![]()

Chapter 1

The Development Process

Real estate development requires diverse disciplines and activities to convert an idea into a completed project. The work up to completion must be paid for with invested time and capital supported by the property’s finished development value, which results from either income or sales. Construction costs are the largest component of project costs, followed by land, architecture and engineering, legal, financial, environmental, management, marketing, and communications. Each discipline involves a different array of staff, contractors, and consultants who have different skills and roles. All these disciplines cannot function coherently without the skill of the real estate developer, who coordinates the different activities to create value. One of the most important skills that a developer brings to this process is the ability to obtain and manage appropriate equity and debt financing to fund these activities in a timely and cost-effective manner.

This chapter starts with a brief overview of real estate as a sector of the economy, its dependence on capital markets, and its dynamic nature. The chapter then describes the development process, its tasks, the overarching questions that a developer must address, the skills necessary to be a successful developer, and the role of finance in the development process. It concludes with an overview of the main sectors of real estate and their customer risk and absorption profiles.

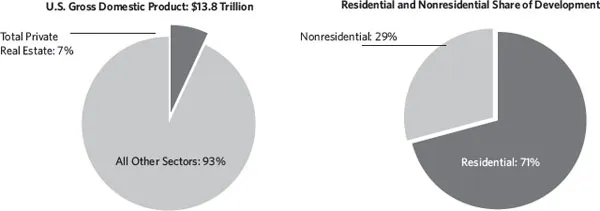

Real Estate Overview

In 2007, private construction activity for commercial and residential real estate development in the United States totaled approximately $700 billion, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. With the addition of a reasonable estimate of 40 percent of this figure to account for land, design, financing, and other development costs, the real estate development sector contributed about 7 percent to gross domestic product (GDP) (Figure 1–1). Of this activity, about 71 percent was residential; the other 29 percent was nonresidential, including retail, office, industrial, lodging, education, and health care.

In addition to its contribution to ongoing economic activity, commercial real estate is an important investment category for major investors in their allocation of portfolio assets. Commercial real estate has a relatively low total capitalization compared with U.S. stocks, according to the CME Group (figure 1–2). When combined with residential real estate, however, the value of U.S. real estate exceeds that of U.S. stocks and is approximately equal to that of the U.S. bond market.

FIGURE 1–1

Real Estate Development: Share of GDP and Distribution Between Major Sectors, 2007

Note: Based on 40% adjustment for land value and return on capital.

FIGURE 1–2

Private Real Estate Value Compared with U.S. Stock Market Valuation, 2006

Source: CME Group.

Commercial real estate has grown in importance as an investment asset class over the past several decades, in part owing to new laws and new investment vehicles. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 substantially reduced tax rates for all taxpayers and eliminated accelerated depreciation for real estate, thus making real estate less of a tax shelter and more of an income-producing asset. (This change is discussed further in chapters 5 and 10.) The Act also broadened the investment scope of real estate investment trusts (REITs), making them development and management entities instead of merely lenders. These publicly traded investment vehicles made real estate investments accessible to many more investors. Then, in the early 1990s, following a disastrous real estate recession, the financial markets developed commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), which sold securities backed by pools of real estate loans—resulting in substantially enhanced access to debt for the real estate sector. (Chapter 5 provides more detail on the effects of these two changes.) Private equity funds, backed by institutional money and high-net worth investors, also entered the landscape in the 1990s, often focusing on opportunistic investments. These changes together substantially transformed the real estate industry and increased the capital available for real estate investment, ultimately resulting in a far more sophisticated investment landscape with a broader set of participants and vehicles.

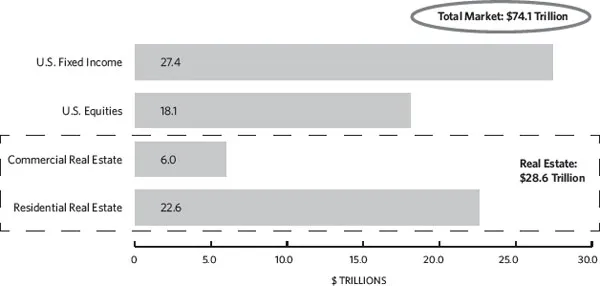

FIGURE 1–3

Performance of Real Estate, Stocks, and Bonds

Notes: Data intervals are as of September 1 each year. AGG = Barclay’s Capital Aggregate bond Index. S&P = Standard & Poor’s. C-S 20 = Case-Shiller 20-city housing price Index. MIT CRE = Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Real Estate.

As these changes propagated through the industry, real estate competed more effectively with other asset classes for capital and attracted the interest of more investors. In the early 2000s, real estate performed better than equities and fixed-income securities, largely because it was perceived as low risk; that is, as “always going up.” Figure 1–3 compares the performance of bonds, stocks, commercial real estate, and residential real estate for the period from 2004 to 2010. Early in this period, real estate—both commercial and residential—outperformed both the equity and the fixed-income sectors; but in 2008, stocks and real estate collapsed and capital flowed out of real estate and stocks and into the safe haven of bonds. Then, while stocks recovered, real estate lagged as investors realized how much its performance correlates with jobs and capital availability.

More recently, the Great Recession of 2007 to 2008 highlighted not only the cyclical nature of the real estate industry but also its dynamic nature. Valuation losses in many markets and for many sectors placed property values below replacement costs, thus deferring development in these markets and sectors for some time, until valuations recovered to at least replacement levels. Investors redirected their energies toward new opportunities as distressed properties became available at much lower prices.

