eBook - ePub

Between Remembrance and Repair

Commemorating Racial Violence in Philadelphia, Mississippi

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Between Remembrance and Repair

Commemorating Racial Violence in Philadelphia, Mississippi

About this book

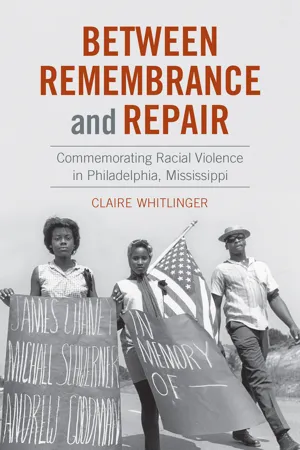

Few places are more notorious for civil rights–era violence than Philadelphia, Mississippi, the site of the 1964 “Mississippi Burning” murders. Yet in a striking turn of events, Philadelphia has become a beacon in Mississippi’s racial reckoning in the decades since. Claire Whitlinger investigates how this community came to acknowledge its past, offering significant insight into the social impacts of commemoration. Examining two commemorations around key anniversaries of the murders held in 1989 and 2004, Whitlinger shows the differences in how those events unfolded. She also charts how the 2004 commemoration offered a springboard for the trial of former Klan leader Edgar Ray Killen for his role in the 1964 murders, the 2006 passage of Mississippi’s Civil Rights/Human Rights education bill, and the initiation of the Mississippi Truth Project. In doing so, Whitlinger provides the first comprehensive account of these high profile events and expands our understanding of how commemorations both emerge out of and catalyze associated memory movements.

Threading a compelling story with theoretical insights, Whitlinger delivers a study that will help scholars, students, and activists alike better understand the dynamics of commemorating difficult pasts, commemorative practices in general, and the links between memory, race, and social change.

Threading a compelling story with theoretical insights, Whitlinger delivers a study that will help scholars, students, and activists alike better understand the dynamics of commemorating difficult pasts, commemorative practices in general, and the links between memory, race, and social change.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 A Philadelphia (Mississippi) Story

Remembering in Black and White

The sheer number of aphorisms about remembrance can make the subject seem almost trite. They include: “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting;”1 “History is written by the victors;”2 and “He who controls the past controls the future.”3 But encoded in these adages is an expression of a common experience and a general truth: that history and memory are embedded within systems of power—systems that privilege certain historical “facts” and relegate others to oblivion. The local memory of the 1964 murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner is no different, for while the contours of Philadelphia’s story are known, key elements remain obscured—elements that illuminate how the residents (black, white, and Choctaw) of Philadelphia and its surrounding county have reckoned with their racially charged past.

Most histories of Neshoba County provide only a cursory account of its commemorative practices. In general, they depict the twenty-five years following the murders as “the long silence,” a period during which the murders remained unacknowledged in any official capacity and local people maintained a conspiracy of silence even as the murders became memory.4 Describing the twenty-five years following the murders as “silent,” however, is not wholly accurate. It overlooks the vibrant commemorative landscape that was nurtured by Philadelphia’s and Neshoba County’s African American communities, sometimes putting them at great risk. As white residents largely avoided discussing what they often referred to as “the troubles” of 1964 in the decades following the murders, black churches erected monuments, hosted memorial services, and nourished protesters who marched in memory of the three civil rights activists. Philadelphia, then, was not silent about the murders. Rather, its long history of commemoration has been silenced by historical reconstructions that conflate the city’s history with the history of its white citizenry, a phenomenon that has been common throughout much of southern historiography.5

This sort of erasure is not specific to professional historians. Rather, it stems from a long-standing tendency to treat white history as synonymous with southern identity. Florence Mars, a member of one of Neshoba County’s most prominent white families, reflects on this in her 1977 memoir, Witness in Philadelphia: “As I was growing up, I learned how the South saw itself … southerners were white; Negroes were Negroes.”6 Furthermore, Mars remembers having been inculcated with a sense of white superiority. “White civilization of the South,” she recalled, “was one of the greatest in the history of the world. Negro culture,” alternately, “was primitive and greatly inferior.” Consequently, this prevailing metanarrative rendered invisible the contributions of African Americans to southern life and its recorded history.7

