eBook - ePub

The Power of Ideas

Five People Who Changed the Urban Landscape

- 121 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book profiles five fascinating visionaries who exemplify outstanding leadership, a passion for their work, cutting-edge ideas, and a commitment to quality. All winners of the prestigious J. C. Nichols Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development, they include Joseph Riley, mayor of Charleston, South Carolina; Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan; Gerald Hines; Vincent Scully Jr.; and Richard D. Baron.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Power of Ideas by Terry Lassar,Douglas R. Porter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Artist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

DANIEL PATRICK MOYNIHAN

STATESMAN OF THE

PUBLIC REALM

HE BROUGHT TO HIS TASK LUMINOUS INTELLECT, PERSONAL CONVICTION, DEEP HISTORICAL KNOWLEDGE, THE EYE OF AN ARTIST AND THE PEN OF AN ANGEL, AND, ABOVE ALL, AN INCORRUPTIBLE DEVOTION TO THE COMMON GOOD. JAMES Q. WILSON FORMER SHATTUCK PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT HARVARD UNIVERSITY

DANIEL PATRICK MOYNIHAN always loved trains and was supremely bothered by the peeling paint of the scenic Hell’s Gate Bridge that joins the New York boroughs of Queens and the Bronx. The grand old bridge had not been painted in more than half a century. Amtrak didn’t care, but Moynihan did. The senior senator had enough clout with Amtrak and the U.S. Department of Transportation to get them to agree to paint the bridge in 1992. But first, he set up a color selection committee of esteemed designers and urbanists: architect David Childs, now lead designer of the Freedom Tower at the site of the World Trade Center; abstract painter Bob Wyman; president of the Municipal Art Society (MAS) Kent Barwick; and a husband-and-wife team of color consultants who had recently completed work on new galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After deliberating for several weeks, they finally agreed on a shade of maroon that reminded them of the color of the old Pennsylvania railroad cars. They sent a bucket of the maroon paint to the senator in Washington. “He said the color was absolutely perfect,” notes Barwick.

MOYNIHAN’S ACHIEVEMENTS ARE WORTHY OF THE GREAT PUBLIC BUILDERS, FROM HADRIAN TO GEORGES HAUSSMANN TO ROBERT MOSES, ONLY MOYNIHAN’S ARE HUMANE. ROBERT PECK, FORMER MOYNIHAN CHIEF OF STAFF AND FORMER COMMISSIONER OF PUBLIC BUILDINGS SERVICE OF THE U.S. GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION

Who else in Congress would have cared enough to get the bridge painted? Who else would have bothered to assemble a committee of design cognoscenti to select just the right hue?

Cities, architecture, and grand civic spaces were constant themes throughout Moynihan’s career. The public square he loved best was the one he spent half a lifetime reviving.

FIXING UP THE NATION’S MAIN STREET

On the drive back from his inaugural in 1961, President Kennedy was dismayed at the shabby state of the nation’s Avenue of the Presidents. Designed as the great ceremonial axis linking the White House and the Capitol—a physica symbol of the separate, but unified branches of the American government—Pennsylvania Avenue was lined on one side with monumental buff-colored limestone buildings in the neo-classic style. On the other side were mostly decrepit brick buildings with pawnshops, liquor stores, and peep stalls. Kennedy asked Arthur J. Goldberg, his secretary of labor, to do something about cleaning up the avenue. Goldberg formed a committee to look into construction of new federal office space and recommendations for reviving Pennsylvania Avenue. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, special assistant to Goldberg, was put in charge of writing the recommendations. So goes the legend.