Inherently, real estate is a dynamic industry that adjusts to changing market and capital opportunities. The history of real estate development for the last two generations underscores this dynamic characteristic. Starting in the 1950s, with the baby boom and the mobility created by the automobile, the development industry responded with innovative housing production and auto-oriented suburban retail. Although some viewed this response with disdain (think of Malvina Reynolds’ lyrics—”little boxes made of ticky-tacky”—or Joni Mitchell’s—”They paved paradise and put up a parking lot”), it provided needed housing and created communities that reflected the sense of freedom of a nation with wheels. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, as urban centers lost commerce and residents, the industry corrected many of its commodity-driven practices and responded to demand for new, higher-quality forms of retailing such as shopping malls and office parks. Gradually, in the 1980s and 1990s, suburbs became fringe cities and the concepts of business parks, lifestyle centers, and place making evolved. Beginning in the late 1990s, as people yearned for identity, the industry advanced the concept of smart growth and town centers, and mixed-use development evolved. Going forward in the 2010s, the development industry will continue to respond to evolving demands with more sustainable development, more infill, more revitalization, and more mixed-use products.

The dynamism in the industry relies on the capacities of the professional developer to recognize and harness market demand, to enable the creativity and practicality of architects, contractors, marketers, and financiers to produce value from ideas. Starting with an idea and a piece of land and, perhaps, a major tenant, the developer puts money and time at risk to design a project, obtain community support, buy land, and—if financing sources can see that it will work—to construct and close out the project. The developer is the conductor of a complex, multidisciplinary process that depends on exogenous forces, especially market demand and capital availability. No other industry creates a product that involves the collaborative effort of so many disciplines in such a publicly accountable process. Real estate development is unique. In this chapter we begin learning how to do it effectively.

The Development Process and Risk

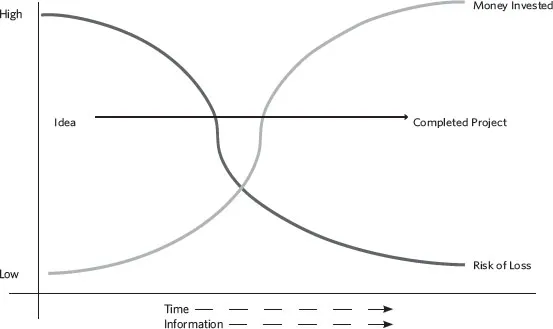

Development involves putting increasing amounts of investment capital at risk over time. As more capital is invested, the risk to that investment should be reduced by the growing certainty that the project will be successful and provide returns to investors.

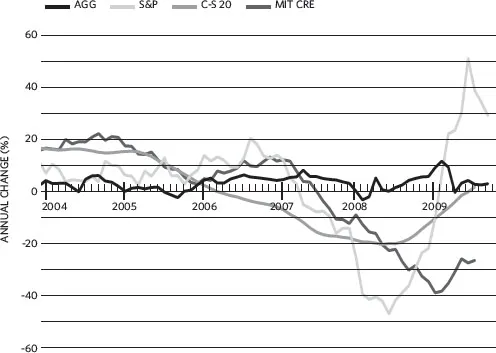

Figure 1–4 diagrams the risk and cost profile of a typical real estate development project. Costs increase with time, but the risk profile is the inverse of the cost profile. Risks from unknown and uncontrollable factors are high in the early stage, when uncertainty is high because of scarce information. Risk lessens as the project proceeds through design to entitlement and financing as more information is developed, uncertainties are resolved, and—most important—risk is controlled through competent management strategies.

At the initiation of a new development project, the developer evaluates two dimensions of economic viability. First, can the project pay a return on investment if it is actually built? Second, and equally important, does the developer have sufficient capital to fund the early project costs to bring the project to a stage where it can be financed and built? This second dimension highlights the risks that the developer takes to get a project to the point at which it can demonstrate viability and thereby attract capital from outside investors and lenders.

The early costs of a development project are relatively low; they involve investigatory work, market analyses, preliminary design, navigating the approval process, cost estimating, and site analysis—costs categorized as “soft costs” and typically paid from the developer’s own capital, at least until project viability has been demonstrated to a financing source and outside funding becomes available. With time, these costs can accumulate to be quite significant—reaching into millions of dollars for larger projects and hundreds of thousands for smaller projects. The risks and funding of these predevelopment costs can constitute a major challenge to the economic viability of a real estate development project, especially in areas where the entitlement process is long, costly, and uncertain.

The first significant cost that a project incurs is, typically, acquiring either the land or an option to buy the land. Knowing how to evaluate what a project can afford to pay is crucial. Land value for a project must be evaluated on the basis of the “residual” of the project’s value less all development costs (including an adequate return), not on the basis of comparables or appraisals. (Chapter 3 addresses this issue in detail.)

FIGURE 1–4

Risk-Cost Profile of Development

Costs grow as the project becomes more complete, as entitlement applications are filed, as community groups are engaged in the entitlement process, and as equity and debt financing sources are pursued. By the start of construction, the risks to project success are largely confined to managing construction, reacting to unforeseen market downturns, and executing the marketing, leasing, and management plan. Of these, only market conditions are beyond the control of the development team.

Any project faces the very real risk that the market could collapse during construction, resulting in reduced leasing or sales, and project failure. During construction, there is the risk that costs and construction time could exceed projections, resulting in funding shortfalls or a higher carrying cost for capital. The developer’s challenge at the beginning of a project is to identify the issues that represent future risk and to conceive of and implement competent management strategies to mitigate them. Market collapse and constructio...