eBook - ePub

Place Making

Developing Town Centers, Main Streets, and Urban Villages

- 305 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Place Making

Developing Town Centers, Main Streets, and Urban Villages

About this book

Addressing one of the hottest trends in real estate—the development of town centers and urban villages with mixed uses in pedestrian-friendly settings—this book will help navigate through the unique design and development issues and reveal how to make all elements work together.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Place Making by Charles C. Bohl,Charles C. Bohl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Place-Making Trend

There’s no there, there.—GERTRUDE STEIN, Everybody’s Autobiography

Too much of anything is too much for me.

In sharp contrast to the suburban character of the surrounding neighborhoods and to the sprawling strip development that ripples along the fringes of Gainesville, Florida, Haile Village Center offers narrow streets and alleys, apartments and townhouses above shops and offices, a meetinghouse, and a village green. Why would the developer, Robert Kramer, have undertaken the challenging, long-term process of planning, designing, and building a mixed-use village center with a traditional layout and design? When several possible reasons for undertaking such a project were posed to him—such as the growing desire to provide suburban towns with an identity and a sense of place; to create more walkable neighborhoods; and to develop “smarter,” more sustainable communities, he smiled and replied, “I thought the reason was to make money.”

Morning in Haile Village Center, Gainesville, Florida.

And so it must be, if town centers are to flourish. But Kramer was also driven by a desire to create a unique new place—and he has pursued a vision of that place steadfastly for many years.

Kramer and his partner, Matthew Kaskel, spent the early years of Haile Plantation’s development thinking carefully about just what kind of place the village center should be. From the very beginning, they envisioned it as a traditional village center, and visited dozens of small towns and villages to collect ideas, writing out lists of social, community, and civic qualities and activities that the center should foster. But without their confidence in the center’s ability to turn a profit, it would never have been built.

Today there are nearly 100 new town center projects of various types planned or under construction, and older main streets and downtowns are being renovated in an estimated 6,000 communities of all sizes.1 After a break of nearly 50 years, why are so many plans and projects for new, mixed-use town centers, main streets, and urban villages now emerging?2

Until recently, the perception was that there was no money to be made in main street and town center projects. While developers and local redevelopment agencies worked hard to create successful mixed-use projects in downtown areas, fine-grained and pedestrian-friendly mixed-use developments in the suburbs continued to be viewed as inherently risky. Proposals for urban-scale, mixed-used developments in suburban settings were associated with the lunatic fringe, and were met with severe skepticism by financiers, potential tenants, local neighborhood groups, and public officials. Only edge-city locations were acceptable grounds for experimentation, and then only on a scale designed for the automobile, not for pedestrians. Why are main street and town center projects suddenly the focus of attention? What forces have come together to transform these projects from risky trips down memory lane into attractive investments and trend-setting developments? The forces are many, and include changing market demands, shifting public policy, new urban design ideas, and the cultural changes that are occurring as the tastes and attitudes of the Depression-era generation yield to those of the baby boomers, Generation X-ers, and beyond.

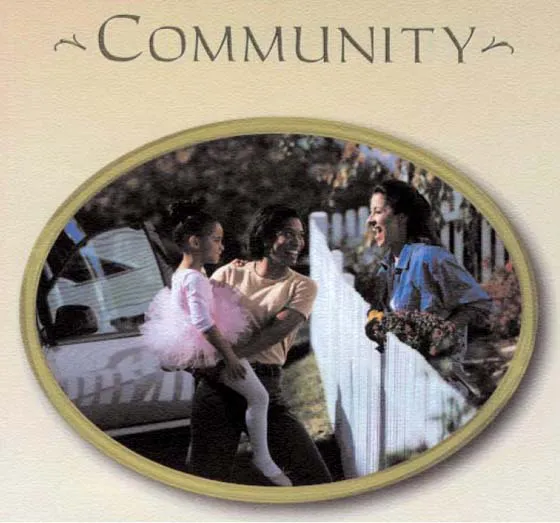

Marketing “community” at Lakelands, the home of Market Square, in Gaithersburg, Maryland. Courtesy Natelli Communities.