Acknowledging the commemorative activities of local African Americans thus casts new light on memory practices in Philadelphia and Neshoba County. It reveals two parallel mnemonic trajectories: one embedded within Philadelphia’s dominant white public sphere, and the other enacted within Philadelphia’s black counterpublic—a space where local African Americans and their allies preserved competing versions of the past. To understand these parallel mnemonic trajectories and their significance for Philadelphia’s community-wide commemorations in 1989 and 2004, one must understand the history of Neshoba County itself, for as Mars observes, “In Neshoba County, Mississippi, the basement of the past is not very deep. All mysteries of the present seem to be entangled in the total history of the county.”8

The Red-Clay Hills of Neshoba

The recorded history of Neshoba County begins in the 1830s, when white settlers from Georgia and the Carolinas descended on the red-clay hills that would become the twenty-four square miles that made up the county of Neshoba, the Choctaw word for wolf. Not far from Philadelphia lies a massive burial mound, Nanih Waiya, that contains the remains of some eighteen thousand Choctaw Indians who had long inhabited the sloping hills and swamps (called bogues in Choctaw) that would come to be dominated by white pioneers who sought to eke out a living in cotton after the U.S. government compelled the Choctaw to move to the Oklahoma Territory following the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1831. Not all the Choctaw submitted to this forced emigration, however. Some five thousand refused to relinquish their land, and these are the ancestors of the nearly four thousand Choctaw who reside in Neshoba County today and have been recognized as the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.9

By 1860, some thirty years after the county’s founding, there were roughly twenty-two white landowning families in the region, eighteen of which still had direct descendants there in 1960.10 There was little migration to or from Neshoba County during its history, a product of its remote location and hostile conditions: the same thick red clay that failed to yield the rich cotton crops of the Mississippi Delta made it difficult to traverse the county. As late as the 1940s, Mars recalls her daily rides with “Poppaw” to visit his tenants. Prudent investments had allowed her grandfather to become the largest landowner in the county. But on rainy days, the slippery, clotted clay was unmoved by Poppaw’s local status. “Except for a sprinkling of native gravel in the hillier sections of the county and the occasional sandy spot,” remembers Mars, “the roads were pure red clay, which, when they were wet,” caused wagons to slip or get bogged down. “The roads weren’t made for automobiles in those days,” Mars lamented, “though not many people had them anyway.”11

Indeed, it wasn’t until 1931 that the first road in the county was graveled, much later than was the case in counties whose seat stood between two major cities. Through the early twentieth century, transporting goods from Philadelphia, the Neshoba County seat since 1838, to Meridian, thirty-five miles to the east, could take up to three days, and receiving goods from Jackson via flatboat on the Pearl River could take upward of one month.12 Local merchants perhaps should have been more civic-minded about Neshoba’s isolation, but they benefited greatly from the limited outside competition and were instrumental in keeping the highways unpaved.13 In 1909, the editor of the county newspaper, the Neshoba Democrat, described the county in the early twentieth century as being “classed as one of the most under-developed and backwoods counties in the state.” “This impression,” he wrote, “went out over the country not on account of the barrenness of the soil or the ignorance of the citizenship but on account of the fact that we were without telegraph and railroad communication with the outside world.”14

The beginning of the twentieth century brought new hardships to the region but also new possibilities. The railroad, which finally arrived in Philadelphia in 1905, stimulated commerce. However, by then the boll weevil had destroyed much of the cotton crop, an additional blow to the land and its people—whose losses during the Civil War were still in living memory. As white farmers left for greener pastures, the racial demographics of the region shifted, and the already sparse population of the county became sparser still. In the 1940s, a white businessman sold small lots to black residents on credit. This further bolstered the population in the western portion of Philadelphia, which would come to be known as Independence Quarters,15 but here—as in most Mississippi towns at the time—“the other side of the tracks bespoke another universe.”16 Unlike the white part of town, with picturesque homes on avenues with idyllic names like Poplar, Independence Quarters had no sidewalks, no running water, no sewer system, and until the 1950s no garbage pickup—as well as no mail delivery until much later.17

