transvestia was stocked by some fringe outlets, such as London’s Soho bookshops. This is how Britons came to know about it and join FPE. Four European FPE members – Alga Campbell, Alice Purnell, Sylvia Carter and someone called Giselle – met through FPE’s contact system and set up a European Chapter of the American parent organisation. Later they went a step further, arranging to create a separate group, which they called the Beaumont Society (after the Chevalier d’Éon de Beaumont). They figured that this would sound innocuous to outsiders but carry meaning for those they wanted to reach.

The stated objectives of the new society, set up in 1966, were:

1. To provide information and education to the general public, the medical and legal professions on transvestism and to encourage research aimed at fuller understanding.

2. To provide transvestites with an opportunity for a social life together.

Note that these aims were couched in terms of transvestism and not transsexualism. Nevertheless, beggars can’t be choosers. Transsexual people on their own were (at least initially) too small in number to support...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- By the Same Author

- Contents

- Foreword by Professor Aaron Devor

- A Beginner’s Glossary

- Introduction by Christine Burns

- Part One Survival

- Is There Anyone Else Like Me? – Christine Burns

- 1 The Doctor Won’t See You Now – Adrienne Nash

- 2 1966 and All That: The History of Charing Cross Gender Identity Clinic – Dr Stuart Lorimer

- 3 The Formative Years – Carol Steele

- 4 Where Do the Mermaids Stand? – Margaret Griffiths

- 5 Sex, Gender and Rock ’n’ Roll – Kate Hutchinson

- 6 A Vicar’s Story – Rev. Christina Beardsley

- Part Two Activism

- A Question of Human Rights – Christine Burns

- 7 Taking to the Law – Mark Rees with the assistance of Katherine O’Donnell

- 8 The Parliamentarian – Dr Lynne Jones

- 9 The Press – Jane Fae

- 10 Film and Television – Annie Wallace

- 11 Section 28 and the Journey from the Gay Teachers’ Group to LGBT History Month – Professor Emeritus Sue Sanders of the Harvey Milk Institute with the assistance of Jeanne Nadeau

- 12 A Scottish History of Trans Equality Activism – James Morton

- Part Three Growth

- The Social Challenge – Christine Burns

- 13 The Trade Unions – Carola Towle

- 14 Gendered Intelligence – Dr Jay Stewart MBE

- 15 Non-Binary Identity – Meg-John Barker, Ben Vincent and Jos Twist

- 16 The Activist New Wave – Sarah Brown

- 17 Better Press and TV – Helen Belcher

- 18 Making History Today – Fox Fisher

- 19 A Very Modern Transition – Stephanie Hirst

- Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Index

- Supporters’ Names

- Copyright