- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Children are citizens with autonomy and rights identified by international agencies and United Nations conventions, but these rights are not readily enforceable. Some of the worst levels of child poverty and poor health in the OECD, as well as exceptionally high child suicide rates, exist in Aotearoa New Zealand today. More than a quarter of children are experiencing a childhood of hardship and deprivation in a context of high levels of inequality. Maori children face particular challenges. In a country that characterizes itself as "a good place to bring up children," this is of major concern. The essays in this book are by leading researchers from several disciplines and focus on all of our children and young people, exploring such topics as the environment (economic, social and natural), social justice, children's voices and rights, the identity issues they experience and the impact of rapid societal change. What children themselves have to say is insightful and often deeply moving.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Childhoods by Nancy Higgins,Claire Freeman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Children's Studies in Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

INTRODUCTION

Children in Aotearoa New Zealand – an overview

Claire Freeman & Nancy Higgins

A book on childhood

Currently around a quarter of New Zealanders are experiencing childhood, and one-third of all households include children, yet we know little about how childhood is experienced by children. We know some key statistics: the number of children as a proportion of the population decreased from one in three in 1971 to one in four in 2001; over half of children, at the time of the census, had lived overseas or elsewhere in Aotearoa New Zealand; and only 5% did not have at-home access to telecommunications (Statistics New Zealand, 2002). Children in Aotearoa New Zealand are living in a changing world and planet; they are becoming a smaller proportion of our society; they reflect the increasingly diverse nature of Aotearoa New Zealand’s population; and they are more physically mobile in regards to where they live. They are more connected to the global network than their parents were, and some children are becoming increasingly involved in decisions about their own lives. Children growing up in Aotearoa New Zealand today are experiencing a very different world and a very different childhood from that experienced by previous generations.

Is it a better or worse childhood, or both? Children today have access to a wide choice of excellent well-resourced schools. In rural areas, however, many schools, which are so important for small communities, have closed or are threatened with closure. Many children have increasing access to a vast range of activities, from swimming, kapa haka, BMX riding, surfing, chess and robotics clubs to that ever-present rugby club, but they are also under pressure to succeed academically, culturally and socially in ways that leave some children with little time for childhood.

The environments that Aotearoa New Zealand children live in and visit can be stunning. There are long golden beaches, swimming lakes, mountains and forests; but rivers here are polluted, and children are the most likely population sector to live in overcrowded homes and experience respiratory disease associated with cold, uninsulated housing. Aotearoa New Zealand also has one of the fastest-growing income gaps between the rich and the poor. In 1986 an estimated 11% of children lived in poverty; by 2011, that figure had risen to 25%, or about 270,000 children (Child Poverty Action Group, 2012).

Socially, Aotearoa New Zealand is diverse. It is a bicultural nation in which Māori (the indigenous people) and other New Zealanders experience two cultures, Māori and the European (Pākehā) culture that predominates. There seem to be ‘two worlds’ in Aotearoa New Zealand as well, in that Māori are more likely to experience poverty, violence, and difficulty at school. Within the main Pākehā world, there are also a multitude of New Zealanders of different cultures and ethnicities. Children in Aotearoa New Zealand live in a variety of whānau or family structures. There is no universal Aotearoa New Zealand childhood, but a multiplicity of childhoods that reflect the many ways that the country provides or fails to provide for its children. In this book we explore, and contemplate, the nature of childhood in Aotearoa New Zealand today.

Updating childhood

Our book, we hope, will fill a gap in the literature about childhood in Aotearoa New Zealand, and also provide an enjoyable and informative read. Few books have addressed the overarching nature of Aotearoa New Zealand childhoods. By contrast, there is a wealth of stories written for children,1 as well as a good number of academic books about specific aspects of Aotearoa New Zealand childhood, such as child development (Smith, 2005), inclusive and ‘special’ education (Carrington & MacArthur, 2012; Frazer, Motzen & Ryba, 2005), early childhood and schooling (Duncan, 2012; May, 2011), disability and whānau (Ballard, 1998), children and young people’s rights (Smith, 2000), transitions from school (Nairn, Higgins & Sligo, 2012), play (Sutton Smith, 1981), and most recently, children and democracy (Hayward, 2012). The last study to tackle Aotearoa New Zealand childhood as a whole was Ritchie and Ritchie’s 1978 book Growing up in New Zealand, and as we have identified, much has changed since the children of 1978 became the parents of today.

This book aims to better understand what it means to be a child in Aotearoa New Zealand today. It presents current issues and research about diverse childhoods and ‘growing up’ in Aotearoa New Zealand, focusing on issues such as social justice, children’s voices and rights, identity, societal change and the experience of different childhoods in Aotearoa New Zealand. The first part sets the framework for this book and the context for the study of childhood in Aotearoa New Zealand, looking at Childhood Studies, vulnerability, children’s environments, and considerations around researching with children. In Chapter 2, Anne Smith further discusses the chapters in this book in relation to Childhood Studies theory. Part Two explores diversity in childhood and key issues affecting Aotearoa New Zealand’s children in the past and in the present, including school, play, the law, work and the media as well as the context for different childhood experiences, such as being Māori and disabled, being adopted or fostered, and experiencing other cultures. The final part of the book presents children’s and young people’s voices in diverse settings and with reference to a range of issues, including early childhood, parents in prison, ideas of success, gay–straight alliances in secondary schools, and Māori youth’s transitions to work and adulthood.