The “Quest for Community”

According to Real Estate Development: Principles and Process, “the excitement of identifying an unfulfilled human need and creating a product to fill it at a profit is the stimulus that drives development.”3 Without sufficient demand for main street and town center settings, developers would not be going to such great lengths to build these complex and challenging projects, and municipalities would be extremely reluctant to approve and invest public funds in them. But with virtually no track record, what are the indications that there is a demand for such projects? What human needs are they designed to fulfill?

While surveys indicate that Americans continue to embrace the single-family home, they also reveal an extraordinary discontent with what Reid Ewing refers to as “the rest of the suburban package.” In “Counterpoint: Is Los Angeles—Style Sprawl Desirable?”, Ewing summarizes a wide variety of research supporting this view, including 11 studies indicating that “given the choice between compact centers and commercial strips, consumers favor the centers by a wide margin.”4 Lending further support are the 1995 American LIVES survey, which found that nearly 70 percent of those surveyed were unhappy with suburbs as they currently exist, and the Pew Center’s February 2000 survey, in which “sprawl” was cited as the number one concern across the nation.5 Much of the torrent of media attention focused on sprawl targets the patchwork of strips, centers, and “pods” of separate retail, office, and multifamily developments—an agglomeration that many people consider unattractive, congestion-inducing, and mind-numbingly monotonous.

According to real estate analyst Christopher Leinberger, “the real estate development industry now has 19 standardized product types—a cookie-cutter array of office, industrial, retail, hotel, apartment, residential, and miscellaneous building types.”6 Leinberger notes that the formulas for these product types have been refined over many decades, making them relatively “easy and cheap to finance, build, trade, and manage.” These development products are clearly successful at meeting the needs of businesses and consumers and form the very fabric of our metropolitan regions. However, while the real estate industry has become very good at building these projects, the projects themselves are not very good at building communities.

One alternative touted by smart growth advocates and new urbanists is to reconfigure portions of suburban office, retail, and higher-density residential development on infill sites to create traditional town centers or urban villages. These town centers would be designed as compact, mixed-use, pedestrian-oriented places—of the sort that could provide communities with a focal point and civic identity.

“Third places” as an endangered species: a parking lot “café” in Durham, North Carolina.

Outdoor dining at Mizner Park, in Boca Raton, Florida.

Americans’ genuine dissatisfaction with sprawl and their interest in alternatives appear to be two sides of the same coin. The American LIVES survey, in which a remarkable 86 percent of suburban home-buyers stated a preference for town centers, also found that 29 percent favored the status quo, with “shopping and civic buildings distributed along commercial strips and in malls.”7

These sentiments, often described as a “quest for community,” are apparent in the titles of recent books, such as Philip Langdon’s A Better Place to Live, Terry Pindell’s A Good Place to Live: America’s Last Migration, and James Howard Kunstler’s Home From Nowhere.8 For the authors of these and other books and articles, the elements most commonly identified as missing are what sociologist Ray Oldenburg has referred to as “third places.” Third places are the traditional community gathering places found outside the home (our “first place”) and the workplace (our “second place”) and include cafés, taverns, town squares, and village greens.9 Where development is completely organized around the requirements of automobile travel, third places either become islands in a sea of parking, cut off from nearby neighborhoods—or, in the case of town squares and village greens, they become extinct. Many observers are convinced that these community gathering places are the missing ingredients that people in suburban areas and edge cities are looking for today. As Pindell writes, “Towns and cities whose social life coalesces around such places rather than the country club and the private home meet the first criteria for people looking for a good place to live today.”10

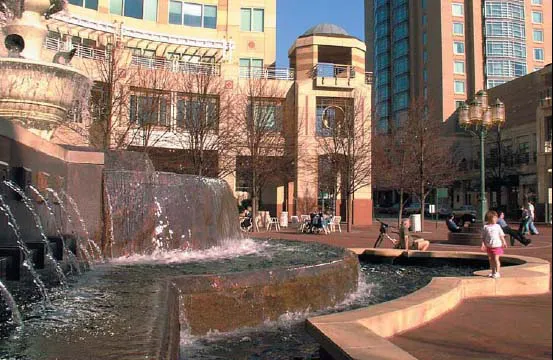

The space between buildings—the public realm—such as at Reston Town Center’s Fountain Square, Reston, Virginia, enables a town center or a main street to act as the “third place” for nearby neighborhoods.