DANIEL PATRICK MOYNIHAN IS ONE OF THE FEW PEOPLE IN NATIONAL PUBLIC LIFE TODAY WHO REALLY RESPONDS TO ARCHITECTURE, WHO … KNOWS THAT GREAT CITIES ARE MADE UP NOT ONLY OF INDIVIDUAL GREAT BUILDINGS, BUT OF WONDERFUL PLACES—STREETS, PUBLIC SQUARES, TRAIN STATIONS—IN WHICH WE LIVE OUR PUBLIC LIFE TOGETHER. HE HAS ALWAYS UNDERSTOOD THAT A BETTER PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT CAN MAKE LIFE MORE SATISFYING, AND HAS DONE AN INCREDIBLE JOB OF MAKING THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT A FORCE BEHIND GOOD ARCHITECTURE AND BETTER CITIES. PAUL GOLDBERGER, ARCHITECTURE CRITIC

Pennsylvania Avenue during John F. Kennedy’s inaugural parade in January 1961.

When Daniel Patrick Moynihan joined President Kennedy’s new administration in 1961 as specia assistant to Secretary of Labor Goldberg, he had already earned a reputation as a politically inclined intellectual and urban expert. He had worked almost four years as an assistant to Governor Averell Harriman and had taught at Syracuse University. “Moynihan’s first act of note on the national stage,” says Robert Peck, who served as chief of staff to the senator, “was as a city planner.” His ambitious proposal for reviving Pennsylvania Avenue was hitched at the end of the banal-sounding document, “Report to the President by the Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space,” issued in 1962. The strategy of burying the proposal in an appendix to a turgid report on government office space, along with a set of “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture,” has led some people, like Peck, to think that the whole thing, including the Kennedy legend, was a Moynihan invention. Peck believes that Moynihan was so loyal to the memory of Kennedy that he credited the president with the idea of fixing up Pennsylvania Avenue.i

NO OFFICIAL STYLE

However it happened, Moynihan turned what many would have treated as a routine assignment into an opportunity to establish federal architectural policy. “The belief that good design is optional, or in some way separate from the question of the provision of office space itself, does not bear scrutiny,” he wrote with his trademark vigor. His first directive was to be contemporary: “avoid an official style.” Government buildings should embody the “finest contemporary architectural thought.” At that time, the federal government, according to Moynihan, had built scarcely a contemporary building in Washington in two generations. He knew, however, that recognizing the contemporary architecture of the time did not guarantee excellence. “There are great moments in architecture, there are lesser moments. But we wouldn’t miss any.”ii

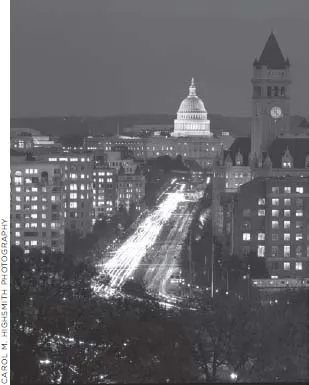

Pennsylvania Avenue today—after Senator Moynihan devoted half his life to its revival.

Moynihan’s proposal for reviving Pennsylvania Avenue traced the history of the architecture of the nation’s capital, starting with the original plans of Major Charles Pierre L’Enfant, in which the grand axis of Pennsylvania Avenue—connecting the separate branches of government—was to be the main thoroughfare of the city of Washington. Instead, Moynihan noted, “It remains a vast, unformed, cluttered expanse at the heart of the Nation’s Capital,” and the main court of the Federal Triangle (the Depression had stopped construction to complete the Triangle) was left to become a parking lot of “unsurpassed ugliness.”iii

In the Ad Hoc Committee report, Moynihan worried that the Capitol itself was “cut off from the most developed part of the city by a blighted area that is unsightly by day and empty by night.” Large sections on the north side of the street were decayed beyond repair; many buildings would have to be replaced. Moynihan saw this as a great opportunity that might “not come again for a half century or more.”

So began Moynihan’s stewardship of rebuilding Pennsylvania Avenue, which would take nearly the rest of his life. One would assume that a proposal for redeveloping Pennsylvania Avenue, which was tacked onto a report to alleviate the shortage of federal office space, would endorse, not criticize, extending the Federal Triangle’s phalanx of efficient office buildings along the north edge of the avenue. But Moynihan’s recommendations reached far beyond a simple request for new office space. His ambitious proposal called for creating a lively mix of shops, offices, and housing, along with theaters and other arts facilities and great civic spaces that would be developed jointly by public and private interests.

