- 454 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Retail Development

About this book

This comprehensive book is a practical how-to guide to developing hot retail projects such as lifestyle centers, mixed-use centers, and rehabs of failed malls. Project sizes range from small, ethnic-oriented community centers to major multilevel malls.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

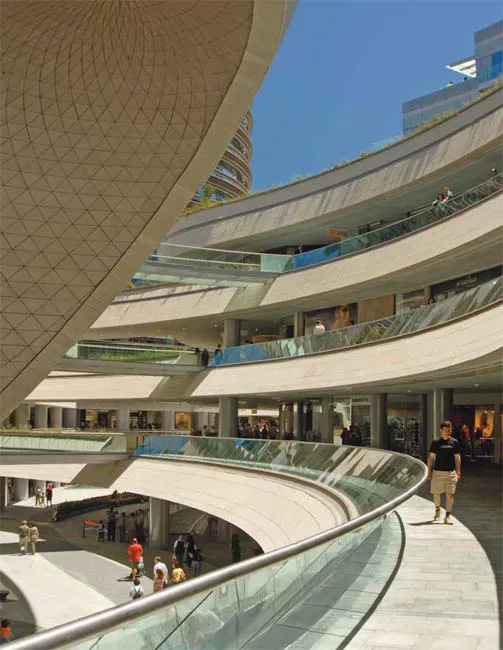

Kanyon, lined with four levels of retail and entertainment space in the financial heart of Istanbul, Turkey, is designed to provide year-round comfort in an open-air setting. A canopy over the storefronts shields shoppers from direct sunlight during the summer, and radiant-heat panels in the ceilings create a microclimate of roughly 60 degrees Fahrenheit (15.5 degrees Celsius) during the winter when the outdoor temperature is at freezing.

1. Introduction

The shopping center industry has matured and is facing new challenges and opportunities. The great spurt of shopping center construction over the past almost 60 years that has led to an estimated 50,000 centers with more than 10,000 square feet (930 square meters) of gross leasable area in the United States alone has now slowed as suburban markets have become saturated—but it has by no means come to a halt. Competition is intense as obsolete centers are eclipsed by newer concepts, designs, retail formats, combinations of tenants, and site plans. Along with new construction, major forces in the industry today are redevelopment, repositioning, retenanting, and reconfiguration as the immense inventory of retail properties ages. Although the competition has created unprecedented risks for many existing properties that have not kept pace with emerging trends, it has also created enormous opportunities that sophisticated shopping center owners and developers are making the most of at the expense of their less nimble competitors.

The variety of shopping center formats, whether new development or transformation, is expanding, and hybrids are becoming increasingly common: streetfront, infill projects that seamlessly connect to an existing urban setting; town centers on greenfields that will be the core for future development; mixed-use shopping districts that replace a single monolithic shopping center or are the core of a planned community. New formats go farther than previous generations of shopping centers, providing, in addition to centers for shopping, nonretail activities, entertainment, and public open spaces. These new mixed-use elements are incorporated vertically or horizontally and to varying degrees into large and small centers.

These changes in the feel and shape of shopping centers are a response to a combination of trends: changing urban design ideas; increasing land prices in developed areas, consumer interest in urban environments—even in suburban and exurban areas—and cities’ interest in creating strong and sustainable communities. Development projects driven foremost by retail may now also include housing, hotels, office space, and public uses to maximize returns from the site and create the desired ambience. Single-use retail development may evoke additional activity through attention to public space, entertainment, and food service. The notion of community has evolved so that today the connection to community is literal (with newly created streets internal to a development site linked to existing streets and storefronts directly on existing streets), interactive (gathering places specifically designed to encourage meeting, eating, and greeting), and aspirational (bringing stores together that reflect how customers view themselves, their community, and their environment).