The book was initiated by the University of Otago’s Children and Young People as Social Actors Research Cluster. The researchers in this Cluster come from a diverse range of academic disciplines, such as education, Māori studies, health, law, social policy, planning, disability, geography, social work and anthropology. However, despite this wealth of expertise, this is not a book written by the Cluster alone: it also includes contributions from researchers from elsewhere in Aotearoa New Zealand whose work was too important to leave out.

We intend that families, students, policymakers, researchers and academics will use this book as a general resource when exploring what it means to be a child in Aotearoa New Zealand. It will be of interest to social work, sociology, education, and youth work practitioners and students, as well as to a range of childhood-related professions and general readership. This book will inform our community about the diverse nature of childhoods in Aotearoa New Zealand and the issues that need to be addressed so that children can positively participate and be included in a society that takes account of all children’s needs, voices and perspectives.

To set the scene, we now look at the physical, social and economic character of Aotearoa New Zealand, its way of life and the state of children in general. However, Aotearoa New Zealand in the twenty-first century is a connected place, part of a wider global context whose influence on children’s lives we ignore at our peril. It is no longer only Aotearoa New Zealand’s young people, by way of that stalwart institution called the great ‘OE’ (overseas experience), who are connecting internationally, but all of its children and youth.

Aotearoa New Zealand: A good place to grow up?

Aotearoa New Zealand is a small country, with a population of four and a half million people (Statistics NZ, 2011), half a million of whom are Māori. It has a stable population in terms of growth. The population is unevenly distributed, with three-quarters living in the North Island and one-third concentrated in Auckland; around 87% of Māori live in the North Island, though only 24% in Auckland. Significant are the number of New Zealanders living abroad, estimated at around 600,000 (477,000 in Australia). Many of these are young New Zealanders, who after completing high school or tertiary education, go abroad for their OE, a common ‘rite of passage’ for the previous generation as well. While most young New Zealanders do return, not all do, and some return later bringing with them children and partners. A common rationale for returning is the desire to enable their children to have an Aotearoa New Zealand childhood, which brings us to the primary question addressed in this book: is Aotearoa New Zealand a good place to grow up?

According to the United Nations Human Development Report 2013, Aotearoa New Zealand was among the countries in the ‘very high human development’ category, ranking sixth (United Nations, 2013). In the 13th State of the World’s Mothers report (Save the Children, 2012), which ranks the best countries in which to be a mother, Aotearoa New Zealand came fourth behind Norway, Iceland and Sweden. In contrast, the report Measuring Child Poverty ranked New Zealand twentieth out of 35 OECD countries in regards to the percentage of children living in relative poverty (OECD, 2009). Aotearoa New Zealand was in the bottom half for most measures in this report, except literacy. Our suicide rate was the worst, more than twice the OECD average, and our teenage birth rate was also high, surpassed only by Mexico, the United States, Turkey and Britain. These findings accord with the situation identified in The children’s social health monitor 2011 update, which highlighted rising inequity and high levels of deprivation for children, especially those living in families dependent on benefits. These issues are also expected to worsen in the future with the economic downturn. There are currently large disparities in child health status, ‘with Māori and Pacific children and those living in more deprived areas experiencing a disproportionate burden of morbidity and mortality’ (Children’s Social Health Monitor, 2011, p. 7). So do these point to an answer to the question of whether Aotearoa New Zealand is a good place to raise children? And does this question need to be qualified by, and depend upon, resiliency and the cultural, social and economic setting in which the child grows up?

Receiving Aotearoa New Zealand citizenship can be an important day in some children’s lives.

On the positive side, Aotearoa New Zealand is a ‘wonder filled’ country of great natural wealth. Generally, it is well resourced and it benefits from magnificent natural environments – albeit environments under stress from factors as varied as the exploitation of natural and agricultural resources, pollution, rising CO2 emissions, pest invasions, offshore oil exploration and rising levels of traffic. However, for most New Zealanders, to some extent, regardless of social class and income level, the possibility of raising a family in a single-storey detached house with a garden, of having holidays at the beach, of going fishing in rivers or lakes, picnics in parks and of walking in mountains and forest still exists. It is this possibility that is immensely valued by returnee New Zealanders, who want to raise their children here; but in reality ‘growing up’ is more than this. It is equally about the life chances that children experience, including the life opportunities offered. It is about Aotearoa New Zealand’s commitment to ensuring equitable access to these opportunities and to providing children with the nurturing, social, economic, educational, and environmental resources that they need to fulfil their potential. As we will demonstrate, in this regard, Aotearoa New Zealand falls well short of the ideal.