Newly created settings, like Mizner Park’s Plaza Real and Reston Town Center’s Fountain Square and ice-skating pavilion, are proving that these types of community gathering places are not simply nostalgic archetypes advanced by urban-history buffs, but real magnets for residents and visitors. Like colonial New England villages, today’s town center projects typically revolve around a central plaza or park that establishes a public atmosphere and provides an ideal setting for the cafés, taverns, and bistros celebrated by Oldenburg. In fact, it is the space between buildings—the public realm of plazas, greens, squares, and walkable streets—that enables a town center or a main street to act as the third place for nearby neighborhoods and communities.

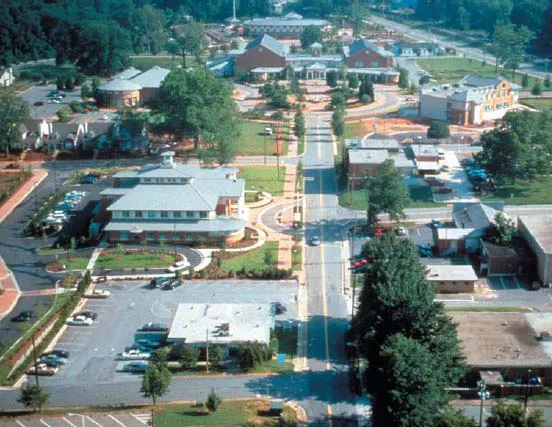

Smyrna Town Center, the emerging town center of Smyrna, Georgia. Courtesy Sizemore Floyd Architects.

Place Identity

Closely related to the quest for community is the growing appreciation of how town centers, main streets, and urban villages can “put communities on the map,” and establish a strong identity for new residential communities and existing towns and suburbs. Maturing edge cities, like Schaumburg, Illinois, and Owings Mills, Maryland—still touted by Joel Garreau, author of Edge Cities, as the wave of the future—are particularly likely to experience an identity crisis as the sum of their parts fails to add up to a community. When asked to explain the reasoning behind Baltimore County’s proposal to create a town center for Owings Mills, the county executive explained, “It will give this community a heart, an identity, and a focal point.”11 Even Tysons Corner, Virginia, the epitome of Garreau’s edge city, is moving forward with a town center project. Commenting on the proposal, Fairfax county supervisor Gerald E. Connolly explained, “The idea is to try to put some personality into Tysons.” As architect Rod Henderer, vice president of RTKL Associates, Inc., added, “There’s a huge amount of office space, but there’s never been a civic heart to Tysons. This is a measure to give that to Tysons. Most cities have a sense of place about them. Tysons does not, and it needs one.”12

For MPCs developed in the 1960s and 1970s, which consisted of hundreds or thousands of acres of low-density suburban neighborhoods, a town center can provide both a literal and symbolic center for the community in a way that a golf course and clubhouse cannot. Early village centers, like those in Columbia, Maryland, and Reston, Virginia, used a combination of innovative and conventional retail forms but fell short of expectations as both commercial and community centers. Reston’s Lake Anne Village, for example, placed housing over retail along a lakefront, an innovative approach that performed poorly, in part, because it offered limited visibility from nearby roads that were not high-traffic to begin with. But whereas Lake...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Place-Making Trend

- Chapter 2 Learning From the past: Town Centers and Main Streets Revisited

- Chapter 3 Timeless Design Principles for Town Centers

- Chapter 4 Emerging Formats for Town Centers, Main Streets, and Urban Villages

- Chapter 5 Launching a New Town Center: Feasibility and Financing

- Chapter 6 Breakthrough Projects Revisited

- Chapter 7 Case Studies

- Chapter 8 A Compendium of Planning and Design Ideas for Town Centers