Though the county’s whites prided themselves on having “good race relations,” the county was no stranger to racial violence and intimidation. The regional resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s18 led local Klansmen to burn crosses throughout the county. Residents of the county also seemed indifferent to due process. According to Willie Morris, during a four-year period there were thirty-three homicides, and only two culprits “paid their debt to society”—and they did it by hanging themselves in their jail cells.19 But local white leaders spoke out against the Klan and the climate it cultivated. In an open letter published in the Neshoba Democrat that took up nearly one-third of the front page, Ab DeWeese, who owned a prominent lumber company in the area, admonished the Klan: “I take the position that [the Klan] is acting in opposition to constitutional government. It assumes to indict, to represent the jurors, and to judge, and then to execute, and this power and right should come through the constitutional government. And furthermore, it acts behind a mask and does not out in the open.” Another white businessman regretted that “so many weak-kneed politicians and preachers had become intimidated to the point that they were afraid to express their honest convictions on the Klan issue.”20 Clayton Rand, the editor of the Neshoba Democrat since 1918, was equally dismayed. While viewing the Klan as having served a “good purpose” during Reconstruction, defending the South from “plunderers and brigands,” Rand described the 1920s Klan in his newspaper as “an outlaw organization going about its work behind masks and in clown suits.”21 The vocal public resistance to the Klan that was evident in the 1920s was notably missing in the 1960s.

The “Long, Hot Summer”

In 1964, the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce issued a promotional brochure describing Neshoba County as “a thriving community” of twenty-one thousand people—with six thousand residing in the county seat, Philadelphia—located “in the East Central part of the beautiful Magnolia state.”22 “The most outstanding attraction,” the brochure boasted, “is the friendly and hospitable people who make the area their home. A visitor to our community finds an old-fashioned welcome and a degree of friendliness that exists in no other place.” In addition to a “diversified” industrial base—milk, motors, and lumber—the chamber advertised the county’s new hospital, swimming pool, nine-hole golf course, and numerous lakes. “For the hunter,” it claimed, “Neshoba County is a paradise.”

This depiction of a cheerful, industrious county provides a stark contrast to the reputation it would have earned by the summer’s end. The summer of 1964 is often referred to as the “long, hot summer,” a phrase that describes not only Mississippi’s stifling summer climate but also the racial tensions that came to a boiling point during those particularly contentious months. Over the previous decade, private citizens and state actors had buttressed their defenses against so-called civil righters who threatened to dismantle Jim Crow segregation, but these invaders seemed to be gaining ground. Not even the citizens’ councils—local organizations founded in reaction to the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which mandated the desegregation of public schools at “all deliberate speed”—could stay the impending offensive planned by the Council of Federated Organizations.23 COFO, as it was known, became the umbrella organization coordinating the efforts of civil rights organizations operating in the state, primarily the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Such coordination became crucial when disagreements among the organizations threatened to destroy the fledgling Mississippi movement from within. Originally created before the 1961 Freedom Rides and revamped in 1962, COFO became the touchstone of civil rights activity in the state and a lightning rod for the animosity toward it.

Since 1954, the citizens’ councils had been the state’s self-appointed watchdogs, resisting educational content presented at public schools and universities that challenged segregation. A grassroots movement initiated by Robert Patterson in Indianola, Mississippi, and made up primarily of affluent white men, the councils sought to maintain school segregation without violence, earning them the moniker “Uptown Klan.”24 But they had other tools at their disposal. Within the first three months, the councils had twenty-five thousand dues-paying members, and they intimidated activists, people suspected of being activists, and those sympathetic to activists through a range of economic and political tactics such as boycotting businesses, firing employees, or revoking the leases of rental homes.25

Such treatment of civil ri...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figure, Graphs, and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. A Philadelphia (Mississippi) Story: Remembering in Black and White

- 2. From Countermemory to Collective Memory

- 3. Prosecuting Edgar Ray Killen

- 4. Legislating Civil and Human Rights Education

- 5. Commissioning Truth and Reconciliation

- 6. The Transformative Capacity of Commemorating Racial Violence: Comparing the 1989 and 2004 Commemorations

- 7. Commemorating Racial Violence as Intergroup Contact

- 8. Commemoration Is a Constant Struggle

- Epilogue: Fifty Years Forward

- Appendix A. On Methods

- Appendix B. Archival Collections

- Appendix C. List of Interviews

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Between Remembrance and Repair by Claire Whitlinger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.