A different and changing country – global children

Situated in the south-western Pacific Ocean, Aotearoa New Zealand’s land mass is 268,021km2. It is a small country by international standards, but in spite of its geographic location far from the global centres of Europe, the US and Asia, it is closely connected to them and affected by what occurs there. The global economic downturn, for example, has impacted on the job prospects and the take-home pay of Aotearoa New Zealand families; yet in a double-edged twist, the 2010 and 2011 earthquakes, which caused human, housing, infrastructural, and commercial disasters in Christchurch, have offset the downturn in Aotearoa New Zealand because of the investment, albeit slower than expected, that is now beginning with Christchurch’s rebuild.

Children live in a globally connected world, and Aotearoa New Zealand’s children are competing on the global stage. This was demonstrated in 2012 by a group of children from Awakeri School, a primary school near Whakatane, who beat teams from Australia, Canada, Scotland, South Africa and the United States to win the World Kids’ Literature Quiz competition. On a daily basis, children at schools around Aotearoa New Zealand join the online Mathletics site, where they meet and compete against children from different cultures from around the world.

Ethnic and cultural diversity is also encountered here in Aotearoa New Zealand, where 24% of children identify as Māori, 11% as Pacific peoples and 7% as Asian, with children being ethnically more diverse than their parents and also more likely to have been born here (Statistics New Zealand, 2002). Particularly relevant is the move towards a more multicultural society, as indicated by the increasing percentage figures for diverse population groups. The six largest Asian groups between 2001 and 2006 recorded the following growth rates: Chinese 40.5%, Indian 68%, Korean 61.8%, Filipino/a 52.7%, Sri Lankan 18.8%, and Cambodian 31.3%. These figures point clearly toward a more diverse population in the future (Statistics New Zealand, 2006).

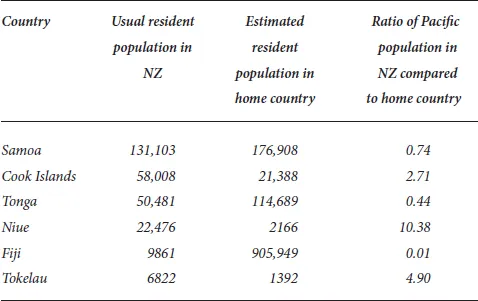

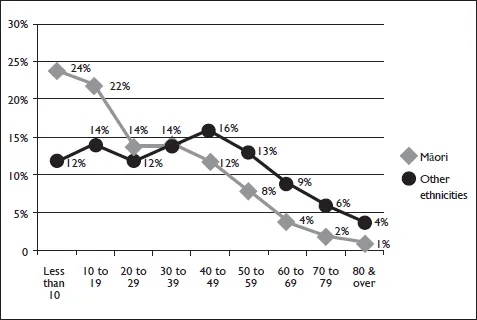

Despite its colonial heritage as part of the British Empire and Commonwealth, Aotearoa New Zealand is a Pacific country in location and increasingly in orientation, with its majority population looking increasingly towards the Pacific rather than Britain for its identity. Indeed Auckland is commonly described as the Pacific’s first city given its large Pasifika population (approximately 178,000 in 2006). For several Pacific groups, more people live in Aotearoa New Zealand than the ‘home country’ (see Table 1.1). The population make-up is important because there is a younger demographic for Pacific and Māori residents (Figure 1.1), who have higher fertility rates than the general population: this results in more families and children, and a higher rate of population increase when compared to other ethnicities in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Auckland is Aotearoa New Zealand’s most diverse city, with 40% of its population having been born overseas and China the most common birthplace. It is home to people from 188 different ethnicities (Auckland Council, 2010), one-third of whom speak more than one language, with Samoan the second most commonly spoken language after English. Generally this diversity is seen positively: half of Auckland city residents (49.3%) believe greater cultural diversity makes Aotearoa New Zealand a better place to live. Moreover, the majority of residents believe that different cultures are valued and respected, and that new people who move to the city are made to feel welcome (p. 74).

Table 1.1: Size of main Pacific ethnic groups in Aotearoa New Zealand compared to home country 2006

Source: http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/pacific_peoples/pacific-progress-demography/population-growth.aspx

Figure 1.1: Proportion of Māori population and of non-Māori population by age, 2006 NZ Census

While Aotearoa New Zealand is increasingly multicultural, with a large Pasifika population and identity, the country’s biculturalism is of particular importance. The bicultural mandate for Aotearoa New Zealand was set down in the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. The Treaty, signed by representatives of the Crown and some 500 Māori from around Aotearoa New Zealand, was an ‘agreement in which Māori gave the Crown rights to govern and to develop British settlement, wh...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword / Keith Ballard

- Part One: The context

- Part Two: Experiencing diverse childhoods

- Part Three: Children’s and young people’s voices

- About the contributors

- References

- Index

- Back Cover