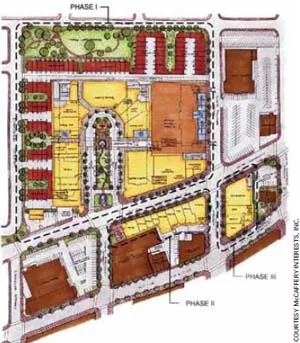

The Market Common, Clarendon, in Arlington, Virginia, is one of the early examples of a successful open-air retail center in a mixed-use, urban infill setting. McCaffery Interests, the developer, drew inspiration from Mizner Park in Boca Raton, Florida. The first and largest phase of Market Common is built around a new U-shaped road and courtyard. The approximately 250,000 square feet (23,235 square meters) of retail in this phase includes two-story anchor tenants in the end-cap locations and at the far end of the looped road. Apartments and offices rise above the retail. Before development, the site was a 600-space surface parking lot. Parking is now primarily subterranean.

These changes after years of mostly stand-apart shopping center development have led to the perception that many of these new formats are not necessarily shopping centers but something else—districts, downtowns, or just the center of a community. They do, in fact, function as shopping centers, but to reflect the changes in formats and commonly used descriptive terms, which are in turn based on trends that are growing stronger and broader and have produced numerous benefits for shoppers and their communities, the title of this book has been changed from Shopping Center Development Handbook (the previous edition in 1999) to Retail Development.

Notwithstanding new developments in shopping centers, the fundamentals of development or redevelopment remain the same—the need to determine feasibility; finance the project; plan and design the site, buildings, and parking; develop and implement a tenanting strategy; and manage and operate the project when it is open. These fundamentals are covered in detail in subsequent chapters and apply to both traditional shopping centers, new formats, and all the variations and hybrids in between.

What Is a “Shopping Center”?

Distinct from other forms of commercial retail development, the shopping center is a specialized, commercial land use and building type. Today, shopping centers are found throughout the world but until the late 1970s thrived primarily in U.S. suburbs, occurring only rarely in downtowns or rural areas. Over the years, shopping centers have been transformed from a suburban concept to one with much broader and varied applications and locations. The Urban Land Institute standardized the definition of “shopping center” and related terms. In 1947, ULI defined a shopping center as:

… a group of architecturally unified commercial establishments built on a site that is planned, developed, owned, and managed as an operating unit related by its location, size, and type of shops to the trade area that it serves. The unit provides on-site parking in definite relationship to the types and total size of the stores.1

Zona Rosa, with its town center format, creates a destination in the northern Kansas City, Missouri, suburbs. Architectural dissonance in the retail center makes it seem as though the project evolved over the decades and reinforces a sense of place for the community. The lack of signs with Zona Rosa’s name at the site or nearby undergirds the notion that Zona Rosa is a place, not a shopping center.

Zona Rosa during construction.

In the decades that followed, ULI refined this definition so that a shopping center must also have a minimum of three commercial establishments, and, in the case of urban shopping centers, its on-site parking needs may be related not only to the types and sizes of the stores but also to the availability of off-site parking and alternate means of access.

Although the scope of this revised definition still appears broad, it actually is rather restrictive and excludes much retail development. Individual retail stores, even when grouped side by side along streets and highways or owned by a single owner, are excluded if they are not centrally managed. Thus, any number of commercial strips or downtown shopping clusters do not qualify as shopping centers, although they may constitute significant shopping districts. On the other hand, an intergrated shopping center can form the nucleus of a shopping district in an existing or emerging commercially zoned area, or it may represent the first project around which other commercial land uses eventually are developed. Today, what may appear to be individually managed shops may actually be centrally managed, as in the case of a well-integrated infill project.

The following elements more fully describe the well-planned shopping center and set it apart from other commercial land uses:

- Coordinated architectural treatments, concepts, or themes for the building or buildings, providing space for tenants that are selected and managed as a unit for the benefit of all tenants. A shopping center is not a miscellaneous or unplanned assemblage of separate or common-wall structures. Moreover, a coordinated architectural approach does not imply that all buildings must appear the same. On the contrary, architectural diversity in style and height among buildings and/or tenants is desirable for tenant identity, project authenticity, and overall enjoyment of the shopping experience. It does mean that overall planning and control are important.

- A unified site suited to the type of center called for by the market. The site may permit expansion of buildings and addition of new buildings, uses, or parking structures if the trade area and other growth factors are likely to demand them.