The government had not built significant office space in Washington since the Federal Triangle buildings, which ended with the 1929 crash. Like most other federal agencies in the 1960s, the labor department was scattered in numerous buildings throughout the city. It was anticipated that the underdeveloped parts of the avenue would be turned into office space for federal workers. But Moynihan was concerned about isolating the Capitol, which he knew would happen if the north side were to be lined, like the south side of the avenue, with only office buildings that emptied out after 6:00 p.m. He envisioned more diverse mixed-use development, including housing, for the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue. This mixed-use concept, which Moynihan believed would enliven the city, was exceptionally urban for the time.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR FEDERAL ARCHITECTURE

In the course of its consideration of the general subject of Federal office space, the committee has given some thought to the need for a set of principles which will guide the Government in the choice of design for Federal buildings. The committee takes it to be a matter of general understanding that the economy and suitability of Federal office space derive directly from the architectural design. The belief that good design is optional or in some way separate from the question of the provision of office space itself does not bear scrutiny, and in fact invites the least efficient use of public money.

The design of Federal office buildings, particularly those to be located in the nation’s capital, must meet a twofold requirement. First, it must provide efficient and economical facilities for the use of Government agencies. Second, it must provide visual testimony to the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American Government.

It should be our object to meet the test of Pericles’s evocation to the Athenians, which the President commended to the Massachusetts legislature in his address on January 9, 1961: “We do not imitate—for we are a model to others.”

The committee is also of the opinion that the Federal Government, no less than other public and private organizations concerned with the construction of new buildings, should take advantage of the increasingly fruitful collaboration between architecture and the fine arts.

With these objects in view, the committee recommends a three-point architectural policy for the Federal Government.

1. The policy shall be to provide requisite and adequate facilities in an architectural style and form which is distinguished and which will reflect the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American National Government. Major emphasis should be placed on the choice of designs that embody the finest contemporary American architectural thought. Specific attention should be paid to the possibilities of incorporating into such designs qualities which reflect the regional architectural traditions of that part with emphasis on the work of living American artists. Designs shall adhere to sound construction practice and utilize materials, methods, and equipment of proven dependability. Buildings shall be economical to build, operate, and maintain, and should be accessible to the handicapped.

2. The development of an official style must be avoided. Design must flow from the architectural profession to the Government and not vice versa. The Government should be willing to pay some additional cost to avoid excessive uniformity in design of Federal buildings. Competitions for the design of Federal buildings may be held where appropriate. The advice of distinguished architects ought to, as a rule, be sought prior to the award of important design contracts.

3. The choice and development of the building site should be considered the first step of the design process. This choice should be made in cooperation with local agencies. Special attention should be paid to the general ensemble of streets and public places of which Federal buildings will form a part. Where possible, buildings should be located so as to permit a generous development of landscape.v

Hardly anyone knows, says Peck, that Moynihan also wanted to deploy a concert hall, theater, and opera house at points along the avenue to animate it. Apparently, there had long been talk of creating a national cultural center in Washington. President Kennedy asked Moynihan and his colleagues to present this idea, along with plans for redeveloping the avenue, to congressional leaders on his return from Dallas. But tragedy interfered.

An informal President’s Advisory Council on Pennsylvania Avenue was set up to carry out the proposal, cochaired by Moynihan and Nathaniel Owings, from the San ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Titlepage

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgment

- Foreword Paul Goldberger

- Introduction

- Joseph P. Riley, Jr.: Caring for Cities

- Daniel Patrick Moynihan: Statesman of the Public Realm

- Gerald D. Hines: Developer Extraordinaire

- Vincent Scully: Visionary Teacher, Writer, Advocate

- Richard D. Baron: Doing Well at Doing Good

- Backcover