- An easily accessible location in the trade area with efficient entrances and exits for vehicular traffic as well as convenient and pleasurable access for transit passengers, where appropriate, and pedestrians from surrounding development.

The Market Common, Clarendon, in Arlington, Virginia, took advantage of the underdeveloped site’s proximity to a mass transit station and the need for greater density. This pedestrian-oriented development revitalized the Clarendon neighborhood with approximately 303,000 square feet (28,000 square meters) of retail, 87 residential townhouses, and 300 apartments.

In addition to two underground parking garages, Clayton Lane in Denver, Colorado, includes a mixed-use parking structure: a five-level, 454-space parking garage with 16,000 square feet (1,490 square meters) of street retail, 5,300 square feet (490 square meters) of office space, and a 21,000-square-foot (1,950-square-foot) Sears Auto Center in the basement of the structure.

Kierland Commons—a mixed-use retail center in a master-planned community in Scottsdale, Arizona— incorporated extensive landscaping and large sidewalk canopies to create a comfortable and aesthetically pleasing atmosphere.

- Sufficient on-site parking to meet demand generated by the retail uses. Parking should be arranged to enhance pedestrian traffic flow to the maximum advantage for retail shopping and to provide acceptable walking distances from parked cars to center entrances and to all individual stores. Where alternative modes of transit are available, the definition of “sufficient” may change.

- Service facilities (screened from customers) for the delivery of merchandise.

- Site improvements such as landscaping, lighting, and signage that create a desirable, attractive, and safe shopping environment.

- A tenant mix and grouping that provide synergistic merchandising among stores and the widest possible range and depth of merchandise appropriate for the trade area and type of center.

- Comfortable surroundings for shopping and related activities that create a strong sense of identity and place.

Although some shopping centers may not exhibit all these characteristics, the most successful shopping centers project a strong overall image and a clearly identifiable orientation for customers and tenants alike. Unified ownership and management and joint promotion by tenants and owners make it possible.

Each element in a shopping center should be adapted to fit the circumstances peculiar to the site, neighborhood, development concept, and market. Innovations and new interpretations of the basic features must always be considered in planning, developing, operating, and remaking a successful shopping center. To succeed, each center must be not only profitable but also an asset to the community where it is located.

Shopping Center Terms

Several terms commonly used in the shopping center development and management industry are used in this book:

- Gross leasable area (GLA) is the total floor area designed for a tenant’s occupancy and exclusive use, including basements, mezzanines, or upper floors, expressed in square feet (or square meters) and measured from the centerline of joint partitions and from outside wall faces. It is the space, including sales areas and integral stock areas, for which tenants pay rent.2 The difference between gross leasable area and gross building area (GBA) is that enclosed common areas and spaces occupied by centerwide support services and management offices are not included in GLA because they are not leased to individual tenants. Specifically, GBA includes public or common areas such as public toilets, corridors, stairwells, elevators, machine and equipment rooms, lobbies, enclosed mall areas, and other areas integral to the building’s function. The enclosed common area may range from less than 1 percent in completely open centers to 10 to 15 percent in centers developed as enclosed malls. Because the percentage of common area varies with the design of the center, the measurement of GLA was developed.

- The parking index also uses GLA to determine the appropriate number of parking spaces for a shopping center, because it affords a comparison between the shopping area and the parking demand from shoppers. In defining the relationship between the demand for parking and the building area of a center, the shopping center industry developed a uniform standard by which to measure parking needs. The standard, known as the “parking index,” is the number of parking spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) of GLA. (See Chapter 4 for a detailed discussion of parking needs.)

- Trade area is that geographic area containing people who are likely to purchase a given class of goods or services from a particular shopping center or retail district. The size of the trade area varies based on the shopping center type and size, tenant categories, proximity of competitive cent...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Project Feasibility

- 3 Financing the Retail Project

- 4 Planning and Design

- 5 Expansion and Rehabilitation of Existing Centers

- 6 Tenants

- 7 Operations, Management, and the Lease

- 8 Management and Promotion of a Successful Center

- 9 Case Studies

- 10 Future Trends

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Retail Development by Anita Kramer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.